The god Bahar-é-nun-za-ku = BÁHAR.É.NUN.ZA.TUŠ = Nun-ura

Dec 30, 2015 1:49:21 GMT -5

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Dec 30, 2015 1:49:21 GMT -5

BÁHAR.É.NUN.ZA.TUŠ

The go BÁHAR.É.NUN.ZA.TUŠ (previously read: Bahar-e-nun-za-ku) is a god who has perplexed us here at enenuru. He was first noted by us back in 2007, when his named was read in a few incantation text (see the gods to investigate thread). Recently, he puzzled us again when I posted some of that same incantation material, this time attempting to analyze the Sumerian (see the TMH 6 19 thread.

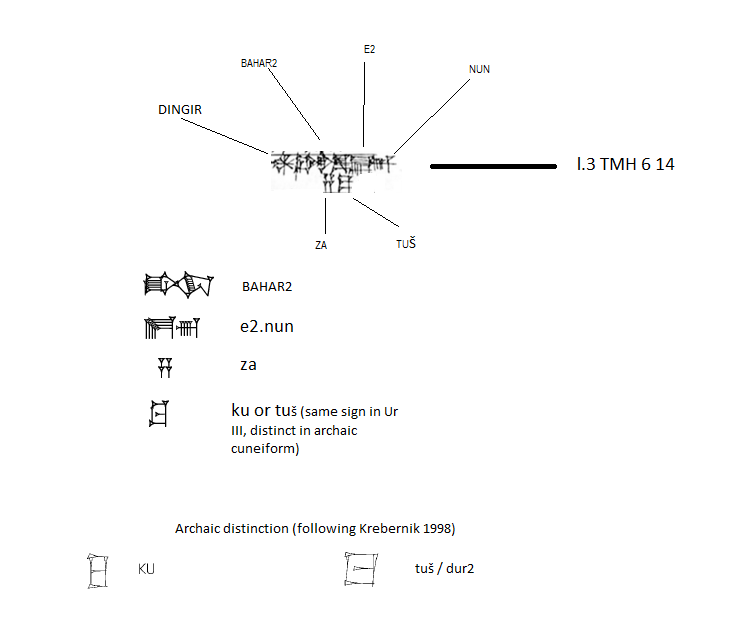

Today I have finally stumbled on a line of scholarship which furthers our understanding of this deity, if only a little. These observations were made by Marchesi and Marchetti in their 2011 work "Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia" (which Sheshki has also been utilizing lately); in their analysis of this divine name they seem to have often benefited from the philological expertise of Prof. Krebernik. Incidently, when I was in Germany I asked Krebernik about this god, on several occasions even. If I remember correctly he referred me, without too much elaboration, to these same studies of his that Marchesi and Marchetti have referenced, but until now I haven't yet followed up on this. To start with, here is Marchesi and Marchetti 2011 p. 167:

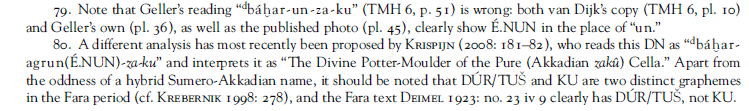

In the below illustration, let's call it fig.1, I have broken down the spelling of the god's name in one particular Ur III incantation (TMH 6 14), to be discussed further below:

fig.1

Discussion:

So what is in a name? In the case of very obscure deities like this, where we have precious little description, the interpretation of the name becomes very important and offers some of the only clues about the character of the god. Hence, Marchesi and Marchetti's careful philology is an important contribution. I will attempt to summarize their statements and break them down:

1. In Early Dynastic Royal inscriptions, the GN (Geographic Name) BÁHAR.É is known, the authors suggest that this GN is the same known from a Geographical list from the Uruk Period (aka Archaic Cities List) where it is spelled BÁHAR.É.ZA7 (See DCCLT, Archaic, Archaic Cities - although Veldhuis apparently reads this line differently). Additionally, the authors equate an entry in an ED version of the same Geographic list: BÁHAR.É.ZA7 in the Uruk version = BÁHAR.ZA7.NUN.É.TUŠ.

Why would the GN, the place, be named with the same name as the god then? As is explained above, this is a phenomenon known in Mesopotamia where the city can be indicated in the writing simply by writing the name of the god and adding the determinative ki afterwards, the example given was Nippur which can be written dEn-lil2ki.

2. Moving to the name of the deity itself, BÁHAR.É.NUN.ZA.TUŠ: First, by way of explanation, the choice to use capital letters or not in the writing of the name is somewhat arbitrary. In Sumerological convention, using capitol letters simply indicates that reading of the signs in question is uncertain or subject to change, so it is at the author's discretion. BÁHAR is simple enough and means "potter." In reading the final sign as TUŠ the authors have made an important departure I think, justified by the realization that in the earliest writings of the relevant GNs, TUŠ is a distinct sign from KU (it is wider - see fig. 1). TUŠ can represent the Sumerian verb to sit, or to dwell, hence, the god is the potter who dwells in the E2.NUN.ZA.

Now, an additional problem is: what is the E2.NUN.ZA? Well, there are various ways to take this. The authors prefer to take the NUN as a "phonetic indicator" - meaning, they believe that the ancients wrote NUN to assist in correctly reading / pronouncing the value of E2, to show this, NUN is written in superscript: E2NUN. I can't say that I fully understand this interpretation, I guess it would depend on how you believe the Sumerian word for house was supposed to have been pronounced. This argument does avoid the problem of the grammar of E2NUN.ZA , suddenely, your simply have 'house (E2NUN) - stone (ZA)' and that is simple enough.

*****Edit: After talking to our member Darkl2030 about this particular point, Marchesi and Marchetti's interpretation NUN, he explained to me that what they mean by "phonetic indicator" is that the NUN indicates an element in the gods later/actual name, nun-ur4-ra, rather than how E2 is supposed to be pronounced. The author's intent is easy to misinterpret however as this is not the standard usage of the term 'phonetic indicator' in Sumerology.

Another possibility, as Krispyn preferred, is to see E2-NUN as spelling "agrun" that is "cella". There is nothing overly controversial about this, see the ePSD entry for agrun, for example, and you will see that the signs E2 + NUN are understood to spell agrun. And phonetically, this is understandable (e approximates a and nun appproximates grun). If Marchesi and Marchetti understood house to stand in apposition to stone "house-stone" then by the same logic, an apposition "cella-stone" seems just as reasonable. Therefore we might combine different view points and interpret:

BÁHAR (Potter) É.NUN (=agrun, cella) + ZA (stone) + TUŠ (who dwells) : Divine potter who dwells in the cella.

Some follow up questions for this thread may be:

1. What is the agrun? It seems to be a word denoting cella of a divine abode, particularly that of Ningal in Ur, but it also occurs in the abzu. ePSD references [1995] P. Steinkeller, BiOr 52 706 and [1989] P. Michalowski, Lamentation over Sumer and Ur 105-106.

2. What is known about the god nun-ur4-ra who Marchetti and Marchesi have so skillfully assoicated with BÁHAR.É.NUN.ZA.TUŠ?

It's finished now.

It's finished now.