|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 14, 2008 10:35:44 GMT -5

We have to discuss 3 titles, Lugal [Gal-Lu2]  Sumerian for "great man", the Akkadian equivalent is read "šarrum" (king); En [En]  close to priest-lord and Ensi [pa-te-si/ensi2]  conventionally translated as city ruler.. The difference between En and Ensi:Jacobsen in his 'Toward the Image of Tammuz' (1970), p.384 n.71, explains that Ensi[g/k] when attested at all, "seems to denote specifically the ruler of a single major city with it's surrounding lands and villages, whereas both "lord" (En) and "king"(Lugal) imply ruler over a region with more than one important city....the Ensi[g/k] seems to have been originally the leader of the seasonal organization of the townspeople for work on the fields: irrigation, ploughing, and sowing. " The author assigns the meaning of the word as "manager of the arable lands" and comments that it would not be difficult than, to see how the Ensi[g/k] could gain high political influence in Early Dynastic times. Differences between Lugal and En:Jacobsen (1970) writes about (among other things) primitive democracy (pg.138) and explains that the assembly (mirrored in myth by the divine assembly) might in times of crises make certain essential decisions. When there was threat of war or dangers to the community they might elect a Lugal - however, when there were "internal administrative crises- need for organization of large communal undertaking or for checking banditry and lawlessness" the assembly would elect a "lord" (En). That author describes: "The "lord" was chosen for proven administrative abilities (he would normally be the head of a large estate) and charismatic powers, magical ability to make things thrive, was the core of his office." In a JNES article Jacobsen/Kramer touch briefly on the differences between En and Lugal (JNES 12, 179, n.41): "The traditional English rendering [of En] "lord" would be happier if it had preserved overtones of its original meaning "bread-keeper" (Blaford), for the core concept of En is that of the successful economic manager. The term implies authority, but not the authority of ownership, a point on which it differs sharply from bêlum (Sumerian has no term for owner but has to make shift with Lugal and constructions with -t u k u) , and it implies successful economic management: charismatic power to make things thrive and to produce abundance." Lugalship (Nam-Lugal) and Enship (Nam-En) : (Adapted from Fischer 1965) Lugal is the royal title "par excellence", like that known from the Sumerian king-list. Nam-Lugal is the kingship as a form of ruling. Lugal connected with a name is found first in Kiš and Ur (Mebaragesi, Meskalamdug), but the combination of the signs  [Gal+Lu2] is already known in UrukIII-Jemdat-Nasr-Time. Unlike the title Lugal and Ensi, the title En as a ruler title [with political as well as social powers] is only known from Uruk. Enmerkar, Lugalbanda and Gilgameš are called "En of Kulaba" (Kulaba is a city district of Uruk) in the "hymn literature", also Meskianggašer, ancestor of the first dynasty of Uruk, and again Gilgameš [have the same title] in the king-list. The statement of Lugalkingenešdudu (ca. beginning 24th century), "he owns the Enship (Nam-En) of Uruk and the Kingship (Nam-Lugal) of Ur" is a characteristic for the connection of En and Uruk. Only one time, at the reign of Enshekušanna of Uruk (ca end of 25th century) the title "En of Sumer"(En Ki-En-Gi) appears.  Epigraphically En is earlier attested then Lugal. The cuneiform sign is found in texts from UrukIVa, at the time of the archaic Sumerian "high culture". The personal name "The En fills the Kulaba", from archaic Ur, shows the high prestige of the title En outside of Uruk. The title En as a title for a priest was often used in Ur (since Akkadian times). Here it is the high priestess of Nanna, city-god of Ur, who used the title. If the En of Uruk was a ruler with a female city-god, Inanna, the title En would necessarily be opposite in gender to the city-god. The En of Uruk-Kulaba was probably more involved into cultic functions then the Lugal, and so, the figure of the priest displayed in priestly functions on cylinder seals from UrukIV layers is to be identified as the En. Important for Uruk was that the high priest also was the leader of the city, so he had also command over the military forces. The politcal aspect of En only shows up in the stories of Lugalbanda and Gilgameš. In cities like Ur or Girsu (the main city of the state of Lagaš) the Lugal or Ensi didn't unify the highest cultic and worldly functions in one person from the beginning. Under Entemena of Lagaš in Girsu there was a highpriest of the city-god Ningirsu, called Sangu who stood next to the Ensi. But this is a relatively late reference (end of 25th century). *A classic note on the En is in Kramer's the Sumerians pg. 141, which states that while the Sanga was the administrative head of the temple, the En was the spiritual head of the temple who: "..lived in a part of the temple known as the Gipar. The En's, it seems, could be women as well as men, depending upon the sex of the deity to whom their service were dedicated. Thus in Erech's main temple, the Eanna, of which the goddess Inanna became the main deity, the En was a man; the hero's Enmerker and Gilgamesh were originally designated En's though they may also have been kings and were certainly great military leaders. The En of the Ekishnugal in Ur, whose main deity was the moon-god, Nanna, was a woman and usually the daughter of the reigning monarch of Sumer. (We actually have the names of almost all, if not all, the En's of the Ekishnugal from the days of Sargon the Great.) The Merging of En and Lugal:Oppenheim calls the relationship between these two functions "complex" and "ill-defined" and referring back to Jacobsen 1970, pg. 144, its explained thats the distinctions between these roles is in fact sometimes blurred. "The related tendencies of kings and lords [en's] to strengthen their position by ruthlessly suppressing all rivals may be seen as a reason why in the various regions of Mesopotamia, as we find them in the epics, only one ruler, either a "king" or a "lord," is met with. With the regional unification of power in one hand goes a gradual merging of the various functions of the two offices, for all of them were needed for a community to thrive. The general warlike conditions would, in the case of the "lord," stress his powers of maintaining order and expand his police powers to full military scope. The "king" on th other hand, could not well disregard internal administrative and economic problems in his realm and would thus naturally came to assume also the "lord's" responsibilities for fertility and abundant crops. Thus the magic and ritual responsibilities were added to his earlier military and judiciary functions to form the combination so characteristic of later Mesopotamian kingship." Ensi:In rank, Ensi was lower then Lugal and En. Ensi's were called rulers that reigned independently over a city and the surrounding lands, or rulers, that were dependent from another king.This limitation of the title Ensi shows an inscription of Eanatum of Lagaš, who said that he owned "...additionally to the Ensi-ship of Lagaš the kingship of Kiš". The rulers of Umma called themselves Lugal in their inscriptions, but from the view of Lagaš they were called Ensi´s. Further Perspective on En's:Why the En makes such an appearance in Jacobsen's 1970 study "Toward the image of Tammuz" because apparent in referring to his note one page 375, n.32: "The En's basic responsibility is toward fertility and abundance, achieved through the rite of "sacred marriage" in which the En participated as bride or bridegroom of a deity. In cities where the chief deity was a goddess, as in Uruk and Aratta, the En was male (akkadian ēnum) and attained, because of the economic importance of his office, to a position of major political importance as "ruler"." In cities where the chief deity was male, as in Ur, the En was a woman, (Akkadian ēnum or ēntum) and therefore, while important religiously, did not attain a ruler's position. Whether male and politically important as a ruler, or female and only cultically important, the En lived in a building of sacred character, the Giparu. Where the En was male and a ruler that building in time took on the features of an administrative center, a palace (see the epics of "Enmerker and the Lord of Aratta" and of "Enmerker and Ensukeshdanna"). Where the En was female this did not happen (Ur)." In regards the Sacred Marriage, Jacobsen quotes a line from TRS 60: "At the lapis-lazuli door which stands in the Giparu she (Inannak) met the end, at the narrow(?) door of the storehouse which stands in Eannak she me Dumuzid.....The connection between the En and Giparu ["storehouse"] are made clear by the text as a whole, which, dealing with the "sacred marriage" shows it to be a rite celebrating the bringing in of the harvest. It describes first how Inannak, the bride, is decked out for her wedding with freshly harvested date clusters, which represent her jewelry and personal adornments. She then goes to receive her bridegroom, the En, Dumuzid, at the door of the Giparu- this opening of the door for the bridegroom by the bride was the main symbolic act of the Sumerian wedding, see BASOR 102 (1946 15- and has him led into the Giparu, where the bed for the sacred marriage is set up.......Summing up we may say thus that-at least in Uruk- the En lives in the storehouse, the Giparu, because the crops are in the storehouse and the En is the human embodiment of the generative power, Dumuzid or Amaushumgalanak, which produces and informs them." Enheduanna and En-priestesses (and princesses):The Gipar at Ur was uncovered by Woolley and was found to be a self-contained residence with kitchens, ceremonial rooms etc and even a crypt. The was the residence of the En-priestesses and a bedroom was incorporated within the shrine which presumably relates to the Sacred Marriage ritual. J.N Postgate (1992 ph.130) relays: "The earliest En known to us was a daughter of Sargon of Akkad called Enheduana. She is also the most famous, since she is one of the very few authors of a Mesopotamian literary work whose name is known, but she was followed by a long line of important ladies, most if not all of whom were close relatives of the current royal family. Thus among others we find the daughters of Naram-Sin of Akkad, Ur-Bau of Lagaš, Ur-Nammu, $ulgi, (and probably subsequent Ur III kings),Išme-dagan of Isin, and Kudu-mabuk - the last being sister of Warad-Sin and Rim-sin of Larsa. The memory lived on for well over a thousand years, when the last king of Babylon, Nabonidus, in a consciously traditional gesture made his daughter priestess of the moon-god at Ur." |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 14, 2008 17:33:16 GMT -5

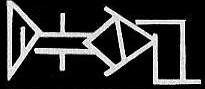

A question comes up which i´d like to adress to amarsin directly. Why is Ensi written pa-te-si but read ensi. And also of interest would be to know why Lugal is written gal-lu2 but read lugal. I know, amarsin, me and my questions...  welcome all new members! |

|

|

|

Post by amarsin on Aug 14, 2008 20:28:42 GMT -5

Well, Sheshki, there are lots of words that are written in unusual ways, just as ensi2 is. For instance, the word sipa, meaning "shepherd" is written with two signs-- the PA sign, and the UDU sign.

Now, of course, since PA can mean something like "stick" and UDU means "sheep" then it's not hard to imagine how a combination of those two can mean shepherd. (Similarly, if English were written in a pictographic script, the combination of man+hammer for "carpenter" is logical, even if there is nothing in the words "man" or "hammer" that sounds anything like "carpenter".)

But while sipa may be easy to make out from its constituent parts PA+UDU, others are less so. The verb e3 is made up of the signs UD+DU. Literally, this combination must mean something like sun/white/bright/shining + to go. But the verb e3 means " to go out" or "to bring in" and it's hard to connect that to the two signs that are used for e3.

In Assyriology, we call these sign groupings "diri signs" after the lexical list that begins SI+A=diri. Words like sipa, ensi2, and e3 all belong to this grouping.

But back to your question, why PA+TE+SI for ensi2? We can surmise that the final -si is a phonetic compliment-- an indicator or prompt to let the reader know how the sign grouping is supposed to be read. As for the PA and TE, I don't know. I'll look more into it and see...

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 14, 2008 21:42:45 GMT -5

hey  great that ur back onboard. the explanation with the carpenter and the man and the hammer was very helpful. e3 is interesting. the signs are the sun and a foot. so it probably meant: to go out where the sun shines or to bring in (from outside where the sun shines)  just had that idea on toilet  |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Aug 15, 2008 10:47:50 GMT -5

I agree. Toilet meanderings = wonderful! Also, Thanks very much for your explanations Amarsin - these are great  If I can, I would like to take your comments and do a little work, and make a SI+A=diri thread on the Sumerologistics board. cheers ;] |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 18, 2008 5:09:22 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 18, 2008 17:39:10 GMT -5

The ascension of the Priests of Ningirsu during the first dynastie of Lagash

quote taken from

Early Mesopotamian Constitutional Development, Nels Bailkey The American Historical Review, Vol. 72, No. 4 (Jul., 1967), pp. 1211-1236

Under Entemena, nephew and second successor of Eannatum and only other militarily strong members of Ur-Nanshes dynastie, the high priests of Ningirsu appeared on inscriptions as coequals with the ensi. The second of these hightpriests,Enetarzi, allowed Entemena´s son (EnanatumII) only some four years of puppet rule before usurping the position of ensi and drawing down the courtain on Ur-Nanshes dynastie.

The next 12 years, during Enetarzi was followed in the office by his son, the high priest Lugalanda, marked the high point at Lagash of the abusive practices that for some time had been eroding the "theocratic socialism" of the temple communities and the remaining clan lands. A reaction ensued (about 2400b.c.) that saw Lugalanda replaced by Urukagina, a man of unknown background, whose efforts to restore the former collectivism and equalitarianism make him the first know social reformer in history. |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 25, 2009 7:18:51 GMT -5

A note about the title GAR.énsi

from the book: Sargonic Insciptions from Adab by Yang Zhi Nin-kisal-si GAR.énsiMe-ba-dur LugalLugal-da-lu LugalBará-hé-i-dùg GAR.énsiMuk-si GAR.énsiÉ-igi-nim-pa-è GAR.énsiIt is tempting to use the titles of rulers as a criterion for dating the Adab rulers, since the writing GAR.énsi looks like an archaism. But the GAR.énsi title in Adab was used consistently from the time of Nin-kisal-si down to that of E-igi-nim-pa-è, who would be closest to the Akkadian era. Elsewhere, the same title was used by Sá-tam, Ruler of Uruk, during early Sargonic times. It therefore seems clear that the GAR.énsi title is not an archaism, but simply a (regional?) pecularity.Concerning the list i have drawn together above, i have not included in it the ruler named Lum-ma, despite the fact that his name is found on two votive inscriptions from Adab (A208 and A 217),one of which describes him as PA.SI.GAR. Lum-ma´s title was written PA.SI.GAR and PA.GAR.TE.SI, instead of the standart GAR.PA.TE.SI of the other Adab rulers; his title was never followed by the qualification "of Adab". These data would seem to indicate that Lum-ma was not a local ruler of Adab, but a ruler from another city who placed votive vessels in the E-sar temple. |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 20, 2011 17:04:55 GMT -5

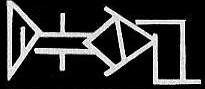

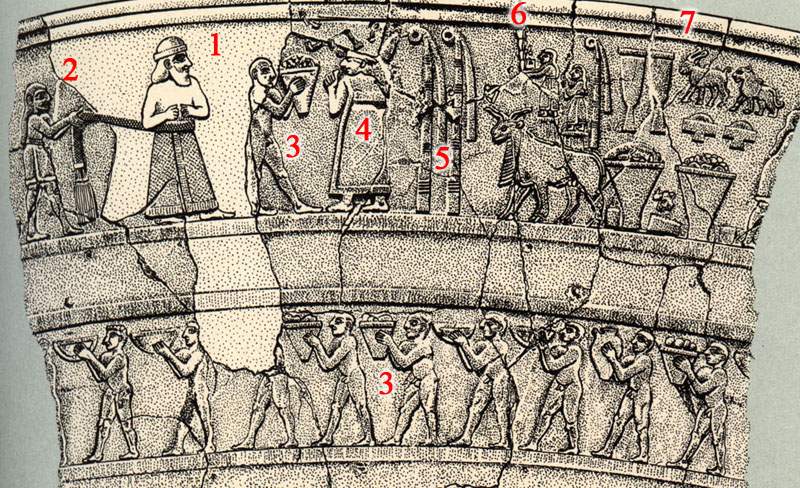

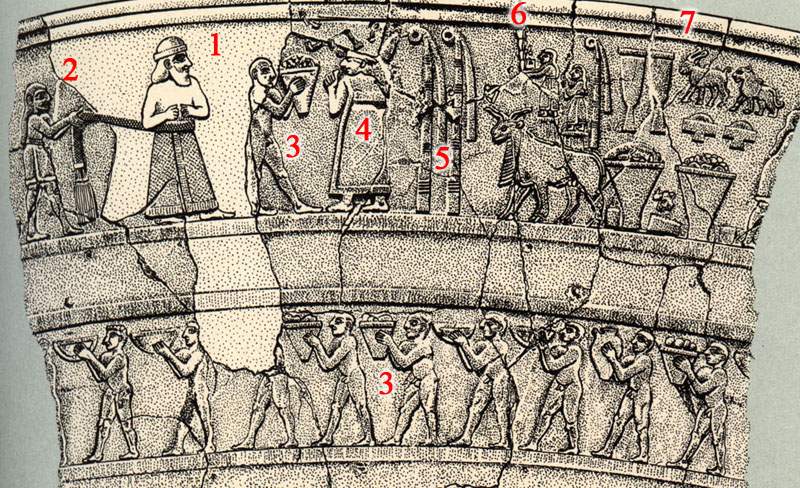

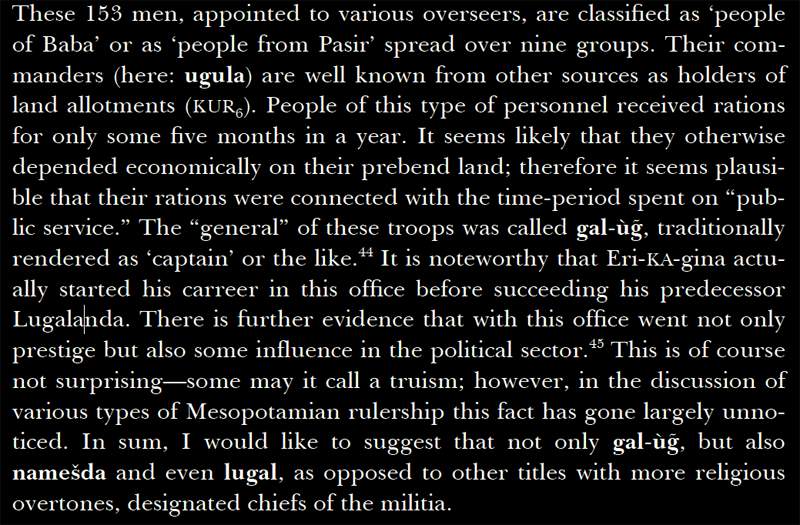

When i first saw the archaic cuneiform sign for EN i wondered what it could have been, an object maybe, or a symbol for a certain type of building.  EN EN EN ENIn "Civilisations of the Ancient Near East"chapter "Theologies, Priests, and Worship in Ancient Mesopotamia"

by F.A.M. Wiggermanni saw a picture of the upper part of the so called "Warka-Vase", plus a description of the scene. This picture gave me a little insight about the object itself the sign developed from. Here is my version of this picture with the description:  Relief bands of a cultic vase from Uruk, late fourth millennium BCE. Presumably at the occasion of a harvest festival, the ruler of Uruk, the EN (1), and his subjects (2,3) bring offerings in form of bread, beer, fruits, and a costly piece of linen to the temple of the citys goddess, Inanna (4), which is marked as such by the presence of her two symbols (gate posts) at the entrance (5). In exchange of the offerings the EN is about to receive confirmation of his office, an object shaped like the cuneiform sign EN (6). Inside the temple (6,7) everything is prepared for a meal to be celebrated by the EN and the goddess (or her human representative) at the end of the festivities, which perhaps included sacred marriage rite. |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jul 21, 2011 18:15:59 GMT -5

from:

The Metamorphosis of Enlil in Early Mesopotamia, Xianhua Wang, 2011

Introduction to the Enlil Project,

0.2.3 "Beiträge zum Pantheon von Nippur"

The author (Such-Gutiérrez) considers that in this period of time, when Enlil seemed to legitimize nam-lugal, "kingship", in northern Sumer, Inanna of Uruk may have held a similar role in the south where the matter of concern was instead nam-en, "rulership". The two traditions in which Enlil legitimizes nam-lugal and Inanna legitimizes nam-en respectively were only integrated in the subsequent EDIIIb period.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 29, 2011 15:51:41 GMT -5

from  "Mesopotamia, The Invention of the City" "Mesopotamia, The Invention of the City" by Gwendolyn Leickp.43 The Uruk period, especially the middle and mature phases, from about 3500 to 3200 BC, is a particularily tantalizing example of how limited our understanding of the past actually is. ..... The highest office on the bureaucratic level at least was accorded to the EN and NIN, the former a male and the latter a female title. The texts suggest that the EN was an apex of a chain of commands, but it is impossible to determine to what extend this was a ceremonial or truly executive function. The parity between the sexes is also a noteworthy characteristic of Uruk society. But the different levels of competence and responsibility the archaic tablets reveal need not be taken as referring to social categories or ´classes` across the whole Uruk society. It is possible that they were primarily administrative categories to begin with, with symbolic or status differences only eventually coming to be associated with privilege and greater power. |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 29, 2011 20:02:36 GMT -5

from  "Mesopotamia, The Invention of the City" "Mesopotamia, The Invention of the City" by Gwendolyn LeickChapter 3 Shuruppak/The Adminiatration of Shuruppak and the ´Hexapolis of Sumer`p.62 Shuruppak lasted for only about a thousand years, roughly the whole of the third millennium BC. It lay in the middle of southern Mesopotamia, half-way between Uruk and Nippur, on the Euphrates near the head of the four watercourses. During the Uruk period there had been some villages and a small town in the area, and the city of Shuruppak emerged in the Early Dynastic period I (ED I 3000-2750), growing fairly rapidly until the end of the Early Dynastic III (ED III 2600-2350), when it covered some 100 hektares. This was the phase terminated by the great fire and the one that was most productive from achaeological point of view. Later levels are badly eroded, but it seems it was an important city in the UR III period (up to 2000)-the city walls date from this time-but fell into terminal decline after the disintegration of the Ur empire. p.77 The administrative tablets give us a good idea of the meticulous organization of the centre, with its clear boundaries of competence and bureaucratic responsibility. There were numerous managerial units, composed of between 20 and 100 employees, supervised by officials called ugula and nimgir. These were in turn subject to control by a head of department. At the apex of the system was the person who occupied the highest political office, called the ensi. |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 1, 2012 16:58:32 GMT -5

from  "Mesopotamia, The Invention of the City" "Mesopotamia, The Invention of the City" by Gwendolyn LeickChapter 4 Akkad/Lugal and the Rise of Kingshipp.89-92 The discussion of titles and nomenclature of offices is notoriously difficult, especially since there may over time have been regional differences as well as changes in meaning. In the Uruk period the highest office seems to have been occupied by one person who alone had the right to the title en. According to Charvát´s analysis, even the highest office of the Uruk hierarchy was part of the `civil service´, though the names of people holding the en post were not recorded, nor were there any signs of ostentatious display or accumulation of wealth. During the Fara period, the en office appears to have shifted to the religious sphere; an analysis of the economic texts suggests that the main duties of the en at this time were connected with the cult, especially in fertility rituals. In the later literary traditions of the Old Babylonian period, a person became en by `marrying`the goddess Inanna. This concept of legitimizing control through divine consent became an important factor in the ideology of Mesopotamian rulership. It seems to have been widespread during the Early Dynastic period. At the same time the lugal (the signs mean something like ´head man´, ´boss´) became more important. During the Uruk age it denoted some overseer of personnel, clearly subordinate to the en. At the end of the Uruk period, especially at Ur, he seems to have assumed greater responsibilities and become a spiritual and secular leader. The rise of individual partriarchal households, the accumulation of capital in the form of productive land and specialized craft production and the increasing secularization of political power faciliated the rise of individual leaders. The rivalry between city states and the vulnerability to attack from outside raiders made investment in armaments and military training imperative. The lugal benefited from conflict and the possibilities of pillage by enlarging his following. He also commanded institutions, and people owed by special allegiance to him, as some personal names show. The primary institution associated with the lugal was the é - usually translated as ´palace´ - the ´household´under the authority of the lugal. The Early Dynastic evidence shows that this office, perhaps first becoming synonymous with direct leadership of the city, arose in archaic Ur, and became an increasingly common form of governing city states. In contrast to the en office, which needed the recognition of the temple and was bestowed on a suitable candidate, the lugal position could be inherited and followed a dynastic succession. He also had the prerogative of controlling systems of measurments and the right to leave written records of his deeds. In other cities we also see some evidence for a two-tiered hierarchy. At Shurppak, for instance, the title held by the local ruler was ensi, who could acknowledge the superior authority of a lugal, who seems to have held sway over a large territory. Rivalries between cities and military engagement, either for defensive or agressive reasons, could well have contributed to an over-arching system of control under the authority of an individual ruler. The greater the territory acknowledging the sovereignty of this ruler, the greater was his power. The sumerian phrase lugal.kalam.ma, "King of all the Land", is thought to denote sovereignty over all of Sumer; it was first used by the kings of Uruk. Lugalzagesi, who started off as ensi of Umma, having conquered most of the Sumerian city states and taken possession of Uruk, called himself ´king of all the lands, king of Uruk, king of the country´. He refers to the ´land´several times in his text, as we have seen before. For the first time, here is a ruler who regards his office as a mandate for a centralized form of government that includes all the city states of Sumer. This vision of a state that comprised the totality of the country as a political unit was new. ... The secularization of power and administration, and the concentration of wealth by families and households, prepared for the individualization of power. The lugal was often a charismatic individual, with personal characteristics and ambitions, rather than a bureaucrat or ´priest´. This does not imply that there was an inherent conflict between ´secular´and ´religious´leadership. More pertinent was the tension between local (city-state) independence and integration into some larger unit (kingdom). While we can to some extent trace an internal Sumerian development of kingship, it is also possible that this form of aristocratic rule originated in a different enviroment from the Sumerian city state. Such a region was the area north of the alluvial plain, where the Tigris and Euphrates come close together. It had a rather different ecological and geographical situation from the southern plains. The slightly sloping terrain prevented the rivers from shifting their courses too much. Michael Mann has suggested that this zone, just north of Kish, was of importance for all Mesopotamia because not only could it support a mixed economy, combining irrigation-based agriculture and herding, but it also commanded a strategic position astride the trade routes to all cardinal directions. He characterizes the region as a ´transitional march´, dominated by competing warlords, usually able fighters who tried to extend their power by raiding and raising tribute for protection. In such circumstances, the leadership is tied to successful military exploits, with the chief´s popularity depending on his ability to secure respect and income. This heterogenous border culture, with its social flexibility, so argues Mann, bred couragous adventurer-kings, quick to seize opportunities for plunder and tribute. Another view suggests that the region was united into a single territorial state, whose gravity point usually remained at Kish, as early as the Early Dynastic period. The title ´king of Kish´suggests a claim to the rulership over a whole region; it appears first in writing with Mesalim (c.2400). However, when this title was borne by southern rulers it may have had a different implication. According to Hans Nissen´s theory, the area around Kish was crucial for the ecological stability of the alluvial plain since it was at this point that the flow of the rivers, relatively close together, could to some degree be manipulated. He proposed that ´from the consolidation of the irrigation system on, it was of decisive importance for the south of the country to be kept under control at this dangerous point... The title "king of Kish" would have been the well earned distinction of the southern Babylonian ruler who carried out this function. Perhaps such a scenario seems to put too much faith in the effectiveness of south Mesopotamian diplomacy; Enshakushanna of Ur, for instance, simply reposts that he destroyed Kish, but it is clear that attempts to unite the north and all the independent city states of the south originate in the area of Kish. |

|

darkl2030

dubĝal (scribes assistent)

Posts: 54

|

Post by darkl2030 on Feb 28, 2012 23:05:29 GMT -5

I can humbly offer a few observations on the difference between these three titles.

As already mentioned above, the oldest of these titles is En and is very likely to have been the title of the archaic ruler of Uruk. This ruler excerised chief political power, and lived in the building known as the gipar, deriving his status from his sacred marriage with the chief goddess Inanna. It is likely that, as was the case from the ED period onwards, other important goddesses of the most ancient Sumerian pantheon were provided with human husbands.

The ensi, in contrast, was a later development that may in large measure may reflect a shift in focus in the Sumerian pantheon from female to male deities. From the ED period onwards, in most of the Sumerian provinces there was a chief political capital and also a more ancient religious capital. The latter of these usually had a goddess as its chief deity and the former a male god who was the son of the older goddeses. Significantly it is this new generation of gods with which the ensis were paired. Examples are Lagash Girsu (Gatumdug and Ningirsu), Zabalam and Umma (Inanna and Shara), Tumal and Nippur, (Ninhursag, later Ninlil, and Enlill), and Kesh and Adab (Ninhursag and Ashgi). The ensi, then, in contrast to the en, functioned as the chief steward or representative on earth of the god of his city. With the ascent of the ensi, the en spouse of the god would be deprived of his political powers and left a religious function alone. Thus we have an early inscription of Ur-Nanshe, Ensi of lagash, commemorating his appointment of the dam, "spouse," of Nanshe.

Reading just a few of the royal inscriptions left by these ensis, it is immediately clear that the chief god, such as Ningirsu or Shara, was a lugal (master) with respect to his ensi and to his city. By virtue of his special relationship with his god, the ensi thereby excercised the function of "lugal" on earth for his god. So the two terms are complementary: ensi describes special relationship between a ruler and god, and lugal simply denoting chief political function. Thus when applied to humans, lugal is free of any religious connotions. But, when the term is used in a context outside of a specific city state, it generally denotes a a hegemonic ruler with a wide territorial claim. After Enlil has replaced Enki as the chief of the pantheon, and had acquired the title "lugal dingir-re-ne," king of the gods, the first empire builders such as Lugalzagesi would claim the title "ensi2-gal En-lil-la2."

The etymology of ensi(k) is totally uncertain, but graphically the two signs for writting it, GIDRU and TE(=akkadian wasaamum) could be potentially analyzed as meaning "the one appropriate of scepter."

The best article on this topic and where you'll find much, much more information on these ideas is Steinkeller 1996, "On Rulers, Priests, and Sacred Marriage: Tracing the Evolution of Early Sumerian Kingship" in the volume "Priests and Officials in the Ancient Near East" ed. by Kazuko Watanabe.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 29, 2012 4:27:55 GMT -5

darkl, thank you for your interesting observations. say, do you know something about the GAR.énsi title mainly used in Adab? It interests me greatly, but it is not easy to find informations about it.

|

|

darkl2030

dubĝal (scribes assistent)

Posts: 54

|

Post by darkl2030 on Mar 5, 2012 20:11:11 GMT -5

I haven't been able to find anything specifically on GAR.énsi, but I doubt that there is any real difference in meaning. What we see is very likely a different scribal tradition or archaism. GAR should perhaps be interpreted as NIG2, which sometimes acts as an abstractive prefix just like NAM, so the writing would have originally signified "Ensi-ship, office of Ensi," but perhaps became frozen at an early date. I will try to remember to ask my teacher and see if I find anything else out.

I did, however recently find out about the most plausible etymology for ensi(k) itself. It may come from en-she-ak, meaning thus "lord of the grain," and was originally the office in charge of maintaining grain collection and storage. There are a number of other archaic professional titles that begin with en, you can check the above mentioned article by Steinkeller for a list of them.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Mar 11, 2012 15:42:40 GMT -5

DarkL : Your post above concerning En, Ensi and Lugal is fascinating - I had yet to really consider Steinkeller's views on these matters, but they seem to really represent a big step forward from, for example, the Jacobsen and Kramer insights seen at the top of the thread. An example of where these views offer an interesting opposition would be Jacobsen's (1970) notion that the the ensi originally had an early role as master or arable lands and then gained political power based on this position; whereas the view you mention (Steinkellers?), that the ensi was the representative of the male gods of political centers, is quite a different point - and yet, Jacobsen's observation of the ensi as master of arable lands may in fact have been a by-product of the role of representive of the chief god. What seems to be most striking about the information presented, I would say, is the view that a shift occurred in Sumerian theology, whereby male deities overtook what may have been at one time the more prominent position of female deities (?). The evidence presented seems to hinge on the mother/son relationship of the deities involved, suggesting that the ancient theologians may have explained the emergence of political centres in the context of the succession of a younger generation; such a dynamic is attestable in the rise of Enlil and in the rise of Marduk certainly. After quickly checking Leick, and an unpublished work of Frayne's, concerning gods and goddesses I will say that Ningirsu certainly was the son of Gatumdug, Shara as I recall is son of Inanna; however, though Ninhursag is the goddess of Tumal, An and Ki or heaven and earth are usually considered to have spawned Enlil; in the Barton Cylinder Ninhursag is the "older sister" of Enlil, as opposed to his mother. Then there is Ashgi of Adab and Ninhursag of Kesh, but do these form a pair in the same way as the others? Ashgi is more specifically the son of Nintu, who some scholars say should be considered a distinct deity from Ninhursag, or at least, distinct up until a point. My concern with the idea of the early prominence of goddesses in Mesopotamia is that the impetus for such interpretations may be the same sort of reactionary (though not necessarily feminist) scholarship that lead to the notions of matriarchy at Catal Hoyuk - a widespread fascination which is now being completely overturned from what I can see (I reviewed Ian Hodder's article at enenuru earlier this year, which found "We suggest that current data do not support the traditional ideas of fertility and matriarchy that have long been associated with discussions of the emergence of settled agricultural life. Rather, current data present a picture of animality and phallic masculinity that downplays female centrality..") So these suggestions are fascinating, but worth careful consideration. |

|

darkl2030

dubĝal (scribes assistent)

Posts: 54

|

Post by darkl2030 on Mar 11, 2012 18:19:34 GMT -5

I should have mentioned originally, actually, that Nippur and Enlil are a special case, because the Enlil was originally a foreign, semitic mountain-deity introduced from the north, and the original chief god of Nippur was actually Ninurta (who later became Enlil's son). I'm planning to make a post sometime soon with some observations about Enlil himself.

Your mention that "Jacobsen's observation of the ensi as master of arable lands may in fact have been a by-product of the role of representive of the chief god" is spot on, because all these younger generation deities Ninurta, Shara, Ningirsu, etc. are essentially agricultural deities (cf. the meaning of Ninurta's name, "lord of the ear of barley).

The picture of the earlier goddess-oriented stage of Mesopotamian religion I mentioned about hardly has anything to do with the now-discounted feminist portrayals of a so-called "matriarchical" society--most especially because the chief deity during this period, and the god with which most of these female deities were paired--was Enki, exactly just such a phallic god of the masculine fertilizing powers of water. ("A" in sumerian = both water and semen).

The other important male god in this earlier period of course, would have been Dumuzi, with whom the en-ruler himself would have been identified in his role in the sacred marriage. Some scholars have even argued that the ruler-figure depicted in Uruk art represents not an En but Dumuzi himself, but once we realize that later Mesopotamian historiography considered Dumuzi to have been an actual king who ruled in distant times, we can see that this these two really are one and the same thing.

Anyway, the whole Gimbutas-derived notion of some sort of prior stage of humanity where mother-goddess worship was central is absolutely absurd since one never encounterers in promordial theology a mother-goddess without an impregnating father-god. Those little fat-lady "Venus" statues that one finds scattered throughout the world in Neolithic times are much more likely to have been magical tokens to help ensure healthy pregnancy than idols of worship. But I digress here.

Anyway, the preponderance of goddesses in the original Sumerian patheon is quite a seperate thing from feminist matriarchical theories. But one last peice of info related to this that I just remembered--the sign DINGIR itself, in Uruk times, was often used to simply mean "Inana," and is in fact originally a depiction of the planet Venus.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Mar 14, 2012 15:15:56 GMT -5

Hey DarkL: Well I have to say you have really hit upon something quite inspiring here with the goddesses in Early Sumerian religion. I was hesitant to acknowledge it at first likely because it's an understanding of the religion I just haven't digested up until this point - However the more you discuss these ideas the more interesting they sound. Steinkeller is pure genius in my opinion and I've found his idea's on the Sun in the Netherworld and this significance of this for divination (Biblica et Orientalia 48, 34-37) to be invaluable when considering the Dream Gods - this totally changed the direction of our years long pondering of the Sisig (See the Sisig Thread Reply number 15) . So I emailed Prof. Frayne about the article of Steinkeller's for his opinion - Frayne is invariably brief in email communications, but always reliable. He states "Steinkeller's article is an important one." 0_0 In any case, in the near future I think we will have to get this article and give it a complete review/ summary here at enenuru - the board must catch up or keep pace with the current discussions of the theology. Thanks for the leads then  |

|

|

|

Post by madness on Mar 15, 2012 17:20:22 GMT -5

> the sign DINGIR itself, in Uruk times, was often used to simply mean "Inana," and is in fact originally a depiction of the planet Venus <

Do you have further information about this?

|

|

darkl2030

dubĝal (scribes assistent)

Posts: 54

|

Post by darkl2030 on Mar 15, 2012 23:57:10 GMT -5

Well, this comes pretty much from the Steinkeller article on city seals, he mentions Jemdet Nasr-era tablets that mention "NI.RU Inana/dingir 3," which he believes refer to offerings for the three forms of Inana (morning, evening, and "princely" (or 'netherworld' if you interpret the sign to be KUR rather than NUN which I believe he told me he does now (I will have to ask again). Anyway, this would be the sole textual evidence for her astral identity as far as I know from this old period.

But as for DINGIR actually being a depiction of Venus, I'm not sure where you would go for that, but you could compare the way venus is depicted in art for pretty much the entire history of Mesopotamia--as an eight pointed star. I'm not sure right now if this depiction is actually found in Uruk art, but this would certainly be worth checking. You can look up "star" in Black and Green too, where they are certain that an eight pointed star refered to Inana/Ishtar/Venus from at least the OB period on, but dont' seem so sure about earlier. But since the writing system was invented in Uruk, Inana was the main deity of Uruk, combined with the abovementioned substitution, I think its pretty assured the "star" of dingir is Venus.

But of course, in Uruk times there was certainly more to Inana than her astral Venus alone--there is yet another Steinkeller article that discusses her volute/standard "reed-post" symbol , which he interprets to be representative of a type of scarf or headband, presumably related on some level to the sacred marriage thing. So she was certainly anthromorphized already then as depicted on the Warka vase, and is very likely to be the one depicted in the famous "Lady of Warka."

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Nov 25, 2012 8:21:33 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Dec 2, 2012 6:12:57 GMT -5

Nice quote Sheshki ;] Yes I wasn't entirely aware of this stuff when some of this thread was going up, but recently reviewed some relevant material for a class. A good discussion of the developments of the Ur III empire, along with nice maps and visuals, occurs in Roaf' s "Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia" in the section dealing with this period. The important innovations were made under Shulgi who expanded the core of the Ur III state -inner Mesopotamia- and who subdued a serious of cities along the periphery, from Susa along the eastern mountain range to Eshnunna. He implemented a bala tax for the interior region and the gun mada (livestock) tax for the periphery region. The interior was put under the control of Shulgi' s governors who were called ensi (a novel use of the word as Michalowski says, though not an entirely different meaning); the periphery was governed by a series of military officials, shagan I think is the word for them.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on May 17, 2015 6:38:07 GMT -5

from Manual of Sumerian grammar and texts by J. Hayes

The different functions of the en and lugal have been much discussed; they varied to some

degree from place to place and from period to period. In Jacobsen's seminal article on "Early

Political Development in Mesopotamia" (1957), he stated that in the earlier periods the en (Akkadian

belu) was more of a cultic figure, while the lugal (Akkadian Šarru) was a war-leader:

In the case of the en the political side of the office is clearly secondary to the cult

function. The en's basic responsibility is toward fertility and abundance.. .The

"king", lugal, in contrast to the en was from the beginning a purely secular political

figure, a "warleader" (1970 [1957] 375 n.32).

Joan Westenholz has expanded upon Jacobsen:

Originally, the title [en] may have referred to a charismatic leader combining the

two functions of spiritual guide and economic manager, with the authority and the

power to make things thrive and to produce abundance, whose cult function was

primary over and above any political power that might have accrued to the office.

With the passage of time, the two functions were separated and the en was limited

to the cultic function (1989:541 ).

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Nov 20, 2015 20:27:25 GMT -5

From: Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia, by Gianni Marchesi and Nicolò Marchetti (2011) The fragmentary geopolitical situation mentioned above (§2.1) is also reflected in the multi-

plicity of terms that were used to indicate the supreme political chief. Depending on time, place,

and political circumstances, the leader of a city-state was called en, “ensi2,” lugal, nun, malkum,

šarrum, or šašhurum. These titles, of course, are not equivalent in meaning: they have dif-

ferent connotations and convey different ideas about the role and functions of the rulers who

bore them.

A first distinction should be made between purely “functional” titles, referring simply to the

exercise of rulership, and titles that had expressly ideological connotations. To the former group

belong malkum and šarrum.

The latter, written with the Sumerogram LUGAL, was presumably the title borne by the

northern Babylonian kings of Akšâk and Kiš, as well as by the sovereigns of Mari. Akkadian

sarrum (later šarrum), “king, sovereign,” is certainly related to Hebrew šar, “chief, overseer,

governor (of a city/province).” It conveys an idea of the ruler as the head of a body of persons

or an organization, the one who leads and gives orders.

This is also the basic meaning of malkum, one of the possible Semitic readings of the Sumer-

ogram EN in the Mesopotamian periphery. At Ebla, the word represented by this logogram is gen-

erally reconstructed as malikum on the basis of the lexical equation nam-en = malikum (ma-li-gú-um),

“kingship, rulership,” in a bilingual vocabulary, and the formula EN Ù/wa MA.LIK.TUM,

which was used in the administrative texts to refer to the royal couple of the Eblaite kingdom,

on the assumption that MA.LIK.TUM is a writing of maliktum. Accordingly, the corresponding

masculine form is reconstructed as malikum. However, there is evidence that the word for “king”

in Pre-Sargonic Ebla was malkum instead of malikum. Moreover, malkum appears not to have

been the proper title of the kings of Ebla but rather a generic term for “sovereign” the use of

which was restricted to the onomasticon. The Eblaite rulers instead styled themselves as šašhurum—

a word that means approximately “noblest one, prince(?)”. It is possible that this title connotes

an idea of the ruler as a sort of primus inter pares.

The term malkum instead derives from the Semitic root MLK, “to have authority, to rule (over), to deliberate.”

The paris pattern, which is preserved in the feminine maliktum, suggests that malkum was originally

an adjective meaning “authoritative, having authority.” Its use as a royal title is allegedly

attested at Tuttul, on the middle Euphrates, and at Beydar, in upper Mesopotamia (on the

somewhat arbitrary assumption that, in the texts from these two centers, EN stands for malkum).

At Mari, in contrast, EN = malkum(?) designates not the king but rather a lesser official.

Whereas malkum means simply “he who has authority (over the others),” the Sumerian title

en, with which it seems to share the same logogram, appears to have been charged with highly

religious overtones. In lexical and bilingual texts dating to the Old Babylonian period or later,

the term en is translated into Akkadian as belu(m), “lord,” or with the loanword enu(m), denoting

either a ruler or a priestly official (usually translated as “high priest(ess)” or “en-priest(ess)”).

However, in the much earlier Vocabulary of Ebla, the abstract nam-en, “en-ship,” is rendered as

malikum, “kingship, rulership,” while en is translated either as ša-ša-hu-LUM, or as šu-šu-hu-

LUM—two glosses that have resisted any attempt at interpretation so far. Chances are, however,

that these glosses represent, respectively, šašhurum and šušhurum ,

that is, šaprus/šuprus variants of later Akkadian šušruhu, “most magnificent, noblest” (with

metathesis of the last two radicals).

In point of fact, Sumerian en does not have the connotation of “master, owner, proprietor” that is proper to Akkadian belum.

The notion of “lord” as master/proprietor is expressed in Sumerian by the term lugal, whereas en expresses the notion of

eminence or very high rank. Thus, for instance, the divine epithet en dimir-re-e-ne certainly

does not mean “the lord (sovereign) of the gods” but rather “the eminent one among the gods,”

that is, “the most eminent of the gods.”

As a royal title, en appears to have been peculiar to the city of Uruk. According to Mesopota-

mian tradition, en kulkullab(a)x(UNUG)ki(-a), “en of Kullab(a),” was the official title of the

early Urukean king Gilgameš (cf. §2.1). This title also appears in the titulary of the legendary

founder of Uruk, Enmerkar, as an alternative or in addition to en unugki-ga, “en of Uruk.” An

earlier occurrence of the title is found in an Early Dynastic literary text from Abu Salabikh, which

is also revealing of the special relationship of the “en of Uruk” with the goddess In`anak and, more

generally, of the function of the en as the one who brings divine favor to his people and procures

fertility and well-being for his land:

en kulkullab(a)x(UNUG) / men sam il2-gen7 / he2-mal2 kalam / ki dar-[ra?] / [. . . ]

As the en of Kullab(a) wears the crown, [she (In`anak) makes] abundance break through the soil

in the Land.

Whereas the kings of Uruk were the only sovereigns explicitly called en in the Early Dynastic

III period, the fact that the word for “king” was written with the sign EN in upper Mesopotamia

and Syria suggests that the use of en as a royal title in earlier phases of the Early Dynastic period

was more widespread. This hypothesis finds support in a passage of another literary text from

Abu Salabikh, which is written in the orthographic style called UD.GAL.NUN:

lu9-galx(NUN) kiši [The kin]g of Kiškiši-ta from Kiš,

lu9-galx(NUN) arab the king of Adab

arab-ta from Adab,

enx(GAL) šuruppag2 šuruppag2-[ta] the en of Šuruppak [from] Šuruppak,

enx(GAL) ennegirx(ENxGI.KI) the en of Ennegir

ennegirx(ENxGI.KI)-ta from Ennegir,

UD enx(GAL)-kix(UNUG) (to) (the god) Enkîk

(the rest is broken) . . .

From the beginning of Early Dynastic IIIb onward, en was considered an obsolete or, in some

way, inadequate political title even at Uruk itself. Indeed, the Early Dynastic IIIb rulers of Uruk

styled themselves lugal unugki, “king of Uruk,” or lugal kiši(ki), “king of Kiš.”

The title “en of Uruk” regained favor in the Neo-Sumerian period and, especially, in the early

Old Babylonian period. It was first assumed by Urnammâk, the founder of the Third Dynasty of

Ur. However, he only made limited use of the title. After his reign, en unugki(-ga) was no

longer employed in the titulary of the kings of Ur. In texts of the Ur III period, the title denotes

the high priest of In`anak, who is also called en din`anakx(MUS3).

It is not until the following dynasty of Isin that en unugki(-ga) was used again in the titulary

of the sovereign: the kings of Isin bore this title in conjunction with, or as an alternative to, such

epithets as “spouse of / dear to / chosen by In`anak,” and the like. The en, it seems, functioned

as a human consort of the goddess. Every year, on New Year’s day, the en was symbolically wed-

ded to In`anak, thus renewing the ties between the goddess and the human community, of which

the en was the highest representative. As Cooper has pointed out, ritual union of this kind—

which is generally referred to as “sacred marriage”—“was a way for the king, and through him the

people, to establish personal and social ties to the gods.” Through the “sacred marriage” the

city-ruler secured “legitimacy and divine blessings” and reaffirmed “his and his people’s obliga-

tions to the gods.”

This reconstruction of the role and function of the en is based mostly on sources from the

Old Babylonian period. However, there are several indications that en-ship functioned this way

already in Early Dynastic times. That the en was conceived of as the human spouse of In`anak at

Uruk, or of other goddesses elsewhere, is suggested by various lines of evidence.

First, in the Pre-Sargonic texts from Lagas, there are scattered references to

an official bearing the title of en. In one text, he is called en kalam-ma,“the en of the Land”—a title from

which we might reasonably infer that there was only one en at a time in the Early Dynastic state

of Lagaš. A few contemporaneous personal names, such as en-dnanše-ki-ám, “The En Is the Beloved

of Nanše,”98 and en-dnanše-mu-du2, “The En—Nanše Created Him,” hint at a special

connection between the en and the goddess Nanše. In this connection, it is worth noting that a

certain type of official of the Nanše cult—who bore the titles šennu (meaning unknown) and

en dnanše, “en of Nanše”—is mentioned in texts from the Ur III period.

In their dedicatory inscriptions, persons who held this office refer to themselves as en ki-am2 dnanše,“the en dear

to Nanše”—an epithet that recalls the Pre-Sargonic PN en-dnanše-ki-am2, “The En Is the Beloved

of Nanše.” Moreover, the “en of Nanše” was the only en in the Ur III province of Lagaš,

just as the en kalam-ma, “the en of the Land,” was the only en in the Pre-Sargonic state of La-

gaš. These parallels suggest that the en or en kalam-ma that we find in Pre-Sargonic texts from

Lagaš was in fact the high priest of the goddess Nanše. In all likelihood, he was also the dam

dnanše, “the spouse of Nanše,” who is mentioned in an inscription of Urnanšêk, the founder of

the First Dynasty of Lagaš. It follows that, already in Early Dynastic times, the en was regarded

as the human consort of the principal female deity of the city-state.

Another piece of evidence is provided by an inscription of Geššagkidug. The long titulary of

this king of Umma includes the phrase en zag kešerx(KEŠ2) dNIN-urax(UR4)-ke4, which

means “the en that NIN-ura tied to herself.”

Finally, there is the famous seal of Mes`anepadda, king of Ur (Pl. 16:2). Curiously, on his

official seal, the king of Ur does not style himself lugal urim5ki, “king of Ur,” but rather lugalkišiki dam nu-gig,

“king of Kiš, spouse of the nugig”—nu-gig being a well-known appellative

of the goddess In`anak, the patron goddess of Uruk. This title probably indicates that Mes`anepadda managed

to ascend the throne of Uruk as well. In this connection, it is worth noting

that in the Early Dynastic IIIb period the rulers of Uruk bore the title “king of Kiš.”

That Uruk was under the control of the kings of the First Dynasty of Ur is also suggested by

a lapis bead found at Mari. This bead is inscribed with a dedication to the sky-god An by

“Mes`anepadda, king of Ur, son of Mes`ugêdug, king of Kiš (i.e., of Uruk).” Since Uruk is the

only cult center of An, the bead in question must have come from An’s temple in Uruk.

After succeeding his father as king of Uruk, Mes`anepadda also assumed the role of en-priest

of In`anak, which was traditionally held by the rulers of Uruk. This role is referred to by the sec-

ond title on his seal, “spouse of the nugig,” that is, spouse of In`anak.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Nov 21, 2015 14:09:09 GMT -5

From: Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia,

by Gianni Marchesi and Nicolò Marchetti (2011)

The remaining terms for “king” or “ruler”—lugal, nun, and “ensi2”—emphasize other as-

pects of Babylonian kingship. The first of these titles, which translates into Akkadian as šarrum,

“king,” or belum, “lord,” has the more precise meaning of “master,” as we can infer from such legal

terms as lugal ašag-ga, “owner of the field,” lugal e2(-a), “proprietor of the house,”

etc., and from the expressions lugal-gu10 and lugal(-a)-ne2 (“my/his master”), which were

used in dedicatory inscriptions, prayers, and letters as forms of address to superiors (gods, kings,

etc.). It is possible that lugal (lit., “big man”) originally designated the head of a household,

as is also the case for nun, “prince, great one” (Akkadian ruba`um/rubûm and rabyum/

rabûm). The latter occurs as a royal title only in the Names and Professions List (a scholarly

composition known from Abu Salabikh and Ebla) with specific reference to the ruler of Kiš.

On the other hand, “ensi2” (Akkadian išši`akkum/iššiyakkum) appears to connote the ruler as a

kind of farm bailiff or steward called to manage the estate of the city-god (the chief deity of the

city-state and head of the local pantheon).

Variously written (NIG2.)PA.SI or (NIG2.)PA.TE.SI, the word “ensi2” (conventional read-

ing) seems to have originally denoted an official who was responsible for superintending agricultural

work. This original meaning appears to have survived in the designation (NIG2.)PA.

TE.SI-gal, “chief steward,” for an official of lower rank than the “ensi2.” The “chief steward”

is attested in connection with construction and maintenance works on canals and other hydrau-

lic structures. Consider, too, that the title PA.TE.SI(-gal) dellilx(EN.E2)/ellil(EN.LIL2)(-la2)

“(chief) steward of Ellil,” was borne by the god Nin`urtâk, the farmer god par excellence.

Both the etymology and the exact reading of (NIG2.)PA.TE.SI are unknown.

The value “ensi2” of the sign complex PA.TE.SI, which is reconstructed on the basis of the spelling u3-mu-

un-si in texts written in the Emesal dialect of Sumerian, is in no way as certain as its wide-

spread usage suggests. There are, in fact, no occurrences of syllabic spellings such as en-si or

en3-si that attest to this reading. Moreover, “ensi2” is usually analyzed as {en-si.ak}; however,

the syllabic spelling ni!(GAG)-in-si in a Sumerian text from Tell Harmal and the Sumerian

loanword išši`akkum/iššiyakkum in Akkadian point instead to an etymon /ninsi`(/y)ak/ or

/nigsi`(/y)ak/.

As a royal title, the term “ensi2” conveyes the idea that the king rules in the name of the city-

god: the former administers the goods and properties of the latter, who, in the final analysis, is

the true master and sovereign of the kingdom. Therefore, “ensi2” is best translated “viceroy.”

However, the ideology according to which the city-god was the true lord and sovereign of the

city-state is also found in places where the ruler normally bore the title of lugal or šarrum, as at

Kiš, for example. In the aforementioned Names and Professions List, the ruler of Kiš is styled nun,

“prince,” while it is the city-god of Kiš, Zababa, who was called “king of Kiš” (lugal kišiki).

Although they have different connotations, the titles “ensi2” and lugal seem to have been

interchangeable to some extent. The earthly ruler was viceroy vis-à-vis the city-god and

sovereign vis-à-vis the population of the city-state. The use of one or the other title may have

depended on the traditions of the individual city-states or on the political or ideological impulse

to emphasize one aspect of kingship above the other. For instance, the rulers of Umma used the

title lugal in their dedicatory inscriptions, but in administrative and legal texts they were referred

to as “ensi2.”

In some cases, however, the ruler of one city-state came under the authority of a hegemonic

ruler of another city-state (cf. §2.1). The fact that the term “ensi2” connoted local control

(“ensi2” being linked to the idea of governing the territory of a city-god on his behalf) resulted in

lugal being chosen as royal title by those rulers who wanted to extend their authority beyond the

borders of their city-states. In this way, lugal eventually became the royal title par excellence.

At the same time, in the period of the Third Dynasty of Ur, “ensi2” came to mean “provincial

governor nominated by the king.”

There is no doubt, however, that in Early Dynastic IIIb Lagaš the title “ensi2” denoted an in-

dependent ruler. Whether or not this was also the case elsewhere is still open to debate. For in-

stance, Edzard was of the opinion that no distinction in rank between “ensi2” and lugal can be

discerned prior to the reigns of Eri`enimgennâk and Lugalzagêsi. According to Cooper, on the

other hand, the term “ensi2” connoted something like “governor, subordinate local ruler,” in its

usage outside Lagaš in Early Dynastic IIIb. Cooper has also suggested that the use of the title

“ensi2” by the independent rulers of Lagaš was in some way a reflex of the past hegemony of Kiš,

just as the use, in later times, of šakkanakkum or išši`/yakkum by the independent rulers of Mari,

Der, Ešnunak, and Aššur harked back to the earlier times when these cities were dominated by

the kings of Akkad or Ur III and were governed by royal officials who bore those titles.

Cooper’s hypothesis is supported by the listing, in the Names and Professions List, of the

“ensi2” after the king (here called nun, “prince”) and before other high-ranking officials.

These officials are mentioned in order as follows: “the (king’s) accountant” (umbisag), “the

land registrar” (SAG.DUN3), “the (king’s) scribe” (dub-sar), “the head of the army” (KIŠ.

NITA), “the chief . . .” (gal-gurx(GU4)-us2), “the en of the Land” (en kalam), “the chief

secretary” (gal-sukkal), and so on. It is likely that this list reflects the bureaucratic hierarchy

of the state of Kiš at the time the list was drawn up and that “ensi2” here denotes an official

who was of lower rank than the king but of higher rank than all other functionaries of the

state.

On the other hand, it is possible that both the rank of “ensi2” and the importance of this title

varied from place to place and from time to time. The rulers of Lagaš applied their own title

“ensi2” to their counterparts in other Sumerian city-states but not to the sovereigns of northern

Babylonia, whom they called lugal instead. In their view, the terms “ensi2” and lugal

were interchangeable only when applied to rulers of southern Babylonia. This fact suggests the

possibility that “ensi2” had a different meaning in the Akkadian-speaking north.

It is equally possible that outside Lagaš “ensi2” was viewed as a lesser title than lugal, indicating

a lower degree of independence or autonomy on the part of those city-rulers who bore this

title. Thus, the alternating use by the rulers of Adab of the titles lugal arabx(ki), “king of Adab,”

and NIG2.PA.TE.SI arabx(ki), “viceroy of Adab,” may point to alternate phases of sovereignty

and vassalage on the part of their city. In addition to the domination of Kiš in Early Dynastic IIIa

(cf. §2.1), there are some indications that Adab fell under Umma’s control around the middle of

Early Dynastic IIIb, before it was also subjugated by Uruk.

Likewise, the assumption of the title PA.TE.SI ummaki, “viceroy of Umma,” by the late Pre-

Sargonic rulers U`u and Lugalzagêsi in the place of lugal HIxDIŠ, “king of. . . ,” which was

borne by their predecessors on the throne of Umma, coincides significantly with the rise of the

Urukean king Enšagkušu`anak as “en of Sumer” (en ki-en-gi) and “sovereign of the Land”

(lugal kalam-ma). It is probably not a coincidence that from the time when Enšagkušu`anak

and his successor Lugalzagêsi sat on the throne of Uruk, no other Sumerian ruler is attested with

the title of “king” (lugal) except in the independent state of Lagaš, where the rulers were traditionally

called “ensi2.” It was presumably in order to emphasize his status as an independent ruler

that the penultimate Pre-Sargonic ruler of Lagaš, Eri`enimgennâk, changed his title from “ensi2”

to lugal in the second year of his reign.

Finally, one last point deserves mention. Even when subordinated to an alien ruler, the Su-

merian city-state remained the domain of its city-god and the appointed “ensi2” was such because

of that god’s will and choice. Two recently published inscriptions demonstrate how the ideology

of the city-state continued to hold strong. ...

Although the city was subjected to either Uruk or Akkad, at the time of Meskigalla, the

true sovereign of Adab was still nominally the city-god (that is, in this specific case, the god

Parag`ellilegarra). Even more telling in this respect is a fragmentary inscription on the statue

of an unknown ruler of Šuruppak, who governed the city under Rimuš...

Though he acknowledges his subjection to the “great king” Rimuš, the “ensi2” of Šuruppak

nevertheless stresses that he holds this position not thanks to the king of Akkad but rather be-

cause he has been chosen by the principal gods of his city. That Šuruppak was now reduced to

a province of the Akkadian empire is purely contingent, an accident of history. The cosmic order

was established once and for all by the supreme god Ellil at the beginning of time. He decreed

that Šuruppak belonged to the goddess Sud, and nobody could alienate her property, not even

the powerful sovereigns of Akkad, despite the fact that they managed to conquer and dominate

all of Babylonia.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 4, 2016 3:20:42 GMT -5

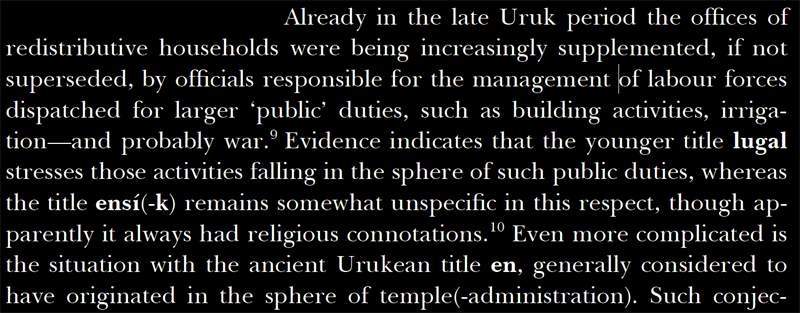

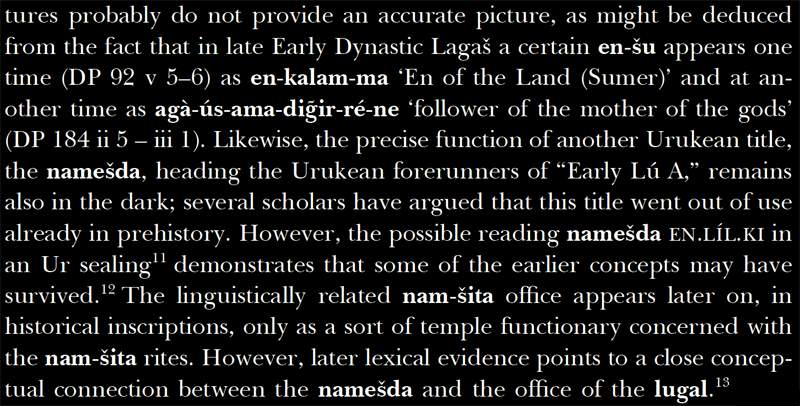

from: City Administration of the Ancient Near East, Proceedings of the 53 e Recontre Assyriologique Internationale Vol.2; "He put in order the accounts...", Remarks on the Early Synastic Background of the Administrative Reorganizations in the Ur III State by G.Selz     |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 4, 2016 13:29:06 GMT -5

from: City Administration of the Ancient Near East, Proceedings of the 53e Recontre Assyriologique Internationale Vol.2; "He put in order the accounts...", Remarks on the Early Synastic Background of the Administrative Reorganizations in the Ur III State by G.Selz  |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 29, 2016 13:20:34 GMT -5

from: The Early History of the Ancient Near East by Hans J. Nissen

Chapter 4/p.94

"Here, however, we must take warning from a few instances in which, although clearly the same title is used in the early period as in the later one, its meaning is obviously different. There are also examples where we have evidence to show that different titles were used for the same office. So, for example, the titles "en-priest" and "lugal" do appear in the early texts, and both can later be used to designate the highest representatives of a city-state or a state, but they appear in isolated cases and in situations where, according to the context, they can only mean a functionary among other functionairs. In addition, in one case they both appear on the same tablet, although they later appear to be mutually exclusive titles."

**As a short sidenote, i bought this book and i´m really trying to read it but man, this guy seems to have "comma diarrhea". Each time i grab the book to read it i´m bored to tears after half a page.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jul 28, 2017 19:05:33 GMT -5

I think NIN should not be forgotten in this thread.

From Altakkadisches Elementarbuch, F. Breyer, 2014

Das Element NIN kommt als erstes Element sowohl bei

weiblichen als auch (seltener) bei männlichen Gottheiten vor.

In der sumerischen Frauensprache Emesal entspricht NIN

bei ersteren gašan, bei letzteren umun,

was eigentlich EN "Herr" entspricht.

Wahrscheinlich war NIN ursprünglich genusneutral und

wurde erst nach Kontakt mit der Genussprache Akkadisch

auf das Femininum eingeschränkt.

|

|

:

:

:

:

If I can, I would like to take your comments and do a little work, and make a SI+A=diri thread on the Sumerologistics board.

If I can, I would like to take your comments and do a little work, and make a SI+A=diri thread on the Sumerologistics board.