Bill,

“seeker: Well, again I will attempt to qualify your suggestions with reference to how the field of Assyriology works, at least in my understanding. An issue with these suggestions is that I think you are starting with the assumption that scholars make alot of arbitrary decisions - "well it could be this, or it could be that...let's choose that!" ; however, in practice good scholarship relies on more than this sort of process. Let me explain:”

Bill, I do not believe that the scholars just choose arbitrary decisions while translating these finds. That’d be foolish to presume that they do so, as it doesn’t make any sense from an academic view. Everything must be checked against all available sources as you illustrate below. I’ll grant you that maybe the way I posited my queries, may have given you this assumption Bill. Of which I’ll be the first to admit I may be hasty at times or that I let poor choice of words feed that assumption. So for now on I’ll create a doc like I did with your reply so I can take my time & formulate a more clear post at home and then post when I can get back online to post it.

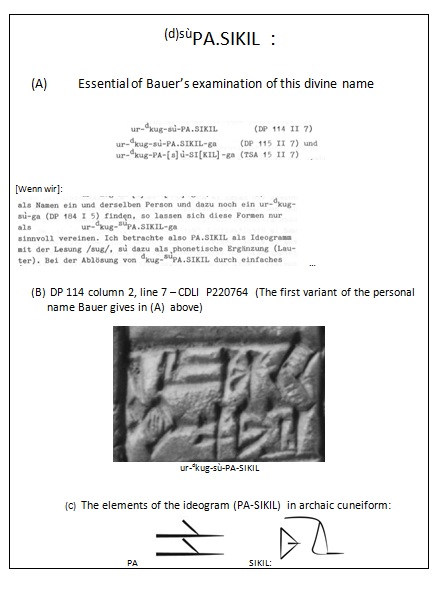

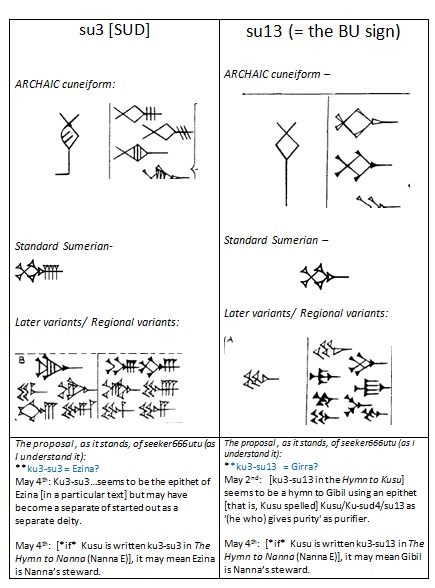

“i) So you see the name Kusu - so we accept ku, but as you notice, the sign su13 (often known as the BU sign) could have other values. In fact: bu, gid kim3, pu, sir, tur, su3-, sud- , dur7, gim7, in addition to su13 and sud4 are possible values. But the point is, scholars do not simply pick a value because it sounds nice - they often rely on ancient bilingual material or lexical material in order to learn the intended value of a name like this. So Mesopotamian scribes composed lists of things, lexical lists, and in the Old Babylonian period and onwards, these lists often had Sumerian one side and Akkadian on the other. By using such resources modern scholars are sometimes able to tease out how a Sumerian word should have been read by reference to the Akkadian and so forth. Or scholars may make reference to variant spellings within a particular corpus of texts. What I am saying is, no one has ever been able to simply 'feel out' how a Sumerian word should be read without this sort of data and these sorts of methodologies, and neither can you or I.”

Signs 01.doc (41.5 KB)

I understand fully the point that the scholars have used multiple sources to come to their conclusions. I’ve read that numerous places, which makes sense for an academic pursuit, especially in archeology. I’m not disputing this at all. But I am concerned with accepting possible mistakes as fact. In point of fact, concerning “but as you notice, the sign su13 (often known as the BU sign) could have other values. In fact: bu, gid kim3, pu, sir, tur, su3-, sud- , dur7, gim7, in addition to su13 and sud4 are possible values.”

You are in part correct (if ETCSL sign list is to be trusted, as I think we both concur it can be), but Su3 & Su13 are only partially derived from Bu. Thus Su3 & Su13 are still derived from different signs.

Here are the valuations from ETCSL:

BU= bu, bur12, dur7, gid2, kim3, pu, sir2, su13, sud4, tur8

SUD= su3, sud, sug4

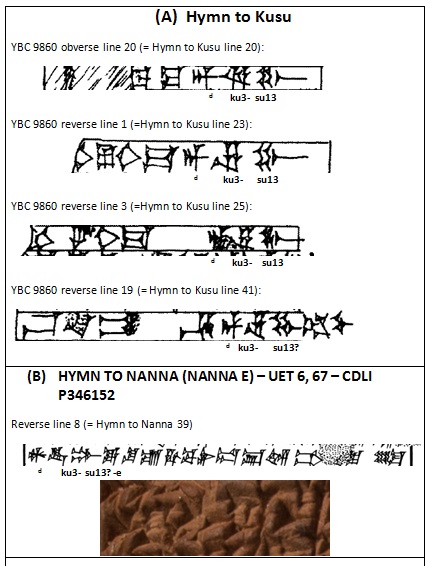

As you can see from the above, Sud, which is the sign from which Su3 is derived, is written with Bu but it is modified with the AŠ2 sign, thus creating a new series of valuations. Does this mean that Kù- Su3 and Kù- Su13 are not variant signs for Kusu? I cannot say, but since Kù- Su3 is the only sign listed in the context for Kusu or Ezina-Kusu in nearly every reference on ETCSL outside of the ‘Hymn to Kusu’ (and possibly the Hymn to Nanna modified by ‘-e’) makes me wonder if they are.

“ii) You might be able to sort of reason 'well nun can actually determine either sex' and 'I sort of want Kusu to be male in order to conform to my early idea' and so on and so on - but this doesn't really establish anything. Again, this is an academic themed forum, and to be academic is at the same time to strive to be convincing. To be convincing in an academic fashion, one must rely on the data not on what we want to see. So to determine that Kusu is female and a 'princess', scholars look to the greater body of evidence, not just in this text, but all the texts that Kusu appears in. They look to the god lists, they look to the fact she has a husband (Indagara) - Sumerian grammar is in fact very gender neutral, but there are times when the gender of a deity is clear, such as when a deity is described as the dumu (son) or dumu-munus (daughter) or so and so, for example. Now I haven't researched the entire corpus of Kusu texts in order to respond to this post, but the point I am trying to make is this: you should not assume that scholars do not have a reason for their treatment of this or that deity, and therefore, a small observation about the grammar of one text can turn everything around. In principal, you should assume the opposite: there are reasons backed by evidence that scholars have treated this of that deity as male or female, reasons that may not be obvious or accessible but exist nonetheless.”

I do understand Bill & I’m not trying to twist this to fit my narrative. I’m just trying to find the truth. If my theory cannot stand under your or others learned scrutiny, then it isn't worth holding.

i. I did not come to my conclusion

by just reading the ‘Hymn to Kusu’, I went through EVERY mention of both Kù- Su3 and Kù- Su13 in the ETCSL noun list before I posited my query & then again as I typed up my initial lost replies (damn ye internet) to your post Bill.

ii. As I said in my previous post I read the hymn in total context both the transliterated & translated forms, thus arriving at my theory…again theory not fact.

Concerning the son/daughter of thing, I mentioned it because ‘Son of the Absu’ is attributed to Gibil, but also in the ‘Hymn of Kusu’ it mentions while exulting him (Gibil), as “great bull of Enki” clearly referring to him in context to the Absu, which if I remember right Girra was also occasional attributed. But as I put forth in my previous posts, I believe since Kusu in almost every other reference in ETCSL

outside of the ‘Hymn to Kusu’, in which Kusu is written Kù- Su3 thus derived from Kug.Bu.AŠ2 not Kug.Bu. That in the case of the ‘Hymn to Kusu’, since Kusu is written as Kug.Bu (Kù- Su13) and if read in full context of the hymn itself, that Kusu (Kù- Su13) is a epithet for Gibil.

Depending on the cuneiform reading in the original ‘Hymn to Nanna’, Nanna’s steward is either written as Kù- Su3-e or Kù- Su13-e, which could mean Kusu the Goddess or if Kusu as an possible epithet of Gibil is Nanna’s steward. Until I see proof on which one is correct, I’ll make no judgment on which Kusu it is referring to. But I will say from the context that the hymn is written Kù- Su13-e may the correct form not Kù- Su3-e, as that was how kusu was written first in the hymn. If that is so, Nanna’s steward is likely Kusu (Kù- Su13-e) derived from Kù- Su13 (Kug.Bu), written in the same manner in which the Kusu of the ‘Hymn to Kusu’ was written, not the Kusu who’s consort is Indagara and frequently mentioned with Ezina or as part of Ezina- Kù- Su3 (Še.tir-Kug.Bu.AŠ2) combined form.

I believe this might be the case because “Kusu establishes the lustration rituals created in their specific house -- the oven for oxen, sheep and bread” (in the Hymn to Nanna) is almost identical

in context, as is found in the ‘Hymn to Kusu’ here: “Kusu has then put numerous bulls and numerous sheep into the great oven. Kusu has then put numerous bulls and numerous loaves into the great oven” and of Gibil himself here: “in the oven and purified by the torch”.

If taken in that context. It would seem that Kusu purifies with heat or fire, be it in ovens or heating oils for sacred use, in which he then uses the oil to wash Nanna, again as inferred in the ‘Hymn to Kusu’ here: “This water consecrates the heavens, it purifies the earth. It purifies the cattle in their pen. It purifies the sheep in their fold. It purifies Utu at the horizon. It purifies Nanna at the zenith of heaven. Thus may it cleanse, may it cleanse the …… of the house.” Kusu is seen cleansing/purifying both Nanna & Utu, among other things in this context.

In all the references on ETCSL I’ve read so far (I don’t have all of them here) never mention Kusu (Kù- Su3) purifying, especially with heat. Does that mean she doesn’t? I have no idea, as I can only draw from ETCSL at this moment. She is often mentioned bestowing compassion with Ezina

here or simply mentioned as either with her consort Indagara

here or combined with Ezina as one being

here,

here,

here &

here.

I think the evidence calls for at least questioning the premise that Kù- Su3 and Kù- Su13 are the same deity & Kusu (Kù- Su3) is not the focus of the ‘Hymn to Kusu’, but Kusu (Kù- Su13) as a possible epithet for Gibil as purifier (and potentially steward of Nanna) Bill. That is all I’m putting forth a theory, based on available ETCSL sources as evidence, nothing more.

“Some further responses:

iii) Yes there is something going on with Ezina-kusu and with Kusu, I have just glanced at the Michalowski article which originally published "Hymn to Kusu" - scholars debate whether there were two separate deities, the grain goddess and Kusu who had a special role in purification and was in charge of the censor. In this hymn, she appears opposite Girra, and the censor and the torch (the title of Michalowski's article) did have special roles in Mesopotamian cultic rites, both items of purification. As to the question at hand, you would have to looks in the god lists and see if Ezina-Kusu and Kusu both receive their own entries, this would suggest independent deites. The presence of Kusu as an epithet of the goddess Ezina does not in itself prove that Kusu was not a distinct deity, remember Mesopotamian religion was very complex and each city had its own circle of gods - some scholars will further distinguish between the pantheon of the public and offical cult, and that of the scribes (i.e. G. Rubio 2011).”

I again agree Bill; I will need to read the article in full soon so I can comment on it fully. In the ETCSL version of ‘Hymn to Kusu’ it mentions Gibil not Girra or Ĝiš-Bar (from which Girra is often referred as). Was this a later Akkadian form of the hymn or the Akkadian version on the tablet’s reverse? I need to read that article next time I get time online to do so.

“iv) “ Well, in this case, the ancient scribe had the option of spelling Erra with either ir3/er3 or ir9/er9. Of the numerous problems I felt were there in your Girra post, this was not one of them. I said "only occasionally" is it spelled ir9/er9, so you and ETCSL were not wrong about this issue, only occasionally means that yes sometimes this *is* the attested spelling. More importantly, I want to explain clearly that I am not like Ed at all: I started examining Mesopotamian stuff with him, yes, but after 1 year I split from that group and made this one because we were not alike at all. And the difference is not that I subsequently went to university for these studies and have remained there ever since - that isn't it. The difference is this: I've always been humble and apprenticed myself to the works and knowledge of the academic community and to certain scholars, trusting in their authority. Ed, on the other hand, while ostensibly academic, takes it upon himself to reinterpret ancient material and tweak things as he sees fit without any real deference to the science of the field. Our attitudes are exactly opposite. Therefore you also have a) TOD and b) enenuru and they are completely different.” (note: I deleted my comment in which you were replying to make this easier to read).

Concerning Er3 (-ra) & Ir9 (-ra) being used to used as variants by scholars, not I'm not disputing it out of hand. I'm just noting they are spelled differently. None of the signs derived from Arad could be read with a G if I'm reading them right.

ARAD= arad, er3, nitaḫ2

When combined with: RA=ra Arad & Gir3 can be read as:

Arad+Ra forms er3–ra or arad-ra or nitaḫ2-ra

where as:

Gir3+Ra forms er9-ra, gir3-ra, ĝir3-ra, ĝiri3–ra, šakkan2-ra.

Unless both sign combinations are used for Erra, they seem to be referring to different deities.

The scribes likely used Arad-ra as their way to write the Akkadian form of Erra in Sumerian cuneiform signs if the ETCSL sign list is correct as listing er3 as an Arad derived sign. If Erra is derived from: ḥarārum (as you posit & I have no reason to distrust your assertion to that this this is true) and if it is in turn derived from *ḥrr, a synonym for Burn, (Akk. Šarāpu & Semitic *ŝrp) as Char?. The ḥ element is a pharyngeal voiceless fricative. I don’t know how that would be pronounced, but you mentioned it was equated with the ĝ sound, which is ñ or ng sound. That said ḥ and ĝ are separate elements in the Sumerian word signs.

But if the scribes wrote Erra as Arad-ra/er3-ra not gir3/er9-ra in all cases, then er3-ra & er9-ra are not equitable. That is unless Erra was an epithet of Lugal-Gir3-ra/Er9-ra or Lugal-Gir3-ra/Er9-ra is an epithet Arad-ra/Er3-ra or was Er3-ra simply seen as the Akkadian form of Lugal-Gir3-ra/Lugal-Er9-ra or Gir3-ra/Er9-ra? Was on the Akkadian version of the ‘Hymn to Nergal’ is Er3.ra used separately, in the stead of Nergal ( or ) or along with Nergal?

We don’t know why both Er3-ra & Lugal-er9-ra was mentioned separately in the ‘Hymn to Nergal’ as it is highly damaged. But Er3-ra (if this is how Er3-ra was written in the original) was referenced as to addressing his King Nergal (Meslamtaea), but Lugal-er9-ra was mentioned in the second to last line, but it and previous lines are heavily damaged, and I can’t say if Lugal-er9-ra was mentioned in the Hymn to Nergal prior to this mention and what context he was. So I cannot say if by the time this hymn was written Lugal-Er9-ra was synchronized with Nergal (Meslamtaea) and used as another title or epithet for Nergal or mentioned along with Er3-ra, & Ninsuber greeting Nergal, but his lines were too damaged to translate. But in the Sumerian Er3-ra seems to be seen as a separate deity. We’ll likely never know 100%.

“v) "If it is Ku3-su3(-e) it might mean Ku3-su3 (Ezina)" <This was part of a larger query asking for insight to my over all question referring to Kusu.>

I have to say this is an example of the "Ed" way of doing things, so you have to choose which philosophy/methodology you ultimately aspire to, and dedicate yourself to that path. If it is the "Ed" way, you are probably already at your destination, but you won't find much agreement at enenuru as I am explaining. The other way is much longer and harder but I would do my best to assist. Let me explain: in "ku3-su3-e" ku3-su3 is the name, yes, and -e is a grammatical element, in this case e marks the ergative case. That the Sumerian element -e happens to be the first letter of ergative is completely coincidental, and it is also coincidental that this is the first letter or Ezina. What the ergative marker does is specify the 'doer' of the action, there think of it as Kusu+is-the-actor (Kusu-e). In this case, she is the one who purifies and cleanses hands. Should you want to go the enenuru path, as I said in my last post, you will need many philological resources and grammars in order to interpret Sumerian - all of which I can supply if you write me at:”

I covered this in part in my previous brief reply & the above. Thank you for the insight into Sumerian grammar. I’d love to have those resources on philosophy & Sumerian grammar Bill. I’ll e-mail asap. But I do want to state that I barely know Ed and I won’t presume to judge his methods or judge him as a person based upon your opinion on him (and I know that you are not asking me to). He & I share a lot in common & I like Ed. But that doesn't mean I see things the way he does on all things. As I said before I’m not here to put forth an agenda or twist myths to meet my biases. I’m here to grow my wisdom & I appreciate what you, Madness, Sheshki and other members post here.