Reconstructing Mesopotamian Music

Aug 25, 2008 8:23:15 GMT -5

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Aug 25, 2008 8:23:15 GMT -5

Thread Orientation: This thread aims to consider the prospect of reconstructing Sumerian music: will the fruits of scholarship sound for us those songs from far off times? Perspective on the likelihood of restoring an authentic Sumerian sound to follow below.

As some of you may have seen, one of our new members, pizzewis, has mentioned Theo Krispijn's wonderful reconstruction of a ancient song in her intro post. We can get a small sample of this sound at the link that has been provided:

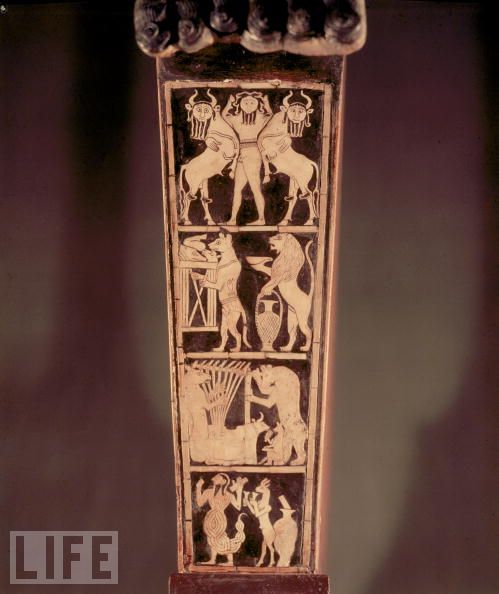

On hearing Krispijn play, I was immediately struck - it is absolutely a beautiful sound, much different then other times I have heard a reconstructed bull lyre played (in those samples, it was the a bull lyre reconstruction yes, but set to African musical themes.) The sound of Krispijn's song is mournful and pristine, and it alone gives one hope that yes Mesopotamian musical reconstructions can be approached and even achieved and performed. To imagine that the ancients themselves sounded something like this, we would know they shared something like an emotive sentiment (most at least) have these days.

Krispijn's work: prayer of an infertile woman /

However, in examining this particular reconstructed song, it must be recognized that even though it was recovered from a cuneiform tablet, and even though it was played on what (because of the fame of the archaeological find) I'll call a (reconstructed) bull lyre, the music itself is not strictly Mesopotamian. Krispijn, as our source tells us, is using music from a tablet from Ugarit, ancient Canaan, which is outside Mesopotamia proper (but which undoubtedly took heavy influence from nearby Mesopotamia.)

This article relates to a visit made by Krispijn in 2007 to the Oriental institute, where he performed this song to an enthusiastic crowd of some 30 specialists. One astute remark I'd read reflects on the notion that this is "the oldest song ever":

However it is not Krispijn who is saying this is "the oldest song ever" , that is the hype. He is in fact a scholar from Leiden with specialty in Sumerian, Akkadian and Ugartic languages and who focuses on ancient music: he would have no misconceptions about the difficulty of recreating earliest music such as from Sumer. The song Krispijn has chosen to play is from a tablet found at Ugarit from about 1200 BC, and was written in cuneiform and in the Hurrian language. His work on this tablet, which includes examination of the music and the lyrics preserved in its text, is published in the volume Studies in Music Archaeology III .. an abstract of the article reads as follows:

"Music was important in ancient Mesopotamian culture. The subject was taught in the scribal schools, for it was important for the composition of literature, and the technical construction of musical instruments was an element of instruction in mathematics. Playing musical instruments was part of the education of Mesopotamian intellectuals. Professional musicians were active in the temple and the palace. Musical theory was based on the strings of the lyre. The names of the strings and the string combinations are known, and their etymologies are clues to the original stringing of the lyre, the tuning procedures and connections with other musical instruments. The names of the string combinations are also apparently the terms for tuning scales. Mesopotamian musical terminology was taken over into Hurrian. This now makes it possible to reconstruct the accompaniment for the partly understandable Hurrian ‘prayer of an infertile woman’ [12th century B.C., from Ugarit]."

Indeed, that that music had a special place in the enthusiasms of Mesopotamian intellectuals, and that the art of music can be thought of as a gift from Mesopotamian to younger cultures like the Ugarities, is made apparent or suggestible by evidence from the Sumerian literature itself. An example of the Sumerian zeal for music and its technical aspects is a boast of the Ur III king Shulgi, who says:

(A praise poem of Šulgi (Šulgi B): t.2.4.2.02)

Cuneiform sources/

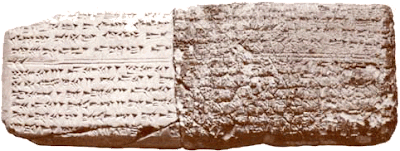

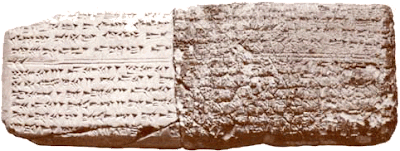

Although there have been attempts to examine and to make sense of those earliest attestations of music, those from the Sumerian context, there are apparently textual limitations and difficulties of interpretation which prevent the successful playing of a Sumerian song - We should in more detail examine those problem on this thread in weeks to come... But for now I have found a nice article reflecting on the Krispijn's work at the following blog by Mark Alburger. Alburger's blog makes some photos of the tablet Krispijns uses available:

Krispijn had said, as is quoted in the Chicago tribune: ""Fragments have been found of other songs..but not enough was left to be able to reconstruct. Other scholars began the work, and, about 15 years ago, I started to figure it out." In this blog article we get a little more information about those who efforts must have helped Krispijn:

"In 1972, after 15 years of research Anne Draffkorn Kilmer (Professor of Assyriology at the University of California, and a curator at the Lowie Museum of Anthropology at Berkeley) transcribed the music [from this above pictured tablet] as a form of harmony, two or more notes played at the same time, which was previously thought to be non-existent altogether in ancient music.

The top parts were the words and the bottom half instructions for playing the music. The song, it turns out, is in the equivalent of the diatonic "major" ("do, re, mi") scale. In addition, as Kilmer points out: "We are able to match the number of syllables in the text of the song with the number of notes indicated by the musical notations." This approach produces harmonies rather than a melody of single notes. The chances the number of syllables would match the notation numbers without intention are astronomical."

(picture of Kilmer's notation from the same tablet used by Krispijn)

Alburger than continues: "In March of 2007 the North American premiere of a vocal rendition of the piece was given at the Oriental Institute on the University of Chicago campus. Dr Theo J. H. Krispijn, a professor in Assyriology at Leiden University in the Netherlands and an accomplished vocalist, performed the song, complete with lyrics, and accompanying himself on a reproduction of an ancient stringed instrument, the lyre."

Thanks to some luck with google today, I also have found an interesting comment that was made on the Chicago based ANE yahoo discussion group, just after Krispijn's visit to Chicago. Someone wondered: "What is the relation between Krispijn's performance and a reconstruction done by Kilmer and her team almost 30 years ago? " Kevin Edgecomb replies here, and says:

I was wondering that, too. It was Anne Kilmer, Richard Crocker, and Robert

Brown. The latter built the large Sumerian harp replica (Crocker sings the

Hurrian hymn to its accompaniment) and the smaller Canaanite harp replica (with

which Kilmer sings). The album (vinyl!) with accompanying explanatory booklet

is called "Sounds From Silence." I've got a copy. It's quite eerie,

reminiscent of old Roman chant, the pre-Gregorian stuff.

It looks like it's still available from this online store, along with some other

interesting ancient musicy stuff:

www.bellaromamusic.com/store.html

So we have more to consider about ancient music, and about the scholarly offerings that exist and may overlap each other, but seem to be moving forward. Still to come - Reading and efforts to explore the technical side of cuneiform music "notation" ; Michalowski's perspective on Sumerian music ; and just what is the problem with reconstructing Sumerian music??

Considering Theo Krispijns "Oldest Song"

As some of you may have seen, one of our new members, pizzewis, has mentioned Theo Krispijn's wonderful reconstruction of a ancient song in her intro post. We can get a small sample of this sound at the link that has been provided:

On hearing Krispijn play, I was immediately struck - it is absolutely a beautiful sound, much different then other times I have heard a reconstructed bull lyre played (in those samples, it was the a bull lyre reconstruction yes, but set to African musical themes.) The sound of Krispijn's song is mournful and pristine, and it alone gives one hope that yes Mesopotamian musical reconstructions can be approached and even achieved and performed. To imagine that the ancients themselves sounded something like this, we would know they shared something like an emotive sentiment (most at least) have these days.

Krispijn's work: prayer of an infertile woman /

However, in examining this particular reconstructed song, it must be recognized that even though it was recovered from a cuneiform tablet, and even though it was played on what (because of the fame of the archaeological find) I'll call a (reconstructed) bull lyre, the music itself is not strictly Mesopotamian. Krispijn, as our source tells us, is using music from a tablet from Ugarit, ancient Canaan, which is outside Mesopotamia proper (but which undoubtedly took heavy influence from nearby Mesopotamia.)

This article relates to a visit made by Krispijn in 2007 to the Oriental institute, where he performed this song to an enthusiastic crowd of some 30 specialists. One astute remark I'd read reflects on the notion that this is "the oldest song ever":

"That’s probably a bit of hyperbole; it would be more accurate to say it is the oldest extant song we can reasonably recreate."

However it is not Krispijn who is saying this is "the oldest song ever" , that is the hype. He is in fact a scholar from Leiden with specialty in Sumerian, Akkadian and Ugartic languages and who focuses on ancient music: he would have no misconceptions about the difficulty of recreating earliest music such as from Sumer. The song Krispijn has chosen to play is from a tablet found at Ugarit from about 1200 BC, and was written in cuneiform and in the Hurrian language. His work on this tablet, which includes examination of the music and the lyrics preserved in its text, is published in the volume Studies in Music Archaeology III .. an abstract of the article reads as follows:

"Music was important in ancient Mesopotamian culture. The subject was taught in the scribal schools, for it was important for the composition of literature, and the technical construction of musical instruments was an element of instruction in mathematics. Playing musical instruments was part of the education of Mesopotamian intellectuals. Professional musicians were active in the temple and the palace. Musical theory was based on the strings of the lyre. The names of the strings and the string combinations are known, and their etymologies are clues to the original stringing of the lyre, the tuning procedures and connections with other musical instruments. The names of the string combinations are also apparently the terms for tuning scales. Mesopotamian musical terminology was taken over into Hurrian. This now makes it possible to reconstruct the accompaniment for the partly understandable Hurrian ‘prayer of an infertile woman’ [12th century B.C., from Ugarit]."

Indeed, that that music had a special place in the enthusiasms of Mesopotamian intellectuals, and that the art of music can be thought of as a gift from Mesopotamian to younger cultures like the Ugarities, is made apparent or suggestible by evidence from the Sumerian literature itself. An example of the Sumerian zeal for music and its technical aspects is a boast of the Ur III king Shulgi, who says:

(A praise poem of Šulgi (Šulgi B): t.2.4.2.02)

I, Šulgi, king of Urim, have also devoted myself to the art of music. Nothing is too complicated for me; I know the full extent of the tigi and the adab, the perfection of the art of music. When I fix the frets on the lute, which enraptures my heart, I never damage its neck; I have devised rules for raising and lowering its intervals. On the gu-uš lyre I know the melodious tuning. Tuning, string, I am familiar with the sa-eš and with drumming on its musical soundbox. I can take in my hands the miritum, which ……. I know the finger technique of the alĝar and sabitum, royal creations. In the same way I can produce sounds from the urzababitum, the ḫarḫar, the zanaru, the ur-gula and the dim-lu-magura. Even if they bring to me, as one might to a skilled musician, a musical instrument that I have not heard before, when I strike it up I make its true sound known; I am able to handle it just like something that has been in my hands before.ng, unstringing and fastening are not beyond my skills. I do not make the reed pipe sound like a rustic pipe, and on my own initiative I can wail a šumunša or make a lament as well as anyone who does it regularly.

Cuneiform sources/

She [the goddess] let the married couples have children,

She let them be born to the fathers

But the begotten will cry out, 'She has not borne any child'

Why have not I as a true wife borne children for you?

She let them be born to the fathers

But the begotten will cry out, 'She has not borne any child'

Why have not I as a true wife borne children for you?

(Translated Lyrics from 'prayer of an infertile woman')

Although there have been attempts to examine and to make sense of those earliest attestations of music, those from the Sumerian context, there are apparently textual limitations and difficulties of interpretation which prevent the successful playing of a Sumerian song - We should in more detail examine those problem on this thread in weeks to come... But for now I have found a nice article reflecting on the Krispijn's work at the following blog by Mark Alburger. Alburger's blog makes some photos of the tablet Krispijns uses available:

Krispijn had said, as is quoted in the Chicago tribune: ""Fragments have been found of other songs..but not enough was left to be able to reconstruct. Other scholars began the work, and, about 15 years ago, I started to figure it out." In this blog article we get a little more information about those who efforts must have helped Krispijn:

"In 1972, after 15 years of research Anne Draffkorn Kilmer (Professor of Assyriology at the University of California, and a curator at the Lowie Museum of Anthropology at Berkeley) transcribed the music [from this above pictured tablet] as a form of harmony, two or more notes played at the same time, which was previously thought to be non-existent altogether in ancient music.

The top parts were the words and the bottom half instructions for playing the music. The song, it turns out, is in the equivalent of the diatonic "major" ("do, re, mi") scale. In addition, as Kilmer points out: "We are able to match the number of syllables in the text of the song with the number of notes indicated by the musical notations." This approach produces harmonies rather than a melody of single notes. The chances the number of syllables would match the notation numbers without intention are astronomical."

(picture of Kilmer's notation from the same tablet used by Krispijn)

Alburger than continues: "In March of 2007 the North American premiere of a vocal rendition of the piece was given at the Oriental Institute on the University of Chicago campus. Dr Theo J. H. Krispijn, a professor in Assyriology at Leiden University in the Netherlands and an accomplished vocalist, performed the song, complete with lyrics, and accompanying himself on a reproduction of an ancient stringed instrument, the lyre."

Thanks to some luck with google today, I also have found an interesting comment that was made on the Chicago based ANE yahoo discussion group, just after Krispijn's visit to Chicago. Someone wondered: "What is the relation between Krispijn's performance and a reconstruction done by Kilmer and her team almost 30 years ago? " Kevin Edgecomb replies here, and says:

I was wondering that, too. It was Anne Kilmer, Richard Crocker, and Robert

Brown. The latter built the large Sumerian harp replica (Crocker sings the

Hurrian hymn to its accompaniment) and the smaller Canaanite harp replica (with

which Kilmer sings). The album (vinyl!) with accompanying explanatory booklet

is called "Sounds From Silence." I've got a copy. It's quite eerie,

reminiscent of old Roman chant, the pre-Gregorian stuff.

It looks like it's still available from this online store, along with some other

interesting ancient musicy stuff:

www.bellaromamusic.com/store.html

So we have more to consider about ancient music, and about the scholarly offerings that exist and may overlap each other, but seem to be moving forward. Still to come - Reading and efforts to explore the technical side of cuneiform music "notation" ; Michalowski's perspective on Sumerian music ; and just what is the problem with reconstructing Sumerian music??

Well that lyre of Ur project is interesting because of the impressive effort these people made at authentically reconstructing the instruments themselves - including alot of real gold for the lyre. I had previously mistaken the pipes in that video as non-Sumerian. For this effort alone the project is impressive.

Well that lyre of Ur project is interesting because of the impressive effort these people made at authentically reconstructing the instruments themselves - including alot of real gold for the lyre. I had previously mistaken the pipes in that video as non-Sumerian. For this effort alone the project is impressive.