|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Dec 4, 2008 11:49:47 GMT -5

Thread Orientation: Here we can explore these related but distinct topics and picture these things once and for all

_________________________________ Exploring

Sumerian Archaic Standards and Divine Emblems [/color][/size][/center] (..and Cult symbols and Divine Symbols..)

____________________________ So this is another one of those topics which I am in the process of reading about and at the top of this thread am uncertain on, but at the bottom of this thread should have it all but figured out. I think! I am particularly moved to explore this topic after conversing with Rose about comparisons with the Egyptian context, and after her nice offers to check the Leipzig library for helpful materials. First I will attempt to briefly introduce both topics, Sumerian standards and divine emblems, and later Cult symbols. I will also try and mention some scholarship on both, what the distinction between a simple cult symbol and standard is, and hopefully a little of their appearance and function. I think it would be good to start with with standards.. So what are Sumerian standards?

For the below information I am *very* thankful for the article

"Archaic Sumerian Standards"

by Krystyna Szarzyriska (1996)

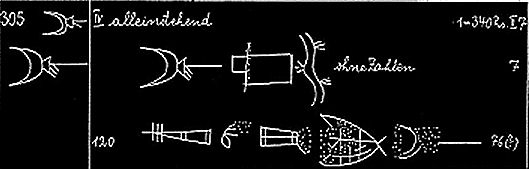

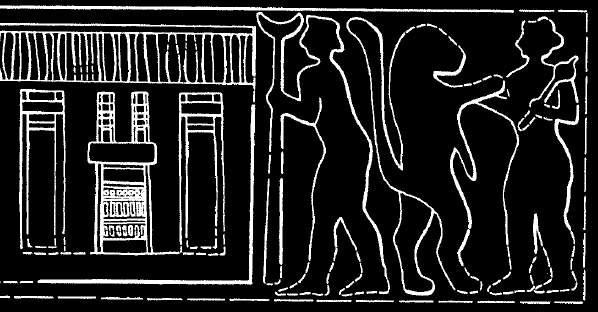

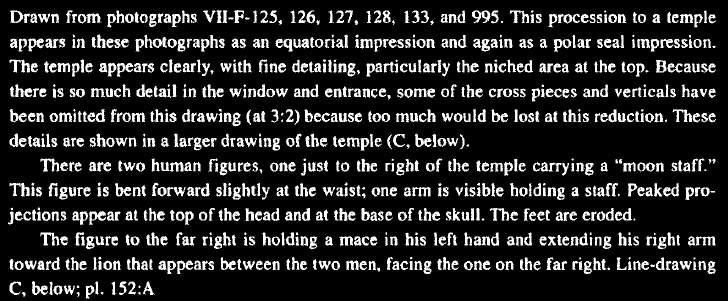

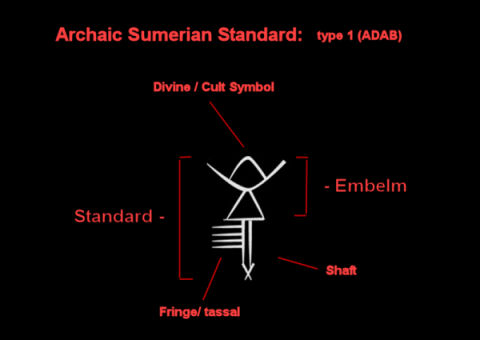

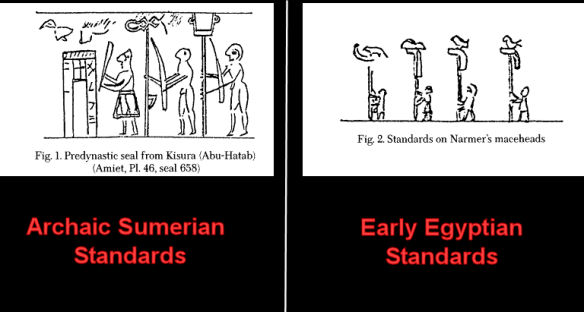

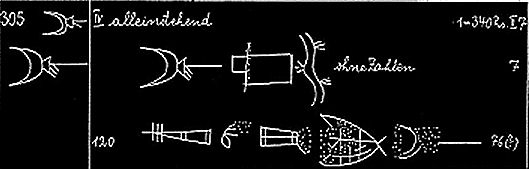

Szarzyriska has in her article provided the above visuals, the Sumerian on the left is from a pre-dynastic seal from Kisura, and depicts "a priest and two nude men [bearing] standards." On the right, the author has also given an Egyptian example of standards from Narmer's reign, for comparative purposes (Sheshki has recently pointed out to me that standards can be observed on the back of the Narmer pallette as well.) Date and Provenance/ Szarzyriska writes there were two periods in which the materials demonstrate the use of standards, there are the early standards (which I am most interested in here) from the Uruk period, and also there is ample attestation of standards of the same construction on Neo-Assyrian reliefs. The examples from the Uruk period are largely from Uruk itself, with the exceptions of standards IV (Ur and Uruk), VI (Ur, Jemdat Nase and Uruk), VII (Jemdat Nasr and Uruk), VIII (Kisura, see above) and X (Ur). Because scholarship has largely focused on the Uruk examples, VII, VIII, XI and X are mostly unexamined in my sources. Function of the standards/ The importance of the depiction from Kisura above, is that it proves that the standards were not just decorative device's or symbols used on the seals to represent some abstract concept - but because the scene clearly shows the standards as physical objects being carried, we know they were "real objects used by the Sumerians in ancient rituals and official ceremonies." So the author believes that they were used in ritual processions and the like, and, in addition some of my initial reading is suggesting they were also carried on the battlefield, and in boats traveling down the river perhaps representing divine journeys. (Mesopotamian before History, P. Charvat.) More to come on that though.. Form of the Standards/ We have to keep in mind here that none of the actual standards have survived to be examined, and so experts are relient on certain depictions in seals, and also Szarzyriska explains, there can be found in the Archaic Sumerian script, in the early writing, signs that were meant to represent several types of standards. She explains: Szarzynska 1996

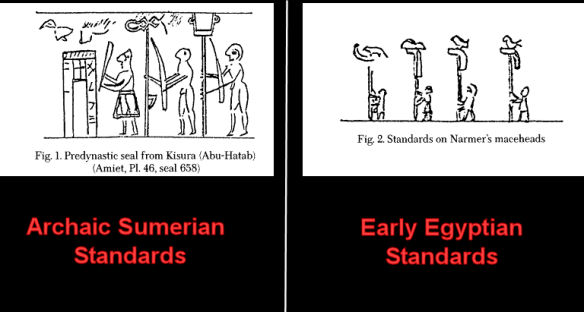

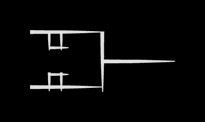

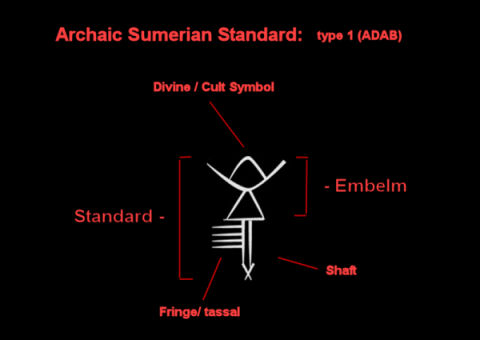

In the archaic Sumerian script, a group of signs representing several types of standards can be distinguished. These signs share the following elements: a) a high shaft made for carrying and, judging by the pointed lower end, for driving into either the ground, special pits, or openings in walls, platforms and pedestals; b) an emblem fastened to the top of the shaft with the aid of a special setting; and c) streamers, fringes, or tassels hanging from the setting, which are most likely in the ends of the band fastening the emblem to the shaft.

[/color]

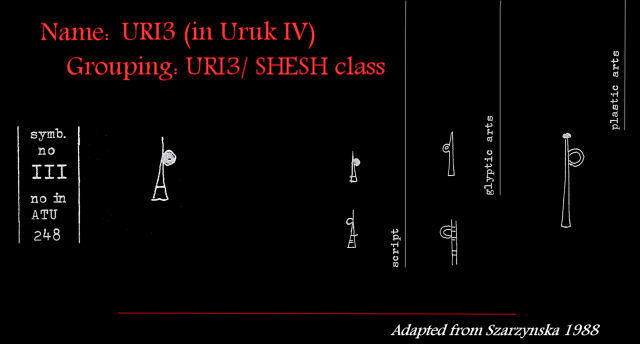

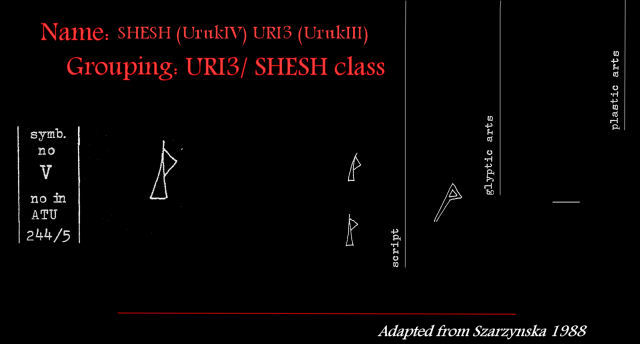

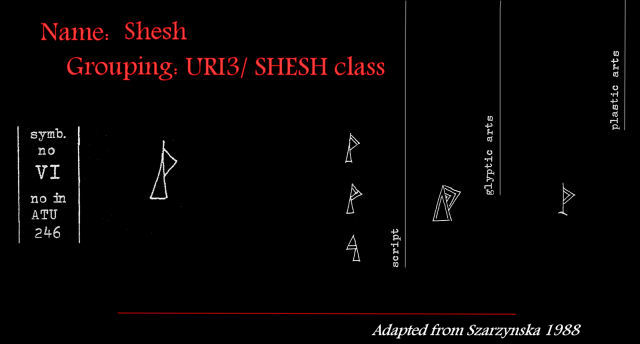

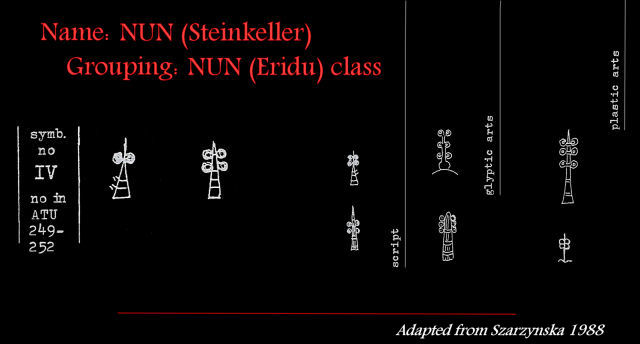

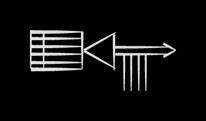

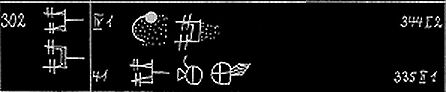

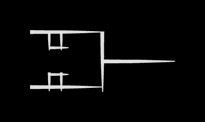

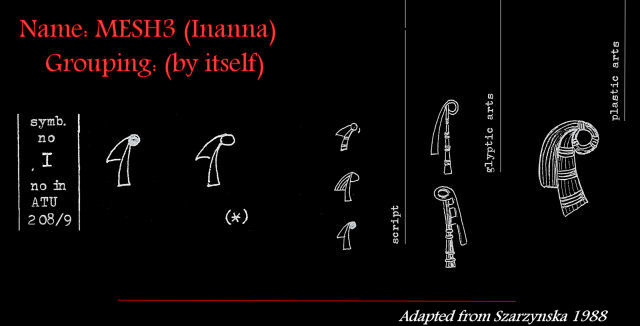

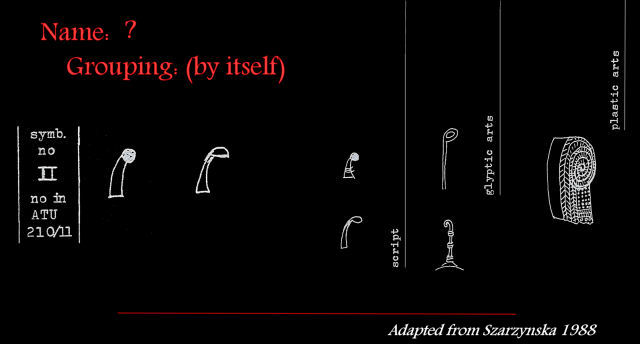

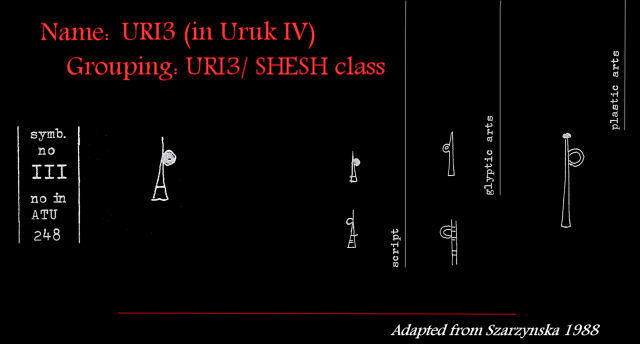

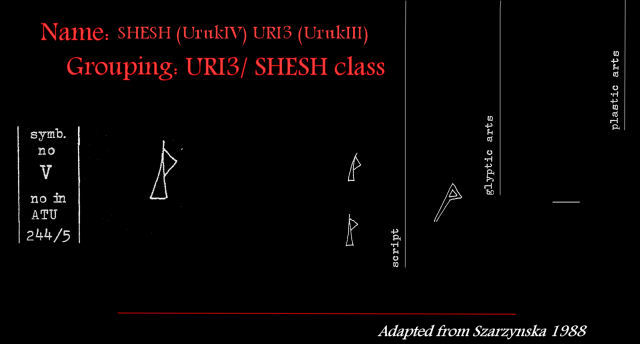

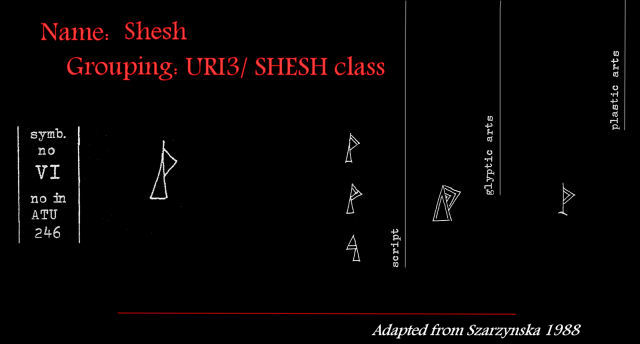

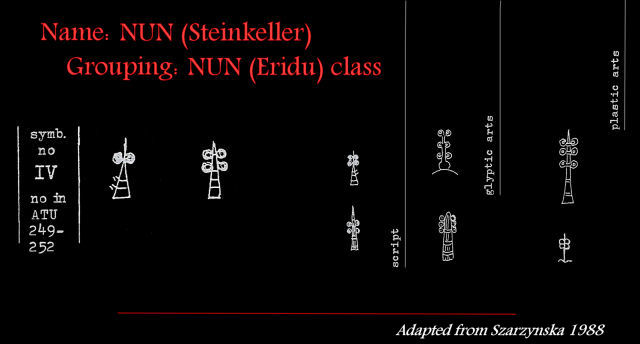

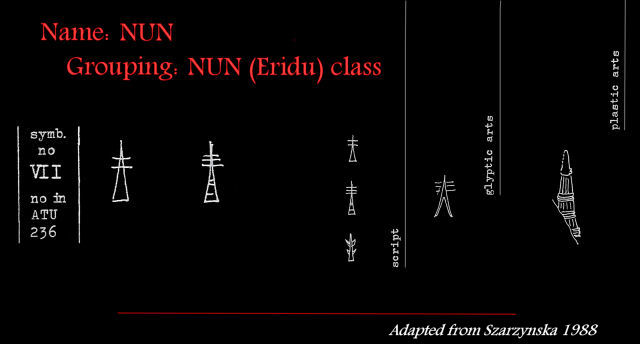

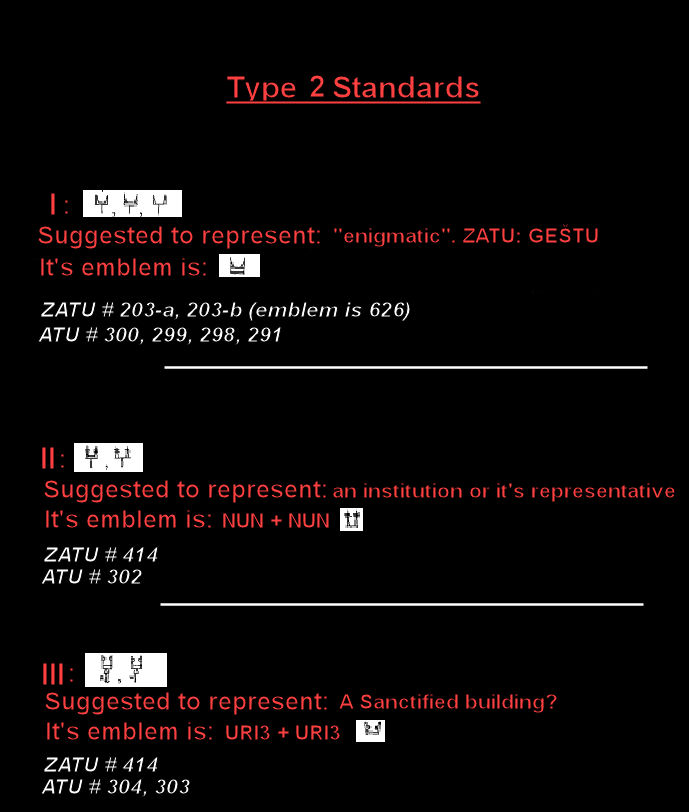

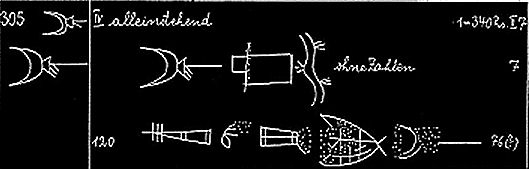

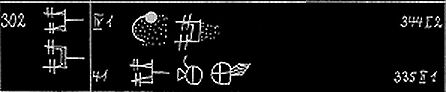

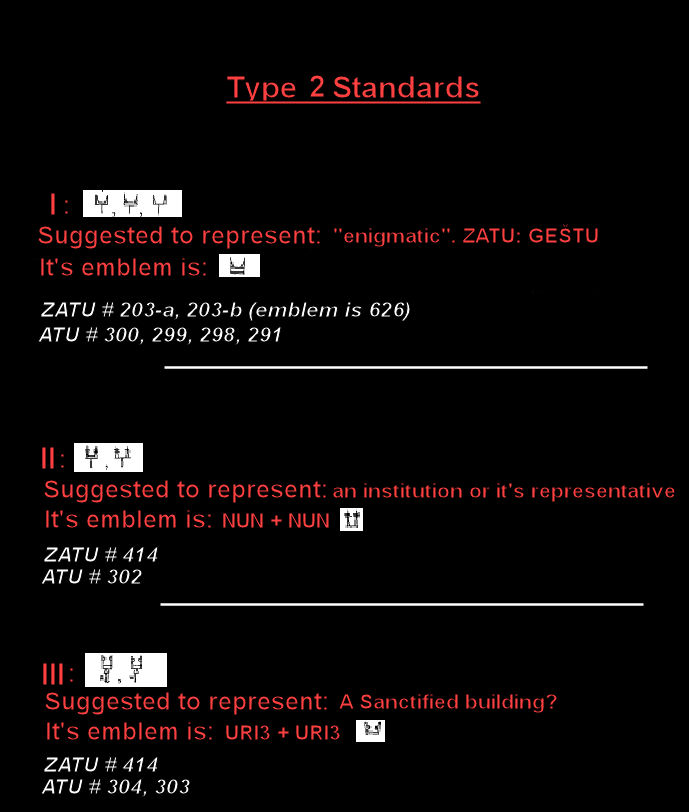

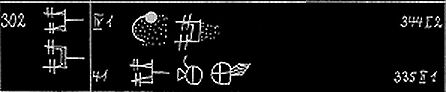

The author distinguishes two main types of standard, of the 10 archaic standards she examines, seven are type 1 and three are type 2. I have decided a visual presentation is the only possible way to communicate this information effectively, and in the below I have closely adapted table 1.1 from the article: Type 1 Standards: The major distinction between these and type 2 standards, are that they contain just one emblem mounted on the pole. Above we see IV contains the ŠEŠ (Nanna) emblem, V contains the U 4 (UTU) emblem, and VI contains the shield/KALAM emblem and so on. Despite that some of these contain emblems that directly invoke the divine, Szarynska states that they do not represent deities themselves, rather the IV is suggested to represent the cult of Nanna in Uruk for example. Type 2 Standards: The author tells us here that the emblems that are affixed to type 2 standards are "affixed in pairs to both ends of a small horizantal support. This second group..is closely connected with the cult symbols placed in pairs on both sides of the gates of buildings and of reed huts." Among the symbols that make up the emblems on these standards are MUŠ, ŠEŠ and URI3, and Szarzynska believes as these stood outside real buildings, that the standards themselves are "representative of real buildings" and so represent specific cult or administrative buildings rather than cities or regions. Standards in Archaic Script/ As it is mentioned above, the standards are preserved in two formats - on the seals and as they represented by signs found notably in the Archaic Sumerian script, that is, in the early pictographic script which preceded the development of standardized cuneiform signs (although these signs were later adapted into cuneiform as well.) I should also explain among the information that Szarzynska provided were the ZATU and ATU numbers for each standard - these abbreviations, ZATU and ATU, refer to special German publications that deal with the Archaic signs. First, those publications are: Volume 1, ATU: Archaische Texte aus Uruk: vol. 1, A. Falkenstein (= ADFU 2, 1926) ( Read it free here) Volume 2, ZATU: M. Green/H. Nissen, Zeichenliste der archaischen Texte aus Uruk (= ADFU 11, 1987) For the below table, Sheshki and I have looked through the Archaic Sign list found at CDLI (link here) and have found these images. When the image is not found at CDLI, we have refered to ATU directly for the below. | | d | d | Standards in Archaic Text | d | d | | d | d | TYPE 1 (note VII, VIII, IX and X not available) | d | d | IV : read "ADAB" |

[/center][/td][td] d[/td][td] V: read "ADAB"(erroneous) [/td][td] d[/td][td] VI: read "KALAM" [/td][/tr] [tr][td]  [/td][td]g[/td][td]  [/td][td] d[/td][td]  [/td][/tr] [tr][td] d[/td][td] d[/td][td] d[/td][td] d[/td][td] d[/td][/tr] [tr][td] d[/td][td] d[/td][td] Type 2 Standards [/td][td] d[/td][td] d[/td][/tr] [tr][td] I: read "GEŠTU"[/td][td] d[/td][td] II: read "NIR" [/td][td] d[/td][td] III : read "NIR" ( erroneous)[/center][/td][/tr] [tr][td]  [/td][td] d[/td][td]  [/td][td] d[/td][td]  [/td][/tr] [/table]

Still to come... Focusing on Cult symbols, reviewing Charvat for more on Standards, closer looks at each standard and its cuneiform, Standards and symbols in the seals etc etc. (note to self: 249/251 is 103 Pritchard) (search for 'SHU.NIR')

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Dec 5, 2008 9:43:39 GMT -5

Whoops. Okay finished it!  Sorry if even read that when half done 0_0 |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 9, 2008 18:52:20 GMT -5

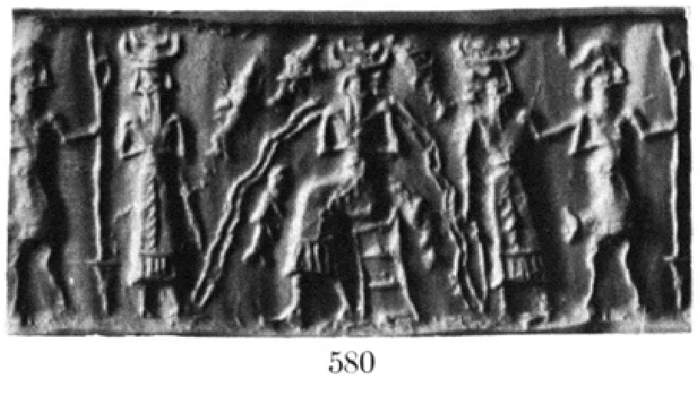

Terracotta plaque showing a bull-man holding a post Old Babylonian, about 2000-1600 BC From Mesopotamia This plaque depicts a creature with the head and torso of a human but the horns, lower body and legs of a bull. Though similar figures are depicted earlier in Iran, they are first seen in Mesopotamian art around 2500 BC, most commonly on cylinder seals, and are associated with the sun-god Shamash. The bull-man was usually shown in profile, with a single visible horn projecting forward. However, here he is depicted in a less common form; his whole body above the waist, shown in frontal view, shows that he was intended to be double-horned. He may be supporting a divine emblem and thus acting as a protective deity. Baked clay plaques like this were mass-produced using moulds in southern Mesopotamia from the second millennium BC. While many show informal scenes and reflect the private face of life, this example clearly has magical or religious significance. British Museum, A guide to the Babylonian and, 3rd ed. (London, British Museum, 1922) J. Black and A. Green, Gods, demons and symbols of -1 (London, The British Museum Press, 1992)  |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Dec 12, 2008 6:02:51 GMT -5

Nice find above Sheshki, yes the bull-man does appear to be carrying a standard, proving that these items did extend to the realm of the mythical as well as to the mundane - its interesting to note the correspondences between this mythical being and that of the priests. Since the standards a cultic or administrative institution, it would be nice to be able to identify the emblem the bull-man holds, though I don't know that is yet possible. Perhaps it pertains to Shamash in someway, though a vase or a flowing vase makes one think of Enki.

__________________________________ šu-nir and urin: The Standard in some Literary Sources

A Sumerian Proverb:

Let the standard that raises itself protect it like the heavens.

/urin\ gal ni2 zig3-ga ḫe2-en-dul? an-am3

__________________________ Small note from "Holiness and Purity in Mesopotamia"/ This is one of the books I ordered from Toronto and am looking through, it is Jan E. Wilson's "word study", that is, the author dedicates most of the book to the study of the occurences of the Sumerian ku3 and the Akkadian ellu. While I will leave an in depth review of the book for an upcoming thread, I will note here just as much as pertains to the look at standards. After flipping through the book, I actually found surprisingly little that pertains to standards or divine emblems - because Wilson goes into some depth in this word study, it can only mean that the standards when mentioned in literature were not directly described with the word ku3, despite that we might still understand them as being holy in some regard. Wilson however, does chance upon one mention of what is possibly a standard when an examination of the text of A prayer to Nanna for Rīm-Sîn is undertaken, the relevant section reads:

The abzu is the august holy shrine of the E-kiš-nu-ĝal, a great vastness in depth and breadth, the foundation of the innermost holy pure buildings, with a pleasant odour like a forest of aromatic cedars and ḫašḫur trees. It forms the foundations (?) of the temple, within the temple, a protection for the temple; the terrifying splendour of the temple, a great corner, a holy corner within the solid interior. The design of the doorway is a magic bond: a solar disc at whose top is a standard representing a rapacious eagle, violently seizing stags which turn to the left and right. Gods stand guard over the doorway.

The section of the prayer to Nanna is absolutely fascinating in itself and contains what the author describes as "the best descriptions of the abzu found in cuneiform literature." Most of us are familiar with the abzu in the context of Eridu, where the term has special connotations and is indeed unique - however this text is evidence to the fact that many temples across Sumer featured an abzu as part of the layout of the temple. Wilson writes that Woolley, who excavated at the temple, found a cistern consisting of 4 compartments on the ziggurat terrace, SE of the ziggurat proper, and this is believed to be the abzu described in this text. Particularly relevant in the text above is the mention of the Standard: "a solar disc at whose top is a standard representing a rapacious eagle, violently seizing stags which turn to the left and right." Solar disc comes from the sumerian word aš-me and standard from urin. While the nature of this standard is not precisely clear, we must assume since it graces the e-kis-nu-gal, that it is infact Nanna`s standard (despite sounding like a combination of Utu and Ningirsu?). If we refer to the visuals I have posted above, we see that Szarzynska has called Standard X "aš-me?" and this is in fact the standard attested only at Ur. Trying the old throw the term in the ETCSL search field "trick"/ One of the things I've been using for a long time is the ETCSL seach field - as simple as it is to type "standard" in there and see what comes up, the information that becomes available even in this simple investigation is, in my opinion, well worth the effort! I have given some selected results below: Standards in the hands of the Divine: a) A hymn to Ḫaia for Rīm-Sîn

21-28. He who fixes the standards on their pegs, planner (?) who artfully excavates (?) the soil of the Land, who decorates the floor and makes the dining-hall attractive for Anšar and the Great Mountain! 21. šu-nir-nir ĝišgag-a du3-du3 saĝ sig9-ga ki galam ḫur kalam-ma b) Inana and Enki

You have brought with you the standard, you have brought with you the quiver, you have brought with you sexual intercourse, 35. [ĝiššu-nir] ba-<e-de6>

c) The building of Ninĝirsu's temple

"fashion for him his beloved standard and write your name on it, and then enter before the warrior who loves gifts," 160. (A6.22) šu-nir ki aĝ2-ni u3-mu-na-dim2

Passages which describe the composition of a standard:

d) The building of Ninĝirsu's temple

He [Gudea] made the metal tops of its standards twinkle as the horns of the holy stags of the abzu. Gudea made the house of Ninĝirsu stand to be marvelled at like the new moon in the skies. 668. (A24.21) urin-bi taraḫ kug abzu-gin7Passages which connect design with deity

[url=http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.2.1.7

]e) The building of Ninĝirsu's temple[/url][/size]

After making a drawing on the …… of the brick mould and …… the excavated earth with majesty, he made the Anzud bird, the standard of his master, glisten there as a banner. 351. (A13.22) anzud2mušen šu-nir lugal-la-na-kamf) 706. Facing the sunrise, where the fates are decided, he erected the standard of Utu, the Bison head, beside others already there 706. (A26.4) šu-nir dutu saĝ-alim-mag) 372-376. There was a levy for him on the clans of Ninĝirsu "Rampant fierce bull which has no opponent" and "White cedars surrounding their master", and he placed Lugal-kur-dub, their magnificent standard, in front of them. 376. (A14.18) šu-nir maḫ-bi lugal-kur-dub2 saĝ-bi-a mu-gubh) 377-381. There was a levy for him on the clan of Nanše "Both river banks and shores rising out of the waters, the huge river, full of water, which spreads its abundance everywhere", and he placed the holy pelican (?), the standard of Nanše, in front of them. 381. (A14.23) u5 kug šu-nir dnanše-kam saĝ-bi-a mu-gubi) 382-385. There was a levy for him on the clans of Inana "The net suspended for catching the beasts of the steppe" and "Choice steeds, famous team, the team beloved by Utu", and he placed the rosette, the standard of Inana, in front of them. 385. (A14.27) aš-me šu-nir dinana-kam saĝ-bi-a mu-gub Summing: Most of the mentions of standards I have selected occur in "The Building of Ningirsu's temple" - this seems to have more relevant content then any other composition. In large part the word šu-nir is used for standards though an example of urin appears above as well ( d). From these lines we learn that the emblems mounted on the poles were metal ( d) and that at least in some cases, the king would have his name inscribed on it ( c). In some cases, the standards seem themselves to have their own names (i.e lugal-kur-dub, g - or was this a king's name? Another thing to note is the number of TYPE I standards mentioned above which consist of the pre-anthropomorphic form of a deity (as with Ningirsu and Nanshe, though it is less clear with the symbol given for Inanna and Utu.) These are like Standard #5 given in the above post. Lastly, the use of the standards is fascinating in the last few examples ( g, h, i) here the standards are clearly relating to their respective clans - Gudea seeks to bring in revenue for the building of the temple, and for each clan, it's divine standard is brought out perhaps to ensure obedience and cooperation. A standard may symbolize a cultic or administrative institution relating to palace or temple, but again with these examples, these TYPE I with divine emblem, a clan with non-secular affiliation. Standards mentioned in two incantations/ TMH 6 9 In Geller's 2003 treatment of Ur III incantations, number 9 is a incantation against Namtar and headache. A standard is mentioned on line 6, the word used is giuri3-e. This means I believe literally an uri3 that is made of reed - this is the ringpost device which we often see at the E-anna temple.. but the word means more broadly 'standard' or this is how it is translated here. Geller 2003 #9

5. In men's bodies is found beer, the south wind blows sag-duru on the (alluvial) land.

In the mountains, the south [wind] blows the scattered seed. He

(the patient) put his trust in the divine standard.

Therefore the gods were afraid, they came down from (lit. in) heaven,

the gods of earth were afraid, and were standing around the grave,

the great gods themselves made (funerary) offerings.

As Geller explains, the mention of beer in men's bodies is meaning actually blood or other fluid - the Namtar demon has by means of the winds disrupted the normal bodily function of the man. The man "puts his trust in the standard" and as we can see, the standard mediates between the divine and the mundane realm, and the belief in its influence and sway with the gods is greatly stressed in this text. They came and made offerings for the man who would die. (It is only later in the text that the advice of Enki would have it's magical effect, reminding us of Inanna's descent, or Atrahasis etc.) CIRPL URN 49: I have come across this very interesting inscription again - it is from Ur-Nanse's diorite plaque, which we have discussed already in the Early Dynastic Incantations thread. It an incantation in praise of the reed, and its function is often given as temple foundation, but interesting to us here is a possible mention of a standard. The only translation I have that interprets a standard on col. iii line 4-5 is that I have recently read in the RIME for the presargonic period which reads:

CIRPL URN 49 (RIME translation)

i 1) O shining reed!

i 2) O reed in the canebrake of the fresh water source!

i 3-4) O reed, you whose branches grow luxuriantly

i 5-ii 2) After the god Enki set you roots in the (post) hole,

ii 3-4) your branches greet the day (or the sun god)

ii 5-6) Your "beard" (is made) of lapis-lazuli

ii 7) O reed that comes forth (from) the shining mountain,

ii 8-9) O reed, may the Earth lords and the Earth princes bow down (before you)

iii 1-3) May the god Enki pronounce a (favorable) omen (for your construction.)

iii 4-5) Its shining renowned standard (?)

iii 6-7) The god Enki cast it (with?) his (magic) loop

iii 8-9) Praise (be to) Ningirsu!

The line iii 4 possibly mentioning a standard reads ŠEŠ(LAK 32).IB k[ù](?)-ge. While Wilson's study seemed to indicate that standards are not designated with the word ku3 (holy), this could be an early exception - and if this were to designate a standard it would fit in wonderfully with the incantation itself. The remainder of the lines on this plaque indicat to us that Ur-Nanshe wants to build a temple, and the opening lines are an incantation which J. S. Cooper describes as "an incantation to ensure the efficacy of reeds used for the construction of the temple." To what extent these reeds were employed in the construction of divine symbols like uri3 (the ringposts which consisted of bent reed) or to standards with pole and mounted emblem is an interesting question in light of this text. |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 12, 2008 18:59:45 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Dec 27, 2008 14:47:42 GMT -5

Further Discussion: P. Charvat

Charvat in his 1993 book Mesopotamia Before History deals with the Archaic Sumerian Standards (which he refers to as "totems") in a fairly briefly, but potentially informative way. In the below I am attempting to preserve his remarks and compare them with the information above, hopefully also making his fairly technical treatment more understandable. Chavat first mentions there are 9 attestable archaic standards, at least 9 that he is commenting on in any case. First he mentions - the ADAB standard, which in the first post of this thread we have numbers as TYPE I, IV. Chavat simply remarks it is "a new moon standard"

- Next he makes an interesting speculation that BU sign, which resembles a snake or cobra? may also be a standard:

Charvat: "possibly also the BU sign (a snake, a cobra? ibid [ZATU] no. 56, p. 181, for the analysis of which see p.138;)

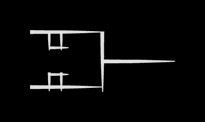

- He comments on what we have above as TYPE II, I - called GESHTU. Here Charvat believes is some sort of connection with the UKKIN Sign, and so the standard has to do with assembly:

Charvat: "GESHTU....this is not desigated as a 'city' but having an UKKIN, or assembly, it is likely to have been a communty; a standard with a pair of horns."

I am not able to fully interpret this remark - as we can see the UKKIN sign represents a spouted vessal which Charvat has in other places explained to be yes, indicatative of an assembly (the vessal having something to do with a custom or tradition at these official's assemblies.) However I don't see on examing GESHTU where an UKKIN is supposed to be or how that factors in at all! It could be taken for a "pair of horns" and Charvat seems to indicate this means it is the standard of "a community" (telling us very little unfortunately.)

- Proceeding to KALAM/UN (TYPE I, VI) Charvat comments: "a standard with an oblong filled in by a grid pattern depicting a textile product?, not denoted as a city but meaning both 'country' and 'people'".

- Next KITI (ZATU 299) is a new sign into our considerations so far which Chavet has given:

Chavet: "a rectangular standard surmounted by the BU snake emblem).

Here Chavet's discussion becomes difficult for me, and I have problems interpreting both the items he refers to, and the implications of his lecture. I will type the rest below as it appears and sort it out as we continue to learn more:

Chavet: "NAGA/EREŠ2/NISABA/UGA (ibid., No. 381, p.250, emblematic value cear from the denotations of the city Ereš and deity Nisaba), NIR (ibid., No. 414, p. 258, a standard with a pair of horns with protrusions, not denoted as 'city' but having an UKKIN and ŠAGAN, probably a delievery point for liquid commodities, see ibid., No. 506, p. 281), NUN/AGARGARA/ERIDU (ibid., No. 421, p.260, again a divine and 'municipal' symbol), UB (ibid., No. 572, p.300, a symbol of a five-rayed star) as well as URI5 (ibid., No. 596, p.306, an AB/EŠ3 shrine with a symbol of the moon god Nannar, see ibid., No. 388, p.252).

Here the signs idtentifying components of the Proto-Elamite corporate entity, perhaps depicting trianglar textile(?) standards with emboridered(?) symbols may be compared (Damerow, Englund and Lamberg-Karlovsky 1989, 16). This kind of symbol, which we would tend to associate with tribal communities, was something that we would have expected in a more prominent position, but this is clearly not the case. In addition to that, some of these symbols clearly refer to local divinities which seem to be summarily identified with - or rather conceived in the form of a supernatural substance constituting the essen of - their shrines, human settlements adjancent to these and perhaps even the surrounding land. KALAM thus means both 'land' and 'people', NAGA/EREŠ2/NISABA/UGA a plant, a city and a divinity, NUN/AGARGARA/ERIDU a divinity, a fish as a typical regional product and a city and the URI3 semantic field constitutes the source of both the notion of the city of Ur (= URI3+AB, read URI5 by the authors of ZATU) and of the local divinity (URI3+NA read NANNA by the authors of ZATU). "

[/center]

Further remarks by the author indicate that it is not possibly to tell overly much by about the communities the standards relate to based on consideration of the standards alone - never the less these symbols represent "the quintessence of the community in question and [to the ancients must have been] worth preserving at any cost. [/li][/ul]

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Feb 27, 2009 17:41:21 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 12:03:33 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 12:21:30 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 12:33:11 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 13:55:14 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 16:34:11 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

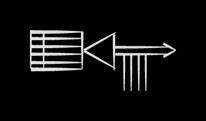

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 17:04:46 GMT -5

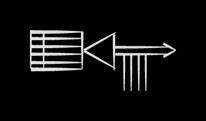

A tablet from Late Uruk, found at CDLI /Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford, containing the KALAM sign.  cdli.ucla.edu/P005157 cdli.ucla.edu/P005157 |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jul 23, 2010 8:44:05 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by madness on Jul 25, 2010 3:58:39 GMT -5

Does anyone have access to Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap Ex Oriente Lux (JEOL) ? Piotr Steinkeller comes through with the goods again and enlightens us to the nature of the archaic emblems with his 1998 article "Inanna's Archaic Symbol," in Written on Clay and Stone: Ancient Near Eastern Studies Presented to Krystyna Szarzyńska on the Occasion of Her 80th Birthday. p. 88: The volute-like symbol of Inanna is one of several reed emblems that are represented in Uruk art.6 Two more of those can be identified with certainty: (1) a pole with a triangle, the so-called "buckled post" or "Bügelschaft", which is identical with the sign ŠEŠ/NANNAx (= ZATU-595), a symbol of Nanna7; and (2) a pole with pairs of rings, the so-called "ringed-pole", which is identical with the sign NUN (ZATU-421), a symbol of Enki.8 We can be certain that the Sumerian word describing such emblems was urin(URI3), a well-documented designation of divine emblems in later periods.9 This identification is assured by the fact that URI3 (= ZATU-523) is a close relative of ŠEŠ/NANNAx. It would appear, therefore, that URI3 was derived from ŠEŠ/NANNAx to serve as a generic designation of such emblems.

6 See Szarzyńska, Cult Symbols [=JEOL 30 (1987-88) 3-21].

7 See ibid, pp. 6-7, 12-13; Steinkeller, BiOr 52 (1995) 705, 709.

8 It appears likely that this symbol represents a tree. Note that in Enki and the World Order 166-167 the urin of Enki set-up in the Abzu is said to be a shade-giving umbrella. It is significant that, elsewhere in the same composition, Enki is likened to a shady mes-tree planted in the Abzu: "the master (Enki) is a mes-tree planted in the Abzu; it towers over the lands; it is a huge dragon standing in Eridu; its shade covers heaven and earth; it is (like) a forest of fruit (bearing) trees stretching over the country" (Enki and the World Order 4-7). A similar image of Enki is found in MDP 14, p. 125 lines 2-13 (a Sargonic incantation), where he is compared to a shady kiškanû-tree growing in the "pure place" (i.e., Abzu): "[the master] grew up in a pure place like a kiškanû-tree; Enki grew up in a pure place like a kiškanû-tree; his flood-waves fill the land(s) with abundance; the shade of his 'place of standing' stretches into the midst of the sea like a lapis diadem; the master is like a kiškanû-tree that the pure place made grow; Enki is like a kiškanû-tree that the pure place made grow".

9 Corresponding to Akk. urinnu. Also urin-gal, Akk. urigallu/*uringallu. See B. Pongratz-Leisten, BaghMitt 23 (1992) 306-308, 318-330; AHw., pp. 1429-1430.The relevant lines, 166-167, from Enki and the World Order: The great emblem (urin) erected in the Abzu, providing protection,

Its shade extending over the whole land and refreshing the peopleThis urin would refer to the NUN object. The sign NUN (Falkenstein, Archaische Texte aus Uruk no. 236)  Looks something like a tree. Variants of this sign have rings instead of bars. Steinkeller differentiates between the urin and the šu-nir. The urin is a kind of totem pole that is permanently erected at a cultic site. The šu-nir however are portable standards. He points out the occurrence of these two terms in the Gudea cylinder: He made the Anzud bird, the standard (šu-nir) of his master,

Glisten there as a banner (urin).Now you've listed on this page the archaic emblems of cities: www.enenuru.net/html/misc/cityseals.htmWhat I would like to know is how you chose the one for Eridu. Legrain lists ( Ur Excavations III, p. 14) #398, 430, 431 for Eridu, which display the pole with branches, i.e. NUN. You appear to have selected from #414 the emblem of Adab instead. See his descriptions on p. 39. Also, he lists "the snake" as of Dêr, I don't see why you put a strange object for that one; and "the spread eagle" as possibly of Shuruppak. |

|

|

|

Post by madness on Jul 26, 2010 4:25:06 GMT -5

Espak also mentions this in his thesis Ancient Near Eastern Gods Enki and Ea, n. 5:

NUN represents a tree or a reed, the word nun meaning "prince" - sign often associated with the deity Enki.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jul 26, 2010 12:41:13 GMT -5

Now you've listed on this page the archaic emblems of cities: www.enenuru.net/html/misc/cityseals.htmWhat I would like to know is how you chose the one for Eridu. Legrain lists ( Ur Excavations III, p. 14) #398, 430, 431 for Eridu, which display the pole with branches, i.e. NUN. You appear to have selected from #414 the emblem of Adab instead. See his descriptions on p. 39. Also, he lists "the snake" as of Dêr, I don't see why you put a strange object for that one; and "the spread eagle" as possibly of Shuruppak. Hey Madness, i think we took the names for the citys from another book, but i forgot which. We have to wait for Bill, he sent me a picture of that list. And on that list the sign for Eridu was the one we have in our list at enenuru.net. But we should exchange it because the NUN sign is more likely and we will also add the citynames for Shuruppak and Dêr. Btw, i think that 414 doesnt has the Adab sign, because Adab is a pole with branches and a sun-symbol (UD.NUN) attached to it. If you compare the sign on 414 with the one to the right , which has a sun symbol ontop you will see what i mean.The pictures 400 and 401 do have Adab signs. |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Aug 6, 2010 15:24:20 GMT -5

Madness: Thanks very much for the Steinkeller quote - I will come home after work tonight and try and comment on the significance of his input here. As for now, I note you are as astute as ever - Yes, the NUN sign as we have it posted at enenuru.net would seem to be a mistake.. though the mistake is not precisely ours alone! I you go to enenuru.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=research&action=display&thread=142 you can see I have taken a portion of a page directly from N. Postgates book, and we see number 1 is called "Eridu?" - Frank and I therefore obtained the impression this was a NUN. However, as you are astute in noticing, Postgame seems to be incorrect (and us by extension) - he says these symbols are from Legrain, and I happen now to check Legrain page, 101 where the same sign there is unmistakably number 414. Checking Legrains explaination of the sign, it is in fact "Adab". Good eye man  We'll need to fix that yes.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Aug 7, 2010 9:58:31 GMT -5

Well, that is, Legrain definitely called it Adab. However, as Frank points out, it catogorization is difficult or possibly even doubtful, and Postgate wants to call it a sign of Eridu but leaves the question mark there - in any case we could at least conclude from this that the sign is problematic and a more certain example of a NUN would better be utilized.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Aug 7, 2010 10:33:12 GMT -5

Reading over Steinkeller's comments, it's interesting to note that his article is from a book honoring Szarzyñska, the same scholar whose work on Standards I found so interesting. I'm fairly certain she makes reference to the relation of Uri3 and the Nanna sign, though I am still puzzled how Uri3 could have arisen out of that sign - on a cultic level, how does that work? This would of course invalidate Jacobsen's explanation that Uri3 was based on the gateposts outside the Storehouses of Inanna. Would it suggest some sort of early cultural influence on Uruk from Ur? Steinkeller's particular assertion that the NUN was not only a "pole" (as is often said) but actually a tree of sorts is interesting, and the texts he mentions which compare Enki to this or that tree are fascinating.. Of course, the Kishkanu was a divine purifier, according to Cunningham it spreads purity by virture of its nature, that is it is a connector of the divine and mundane realms (it is rooted in the lower realms yet its branchs reach up to the heavens). In an early dynastic incantation, as I have noted before, we see praise of a reed which as a divine purifier, is able to speak to Enki as it is rooted in the water table below the surface soil - One wonders therefore if this NUN symbol, supposedly representing a real cultic tree in Eridu, might not have had some sort of similiar or even identical function? The problem would then become finding some sort of text that might inform that theory. P.S. Will try and order JEOL from Toronto soon  |

|

|

|

Post by madness on Aug 8, 2010 2:15:26 GMT -5

> I am still puzzled how Uri3 could have arisen out of that sign <

See Szarzyńska, JCS 48 p. 4, table 2 with columns 3 and 4. Compare them with other signlists from different periods. The two signs are so similar that by the Neo-Assyrian period they became a single sign.

> in any case we could at least conclude from this that the sign is problematic <

See ibid., table 2 with row III at the bottom. This confirms that the sign in question from #414 is UD+NUN (Adab).

|

|

|

|

Post by madness on Sept 26, 2010 2:36:50 GMT -5

I hope that the web page is fixed up some time this year. Another perspective that identifies Enki as a tree god comes from Dilmun. Khaled Al Nashef (1986) "The Deities of Dilmun," in Shaikha Haya Ali Al Khalifa & Michael Rice (eds.), Bahrain through the ages: the ArchaeologyHere Nashef looks at the god of Dilmun, Inzak/Ensag. He identifies this Inzak as the god of the date-palm, since a Bahrain stone bearing an inscription to this god is engraved with a date-palm, which Nashef states "can only be the emblem of the deity"; and secondly because in the Enki and Ninhursag text, the name Ensag is written with the sign SA 6 (= GIŠIMMAR "date-palm"). Inzak is identified in lexical texts as Nabû of Dilmun; and in liturgical texts, Nabû/Enzag is described as "the father who gave birth to Uruzebba." (Uruzebba is the emesal form of Eridu) What is interesting is that Nashef then goes on to equate Inzak with Enki. That is, the pair Enki and Damgalnuna were used in Dilmun to mean Inzak and Meskilak. The reasoning for this comes from a Failaka seal, dedicated to Enki, bearing the same date-palm emblem as on the Inzak stone; and because the Nabu/Enzag mentioned above is the father of Eridu, which we would otherwise recognise as Enki. An article looking at "Date Honey Production in Dilmun" also makes a relevant mention on p. 84. www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/paleo_0153-9345_1990_num_16_1_4520 |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Sept 26, 2010 11:26:40 GMT -5

Madness:

This is wonderful! I have hardly ever seen scholarship on the gods of Dilmun so this really is an interesting find. Your reading and note taking on the subject of tree's is a prolific as ever - should drop me a line and let me know how things are going with studies. New email address is bill.mcgrath@utoronto.ca

P.S. Did you want something from Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap Ex Oriente Lux ? There is a mention of this periodical in your July post, but I don't know if there is a author and article title in particular. I should be able to access it at Robarts library now.

|

|

|

|

Post by madness on Sept 27, 2010 6:20:04 GMT -5

You might find something magical in JEOL 30, pp. 3-21.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Oct 21, 2010 10:31:19 GMT -5

Daniel: I hope you would not object, but I have posted parts of your Al Nashif stuff on Enki and Inzak on the course website discussion board (of course giving credit to "an Australian fried of mine"). Prof. Frayne is a believer in Enki as god of Dilmun and so found the quotes from this book fascinating. Thanks again  P.S. I also owe you (yet again) for bringing to my attention JEOL 30, and the work of Krystyna Szarzyriska found therein - this seems like a truly excellent update to her work on Uruk period standards and symbols! Would be an excellent way to continue this thread.. I have gone to the library and made photocopies but am so obligated by researching papers and maintaining daily readings for classes that its hard to do a summary on the side, I may end up scanning the papers and putting them up on this thread 0_0 |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 4, 2011 13:37:55 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jan 4, 2011 17:05:44 GMT -5

Cool  Let no one every say Sheshki is anything but persistent - to state the obvious hehe. Well so far as standards are concerned I have that new article madness sniffed out by Szarzyriska - Frayne tells me she is in fact the teacher of Steinkeller and apparently they are both Polish (so I know where she is in academia a little more). In any case, this should sort some more things out on standards  Hope to post this week. |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jan 14, 2011 13:00:59 GMT -5

.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jan 14, 2011 21:45:31 GMT -5

____________________________________

- Reading -

Some of the Oldest Cult Symbols in Archaic Uruk

Krystyna Szarzynska. JEOL 30 (87/88)

____________________

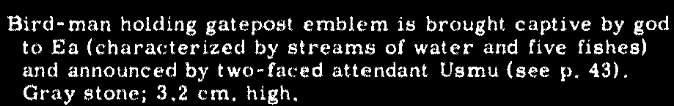

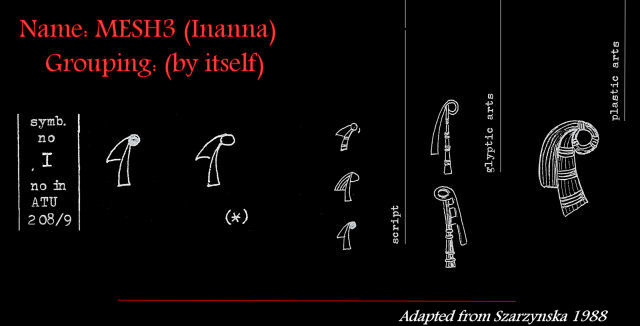

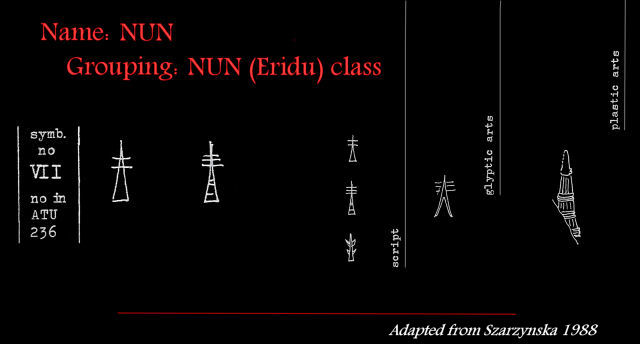

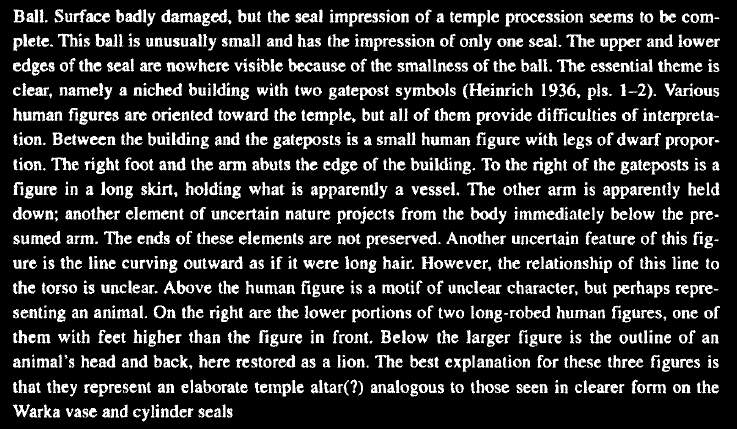

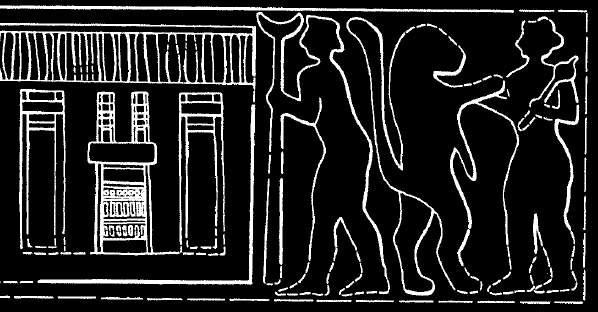

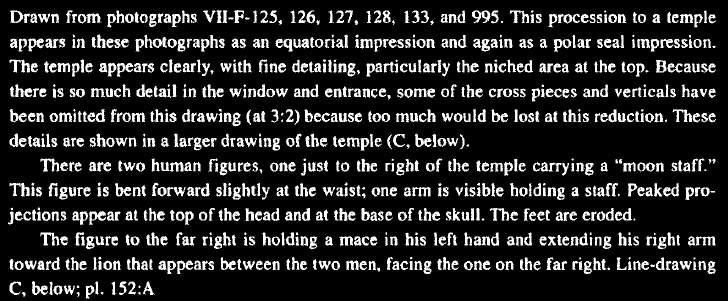

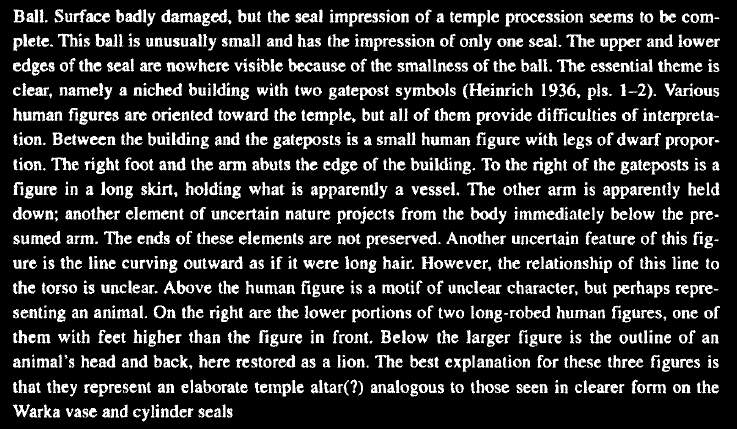

*dedicated to Sheshki on his b-day* Introduction/ Thanks to Madness' continuing attention to this study I have become aware of Szarzynska's 1988 article. As I have recently learned that Steinkeller was the student of Szarzynska (both Polish) it should not be surprising that the work of the former intersects and compliments that of the later. While Szarzynska's article reviewed at the top of this thread is in fact newer, this 1988 article published in Jaarbericht Ex Oriente Lux (JEOL) 30 informs us of the some her earlier and still fundamental understandings concerning the archaic standards and cult symbols. So what are these symbols and what is their relation to the standards? Madness has took an important note from Steinkeller above: "Steinkeller differentiates between the urin and the šu-nir. The urin is a kind of totem pole that is permanently erected at a cultic site. The šu-nir however are portable standards. He points out the occurrence of these two terms in the Gudea cylinder: He made the Anzud bird, the standard (šu-nir) of his master, Glisten there as a banner (urin)." It is likely that the sort of items we are dealing with are the urin type which are fixed totems and this is distinct from the šu-nir, the standards which are the main topic of this tread. And yet the two object types have inter-relations, especially in the case of type II standards (see post 1 above) , where the movable standard, the šu-nir, is little more that a pole with two small depictions of urin mounted on it - i.e two NUN symbols or two URI3 symbols. Again, with type II standards we have a movable šu-nir even if it is composed of a pole with two depictions of the stationary urin totem type. In these cases Szarzynska speculates that the standard is representing a building establishment (as urin signs stood outside buildings). So this post is focusing on this: what are the urin signs? Urin signs and Totem/ An ongoing issue is the question of totem in early Sumer. The issue is hinted at by some Sumerologists, of course an issue is that the emergence of the processes of urbanization that led to written history are likely the same processes that obscured and even replaced tribal structures. From an primitive tribal system with totems to organized religion and temple economy.. Thus the record itself is likely only to contain imprints and echos of that earlier order. Jacobsen in his forward to Adams great work "Heartland of cities" makes the following comment about some of Adams material: "Adam's argument that the earliest cities of the Ubaid and Uruk periods, such as Eridu and Uruk, with their astoundingly elaborate and monumental architecture, are best understood economically as "central places" - that is, as centers for pilgrimage to religious festivals and for exchange of goods, and so drawing support widely from both settled and nomadic populations - fits remarkably well with the apparent meaning of the oldest city names. They suggest terms for tribal storehouses of nomadic or seminomadic groups in which the tribe's valuables, especially its religious emblems, were kept." While Jacobsen's work on city names creates a spark or a notion of tribal stucture (see JCS 1967 Some Sumerian City Names, it remains, all and all, unproven at present (in my estimation). Symbols under discussion/ The author treats seven symbols in this discussion which have the following things in common: a) they are all poles topped with various elements - the various ways that these forms are preserved (written or drawn on clay for example) are representations of the original real objects which were "made of high reed stalks bound together..." b) in addition to appearing in the archaic script they all appear in archaic glyptic (on seals) and archaic plastic arts (on sculpture) - except #7 and c) we are dealing with examples from Uruk in the Uruk period. In the following series of images, I have adapted information from two tables the author supplies; I have grouped symbols together based on the identifications she makes throughout the article (to be explained below.) For each symbol (1-7) the variants in form in script, glyptic and plastic art have been provided by Szarzynska: GROUPED BY ITSELF: SIGN I _______________________ GROUPED BY ITSELF: SIGN II _______________________ GROUPED AS URI3/Shesh connection : SIGN III, V, VI _______________________  _______________________  _______________________ GROUPED AS NUN: SIGN IV (STEINKELLER), VII _______________________  _______________________ Dating and distribution of Symbols 1-7[/color]/ Szarzynska: "In texts all the symbols are attested in Uruk, but symbols II, III and IV are restricted to that period. The other symbols (I, V, VI and VII) also occur in later periods and in the whole of Sumer. In glyptic and plastic arts the reed symbols (except nos V and VII) are attested in archaic Uruk, and some of them also in other Sumerian cities (symbol I in Tell Agrab, III in Kisurra, IV in Tutub, III to VII in Ur). Symbol III occurs also in later periods and in the whole of Sumer. Symbols II and IV were also found on seals in northern Mesopotamia (Tell Brak and Shibaniba during the Jemdat Nasr period), but the seals in question could have been imported into that region from Sumer." The author notes that symbols I, V/VI and II sometimes appear together with a divine determinative suggesting they represent deities; further, the association of MUSH3 with Inanna and SHESH with Nanna is known - hence Szarzynska states: "the hypothesis that all reed symbols represented deities (at least during the archaic period and in particular regions) seems possible." However, other than the cases of Inanna and Nanna, such associations are lost. URI3 and NUN remained in use in later times, though with abstract meanings ('protection' and 'noble/princely' respectively.) Discussions on Symbols 1-7/ Symbol I: The pictograph MUSH3 has "always been recognized as a symbol of the goddess Inanna" the author states. Symbol 2: Despite having been identified as a variant of symbol I by some authors (Falkenstein and Heinrich for example), Szarzynska finds reason to argue against this; her biggest objection is that these signs sometimes appear simultaneously in the same text but in "separate entries as independent designations." As the scribes would not use so different signs to designate the same object in the same text, Szarzynska feels symbol II must have a different (yet unknown) meaning. - Further, symbol 2 cannot be identified with symbol 3: the former it one continuous reed stalk rolled at the top, while the latter it straight at the top with an addition looped reed tied onto the side. Therefore the symbol 2 stands alone. Symbol 3, 5 and 6: The author now makes some intriguing distinctions - first, her strong suspicion is that symbol III was in fact the original URI3 sign, in the Uruk 4 period; it's frequent appears in glyptic and plastic arts in a apotropaic function supports this. However, sometime in the Uruk III the symbols for URI3 changed in form to symbol 5 (with a single triangle). Complicating this change, the author says, is the fact that symbol 5 had meant until then, SHESH, in the Uruk 4 period; now, and in order to distinguish the two meanings in the Uruk 3 period, SHESH took on the form of symbol 6 (double triangle) while URI3 occupied the form of symbol 5, the single triangle. The author supplies the following chart by way of explanation. Usages of Symbols 1-7/ The use of Symbols 1-7 on the reed huts of pens/ *See the author's table 6*Szarzynska explains that archaic sources demonstrate how common place it was in the early period for these cult symbols to be placed on the huts of cattle pens and the like. She understands this to indicate the subordination of the pens "to a specific owner, in that period a specific deity or its temple administration. Common pens, whose pictures are found on some cylinder seals, as well as in the script... are not marked by symbols." This arrangement therefore points to a very particular sort of social organization under a temple administration - that these symbols on pens began to disappear in later script indicates to the author the changes occurring in locals cults.. an exception is the NUN over pen sign which she believes continued to be used in the vague sense of 'big pen'. Symbols 1-7 on temples/ *See the author's table 5*Although Szarzynska doesn't say much here, her table is a clear indicator that the urin symbols under discussion served to designate temples themselves - hence the significance of the pen marked by such signs (perhaps by means of the symbol it was designated as under the authority of this or that temple and it's god). In the gallery section of enenuru.net we discussed the Ring post outside temples (see the following write up, lower section ; in that discussion I argued against the idea that the URI3 sign should be limited to Inanna - as we have seen now in Szarzynska's material, that argument is actually redundant as the two "ringposts" are conceptually quite different. Symbols 1-7 as free-standing objects/ *See the author's table 7*a) in cult scenes (table 7 fig. 1, 4, 5, 11, 15, 20, 22) b) as symbols drawn on cult vessels (table 7 fig. 3, 14, 16, 21) c) in the form of small decorative objects (table 7 figs 8, 9, 17) d) placed on alters (table 7 fig. 2, 6, 7) e) as cult emblems in pairs on procession standards (table 7 fig. 12, 13 and 23) Szayzynska notes that in later times, symbol 3 was carried by deities and heros. Again, this is URI3, a sign completely independent of Inanna (symbol 1). Though the author doesn't state this, I would think that this suggests however that symbol 3 and its original meaning were not entirely abandoned in the Uruk 3 period (for this suggest see discussion of symbol III, V, VI above). Steinkeller and the identification of Symbol IV / Szarzynska has left the identification of symbol 4 open, she notes that the symbol appears on the cult vessel from Uruk next to the symbol SHESH of Nanna; that in glyptic, it was drawn on richly decorated temples to which procession boats approach with offerings, and it was placed on big cowpens; its fairly wide distribution suggest "symbol IV was connected with a deity with a relatively wide-spread cult." As Madness notes above, this gaps may have been filled now by the suggestion of her own student, Steinkeller who considers symbol IV as "a pole with pairs of rings, the so-called "ringed-pole", which is identical with the sign NUN (ZATU-421), a symbol of Enki." (His logic here is.. "it appears likely that this symbol represents a tree. Note that in Enki and the World Order 166-167 the urin of Enki set-up in the Abzu is said to be a shade-giving umbrella..." see reply #14 above for details.) Concluding/ With this new information we may refine the ways in which cult symbols and standard are discussed at enenuru: Urin: urin are the archaic reed symbols mainly known from Uruk which likely were once the symbols of deities and which hint at a time when tribal worship using totemic symbols were used; as the historic period approaches these symbols may have been maintained and refocused by the emerging temple administration/economy and a sign of this may be the cattle pens with urin installed on them. šu-nir: the šu-nir, the movable standards, are known in two variant types (see top of this thread); while type 1 seem to represent the cult of one or another deity, i.e. the cult of Nanna in Ur, type 2 standards are better understood after urin are explained as they consist of a pole with 2 urin signs (i.e. two NUN or URI3 signs) ; hence, they are perhaps they are movable standards that could be carried around promoting the authority of a given temple administration. While this sort of religious symbolism may seem obscure in the modern view, it is not beyond comparison: |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 17, 2011 14:17:54 GMT -5

Examples of ringposts and a cultic staff, found at Chogha Mish, located in the susiana plain (Iran) taken from OIP 101Chogha Mish, Volume 1: The First Five Seasons, 1961-1971.oi.uchicago.edu/research/pubs/catalog/oip/oip101.html"The archaeological site of Chogha Mish is located in the Khuzistan Province of Iran (Susiana Plain). It was occupied first beginning about 6800 BC and continuously from the Neolithic up to the Proto-Literate period. Chogha Mish was a regional center during the late Uruk period of Mesopotamia; and is important today for information about the development of writing. At Chogha Mish, evidence begins with an accounting system using clay tokens, over time changing to clay tablets with marks, finally to cuneiform writing system." from archaeology.about.com/od/cterms/g/choghamish.htmPlate 154     |

|

[/td][td]g[/td][td]

[/td][td]g[/td][td] [/td][td]d[/td][td]

[/td][td]d[/td][td] [/td][/tr]

[/td][/tr] [/td][td]d[/td][td]

[/td][td]d[/td][td] [/td][td]d[/td][td]

[/td][td]d[/td][td] [/td][/tr]

[/td][/tr]

[/td][td]g[/td][td]

[/td][td]g[/td][td] [/td][td]d[/td][td]

[/td][td]d[/td][td] [/td][/tr]

[/td][/tr] [/td][td]d[/td][td]

[/td][td]d[/td][td] [/td][td]d[/td][td]

[/td][td]d[/td][td] [/td][/tr]

[/td][/tr]

Sorry if even read that when half done 0_0

Sorry if even read that when half done 0_0