|

|

Post by sheshki on Apr 6, 2015 14:55:15 GMT -5

here is what Black and Green, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia has: rhomb The `rhomb' or 'lozenge' is a pointed oval within four enclosing perimeter lines. It is a very common motif in Mesopotamian art from early historic times until the Neo-Assyrian Period. Its significance is uncertain. The symbol has been variously explained as a grain of corn, a date-stone, a symbol of earth, an eye, or a woman's vulva. That it is closely associated in art with the goddess Ištar (Inana) and is similar to the clay models of vulvae found in her temple at Asšur supports the last suggestion. The rhomb seems to have had a magically protective function. concerning the Kassite cross go >>>here |

|

|

|

Post by symbolic on Apr 7, 2015 4:14:11 GMT -5

!! That is very good of you, thanks for that, very informative. It's interesting that symbols with such frequency are still in a grey area as far as identification is concerned.

(edited: I should read and respond in less haste:)

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Apr 9, 2015 20:34:36 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Apr 9, 2015 20:39:22 GMT -5

and a nice example of the cross  |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Apr 11, 2015 0:30:58 GMT -5

Symbolic: In addition to the insights Sheshki provides above, I suggest the following article for the rhomb / lozenge symbolism: www.matrifocus.com/LAM06/spotlight.htm The author does have a feminist bent, which I suggest should be borne in mind. Not to imply that the information is inherently incorrect therefore, but we all have our biases. In particular, I believe Stuckey has reduced the laborious task of finding other scholars who say anything substantial about this symbol which after all is just a shape, one that occurs frequently in Mesopotamian art, but the ancients never left us a note to explain 'we like this shape because it makes us think of X.' You may want to follow up by referencing the Goff and the Göhde, both of these works are given in Stuckey's bibliography. I have given Goff at the below link, please contact me by mail (bill.mcgrath@utoronto.ca) if you need the Göhde as well. Goff here |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Apr 14, 2015 13:16:09 GMT -5

Very nice example of a standard  , unfortunatly i do not have many details about it. Found it via facebook. Thanks to Adam for the information. Here<<<< is the link to the page where he found it.  edit: with darkl´s help (he deciphered a year name on the tablet) i was able to locate the tablet, after scrolling through hundreds and hundreds of tablets...oh boy  So it is >>>this (P235442)<<< one. Here is a collection of the four imprints of the standard.  During my search-a-ton i found two more standards. P100578  P106618  |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Apr 19, 2015 16:59:46 GMT -5

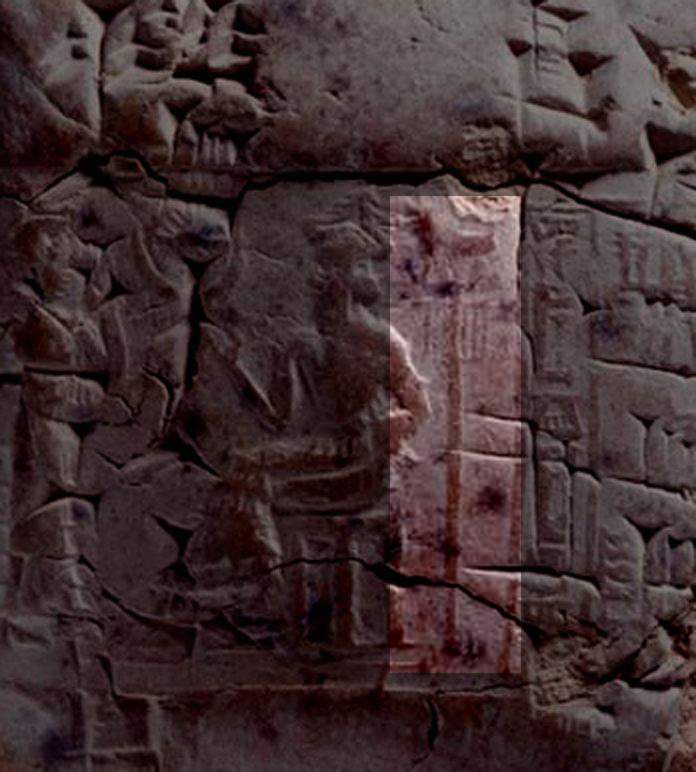

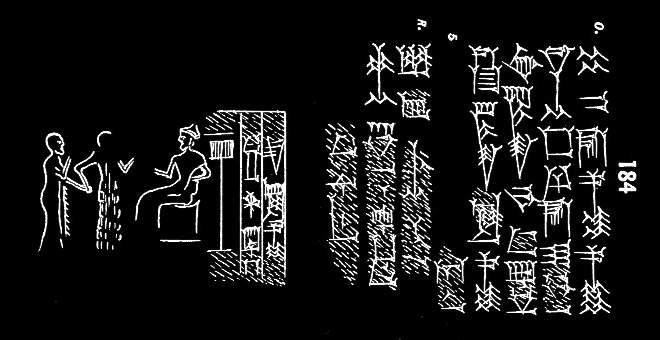

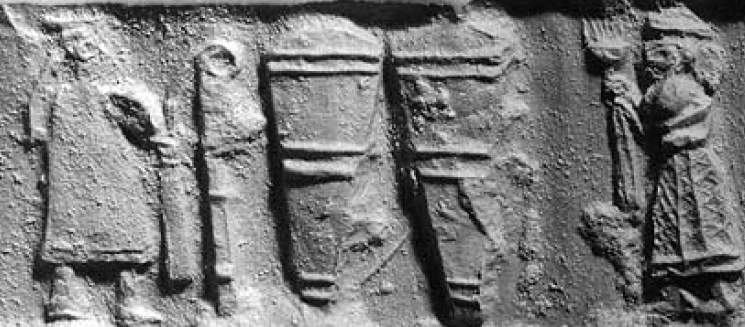

Some nice investigating Sheshki, thanks to you and Adam and Darkl. Well, about the original seal that caught your eye (P235442) looks like a presentation scene, which were frequent in Ur III iconography: a mortal (usually the king) is presented by his personal god to a seated god, probably the city god. As for the standard in question, it seems to have the 'fringed tassle' (see the summaries of Szarzynska at the top of this page); as for the 'divine emblem' that is mounted on top of the standard, it looks like a 4 legged animal to me. Perhaps a lion. It has been demonstrated by C. Suter (Gudea's Temple Building) that the heraldic animal of Ningirsu was the lion and so that is my guess at the moment. On the other hand, since the item comes from Umma and Inanna would be more central there I believe, I could change my mind.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Apr 19, 2015 18:58:05 GMT -5

The picture is not very clear, unfortunately. To me it kinda looks like a bull... Uruk maybe  This is post 1000. Invisible drinks to everyone  |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jun 8, 2015 11:27:39 GMT -5

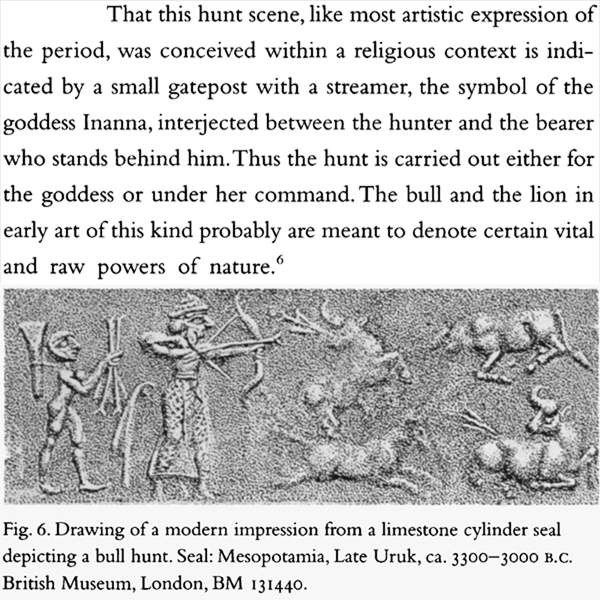

From: Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus >>>link<<< |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 8, 2015 18:39:19 GMT -5

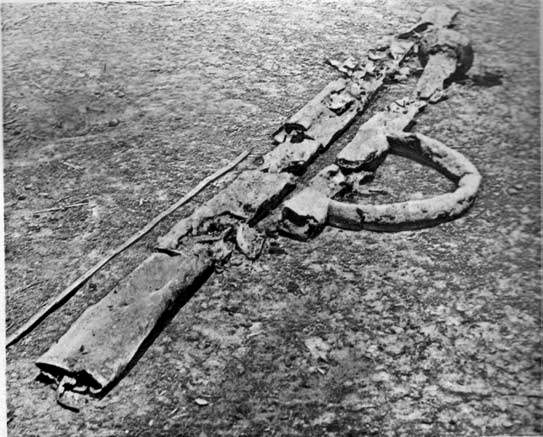

From: Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia by Gianni Marchesi and Nicolò Marchetti Copper standard found in the temple of Ningirsu in Girsu  "It may be interesting to note that both the plaque and the “Standard” were found in the northwest wing, i.e., in the vicinities of the newly-found Red Temple (below Middle Bronze Age Temple D) and may thus have been dedicated in a temple rather than in a palace con- text (a situation similar to the “Enceinte Sacrée” of the Pre-Sargonic Palace in Mari)." |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Nov 15, 2015 16:57:17 GMT -5

From: Non-Textuality in the Ancient Near East Klaus Wagensonner, 2009 § 6 Divine symbols We already met symbols referring to or representing divinities in the discussion of Old Babylonian cylinder seal impressions. Such symbols are roughly attested from the middle of the 3rd millennium onwards. Recently Michael Herles dealt with the archaeological and textual evidence concerning the anthropomorphic representation of deities and their connection to the symbols (2006). Since identifying a symbol with a specific deity is still in many cases problematic, the best identification can only be provided by accompanying inscriptions. “Legends” are unfortunately, apart from the glyptic art, only attested in rare cases. For the second half of the 2nd millennium the best evidence is provided by monuments which, generally spoken, commemorate royal grants of land. These objects are called Kudurrus or Narûs. The most recent study of those artefacts was conducted by Kathryn Slanski (2003). Although her work was critically reviewed by John Brinkman (2004) and Dominique Charpin (2002), it offers a valuable insight into the corpus of approximately 150 monuments. It is not the place here to go into detail, but the legal transactions attested in the inscriptions are often followed by extensive curse formulae containing references to deities. In addition to the inscription the grant of land is often supported by divine symbols carved onto the monument’s surface. Only in extremely rare cases the symbols are accompanied by legends. An often cited example of a possible correlation between text and image is the Kudurru published in Scheil (1900: 86ff.), which should be quoted here shortly. In ll.iv:30f. the content of the preceding lines is declared: “17 emblems of the great gods”. The eye-catching fact is that we find on two sides of the artefact an array of 17 divine symbols, which led to many interpretations. The passage reads as follows: iv:šubtu u šukusu ša Anim šar šamê the socle and the headdress of Anu, king of the sky;

iv:girgilu allaku ša Ellil bel šadê the gull, courier of Enlil, lord of the mountains;

iv:mum u suhurmašu aširtu rabitu ša Ea emblem and goat-fish, the great socle of Ea;iv:Šulpa’e Šulpa’e,

iv:Išhara Išhara,

iv:u Aruru and Aruru;

iv:usqaru buginna magurru ša Sîn crescent, trough, (and) magurru-ship of Sîn;

iv:niphu namrirru ša dayyani rabî Šamaš the radiant sun disk of the great judge Šamaš;

iv:isqarrurtu purrurtu ša Ištar belet šadî/matati the jagged-edged emblem of Ištar, lady of the mountains/lands;

iv:buru ekdu ša Adad mar Anim the fierce calf of Adad, son of Anu;

iv:Girru ezzu šipru ša Nuska raging Girru, envoy of Nuska;

iv:Šuqamuna Šuqamuna

iv:u Šumaliya and Šumalia,

iv:ilanu murtamu the gods who love each other;

iv:Nirah šipru ša Ištaran Nirah, the envoy of Ištaran;

iv:Šar’ur(ur) Šargaz Šar’ur, Šargaz,

iv:u Meslamta’e(a) and Meslamta’e(a);

iv:masab šubbati a reed basket,

iv:markasu rabû ša Esikilla the great rope of the (temple) Esikila.”

Although the majority of those described “emblems” allow – due to our modern point of view – only a few comparisons to the image, we are dealing here with an interesting source considering divine symbols. Zainab Bahrani states, that “reading the text on royal images as a serious mode of writing rather than a repetitive apparatus allows for a rethinking of the perception of statuary in antiquity and a far more complex understanding of the power of such images than has been allowed them by traditional scholarship” (2003: 191f.). And indeed, there is a remarkable object dating to the Middle Assyrian period, which was found in a secondary deposit in a sealed room of the Ištar-temple in the city of Assur (modern Qal’at Šerqat) (fig. 18a). By virtue of the depictions on this cult pedestal we may make a good link to the “socles” dealt with on the afore-mentioned Kudurrus. That cult pedestal, labelled “Symbolsockel” by the excavator Walter Andrae, was endowed by the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I (1243- 1207 BC), who dedicated the object to the god Nuska, the god of light. The much discussed relief carved on the front depicts the king represented in a rare kind of narrative, standing and kneeling in front of a pedestal whose shape is exactly the same as the round-shaped object. But on the image we find the depiction of a tablet and a stylus, which normally refer to the scribe god Nabû. The cult pedestal was recently interpreted by Zainab Bahrani who views “the inscription on the altar of Tukulti- Ninurta not as a separate source of information for the visual image but as part of the signifying logic of the monument as a whole, a monument which (she takes) to be comprised of both text and image” (2003: 192). The text carved at the bottom of the pedestal reads as follows: nemed Nuska sukkalli siri ša Ekur “Cult platform of Nuska, chief vizier of the Ekur,

naši hatti / ešreti bearer of the just sceptre,

muzziz pan Aššur u Ellil ša servant of (the gods) Aššur and Enlil, who

umišam-ma / teslet daily

Tukulti-Ninurta šar naramišu / repeats the petition of Tukulti-Ninurta, his beloved

ina pan Aššur u Ellil ušannû-ma king, before Aššur and Enlil. (...)”

Zainab Bahrani – in view of the afore-mentioned statements made by her – tried to compare image and text without tearing them apart and looking on them separately (2003: 192ff.). Her methodology is definitely striking by looking on the orthography of the god Nuska who is written with the sign-sequence PA.TUG 2. In the text the god is called the “bearer of the just sceptre”. The sceptre, written gišGIDRI/PA is part of the divine name. Secondly the verb šanû, “to repeat”, literally refers to the repetition of the royal representation on the pedestal. Therefore, Bahrani’s interpretation of this object as an “integral visual-verbal monument” (2003: 199) is rather appropriate. ... Finally I want to rivet attention to a very interesting passage in a Sumerian-Akkadian account of a divine journey dealing with the goddess Nin-Isina(k) who travels with her entourage from her hometown Isin to Nippur, where Enlil, the supreme god of the Sumerian pantheon, resides. This composition particularises the position of each divinity in the procession in ll.6-12.72 In l.11, anyway, the deified emblem ( dšu-nir) is “placed” in front of the procession and therefore objectified: gidlam-a-ni ur-sag dpa-bil 2-sag hi-li-a mu-un-DU dumu-ki-ag 2-ga 2-ni dda-mu-ša 6-ga nu-nus-zi dgu-nu-ra dalad-ša 6-ga e 2-gal-mah-a-ne 2 egir-ra-na mu-un-su 8-ge-eš dudug-ša 6-ga a-a- d+en-lil 2-la 2 zi-da-na mu-un-DU dlama 2-ša 6-ga en dnun-nam-nir-ra gub 3-bu-na mu-un-DU dšu-nir-ra-a-ne 2 zalag 2-dutu-gin 7 igi-a-ni-še 3 si mi-ni-ib 2-se dšu-mah sukkal-zi-e 2-gal-mah-a igi-še 3 mu-un-DU “Her spouse the hero Pabilsag walks in joy,

(her) beloved child Damušaga, the righteous woman Gunura,

[and] Aladšaga walk behind her to the (temple) Egalmah.

Udugšaga, the ‘father of Enlil’ walks at her right side.

Lamašaga, the ‘lord Nunamnir’ walks at her left side.

(Her) (deified) emblem, which is like the splendour of the sun, is set before her.

Šumah the righteous messenger of the Egalmah walks at front.” |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Nov 18, 2015 18:46:26 GMT -5

From: Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia, by Gianni Marchesi and Nicolò Marchetti (2011) In addition to the famous alabaster vase (the so-called Warka vase), this deposit contained seven cylin- der seals, four of which show the “priest-king” with a net skirt, a trait that appears to be characteristic of the Jemdet Nasr period (cf. n. 14 above), which is also the date of the deposit. On a seal in elaborate style, he is shown holding an ear of barley and grazing two sheep, behind and in front of which are, respectively, an ear of barley and a bundle of reeds with a volute at the top (“Schilfringbundel”), unanimously interpreted as the symbol of In`anak on the basis of its use as a pictogram to indicate this deity (Pl. 47:2). The same two symbols—the constant association of which indicates that the ear of barley is not merely an offering but instead some kind of emblem—recur on four schematic seals carrying the meeting scene, where, between the “priestking” and the female figure with the two-pointed tiara (the “goddess”), also attested on the Warka vase , there are always two baskets of offerings (Pl. 47:3–5). The constant duplication not only of the symbol of In`anak but also of all of the offerings, notably the baskets, vases, and rhyta, is undoubtedly peculiar and may indicate that these are intended for two individuals, namely, the “goddess” and the “priest-king.” On another seal in the elaborate style, the “priest-king” is shown on a boat in front of a bull-shaped altar, above which are two “Schilfring- bundeln” (Pl. 47:6). Given the close association between the “priest-king” and the bull suggested by the seal impression from Choga Mish , one could assume that the bullshaped altar possibly refers to the “priest-king.” We cannot, however, rule out that the altar with the “Schilfringbundeln” hints at the “goddess” instead, as could be deduced from the fact that, on another seal from Uruk, the “priest-king” (holding an ear of barley between his hands) stands in front of the usual two baskets and a bull-shaped altar, which replaces in this case the “goddess” in the meeting scene; a third possibility, that the altar supports a semi-pictographic writing of a toponym, ... ... 27Hockmann (2008) has recognized in the upper frieze of the Warka vase and in three other seals (Pl. 48:6, 9, and Amiet 1980: no. 643) the writings for Nippur, Kutha, Zabalam, and Urum. In one of these seals, which is fragmentary (Pl. 48:9; Amiet 1980: no. 654; Basmachi 1994: 9, no. 2), the altar/pictogram rests on a feline. ... Although it is possible that the “priest-king” is in fact the EN, the nature of Inªanak is of such complexity that one may wonder whether the “Schilfringbundel” was associated with the “priest-king” as well as the “goddess.” Examples of ringposts from Early Dynastic seal impressions. Interesting here is picture 5, where there is a lion-like figure instead of a bull.         |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Nov 25, 2015 11:20:42 GMT -5

From: Mesopotamische Standarten in literarischen Zeugnissen by Beate Pongratz-Leisten

Here is a rough translation of the part i found interesting since the text is in german.

In the Šulgi hymn (Šulgi B) there is a building or room mentioned where standards are kept, the e2 šu-nir. Standards (šu-nir) also received offerings according to sumerian administrative texts.

The archaeological material suggests an inclusion of standards in the daily cult (Tukulti-Ninurta), were they brought to a battle, as a representative of the god, the cultic rituals including offerings and sacrifices, took place in a tent (examples from Aššurnasirpal and Senacherib).

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 4, 2015 13:19:17 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 4, 2015 15:48:10 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by hukkana on Dec 5, 2015 4:20:46 GMT -5

I'm really interested if anyone has a picture of that Ur Cemetery seal (footnote # 142) showing "combat among the gods".

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 5, 2015 10:39:11 GMT -5

The books in question are "Böhmer, Rainer Michael, Die Entwicklung der Glyptik während der Akkad-Zeit"

and "Ur excavations X" by L.Legrain. Wasn´t able to access them so far.

|

|

|

|

Post by hukkana on Dec 5, 2015 11:10:24 GMT -5

Thanks for trying either way.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Dec 8, 2015 15:25:16 GMT -5

Irritatingly, I don't seem to have access to the Böhmer either. Have you tried the Archive of Mesopotamian Archaeological Reports (AMAR) website yet? I've lost the URL to the site.

|

|

|

|

Post by hukkana on Dec 9, 2015 3:00:36 GMT -5

Irritatingly, I don't seem to have access to the Böhmer either. Have you tried the Archive of Mesopotamian Archaeological Reports (AMAR) website yet? I've lost the URL to the site. I don't think I've ever heard of that site before. And the problem is I don't know what the note on it says. As far as I've gone over the text, three times or so, the part posted here only seems to contain note 143, not 142 or any of the others. |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Dec 9, 2015 4:06:25 GMT -5

Okay, I'll talk to Sheshki and maybe we can dig up some resource on this, if I have to, may even cart my lazy rear to an actual physical library, which has always been an option. By the way Hukanna, I love your contributions here, even so, would you be able to refrain from using the 'quote post' feature ? I know it is your habit, but it increases clutter.

|

|

|

|

Post by hukkana on Dec 9, 2015 4:27:10 GMT -5

Sorry. The reason I use it is so that the person who I'm responding to gets notified of the response. I assume that's how the notifications on here work anyway, if I didn't miss anything.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 9, 2015 20:20:47 GMT -5

Here is footnote 142, it´s basically what i posted earlier.  |

|

|

|

Post by hukkana on Dec 10, 2015 7:24:21 GMT -5

Thanks, I just needed to see the note in question. Granted I'll have to do some digging to find out what the titles of those individual works are but I needed somewhere to start from.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 12, 2015 14:14:30 GMT -5

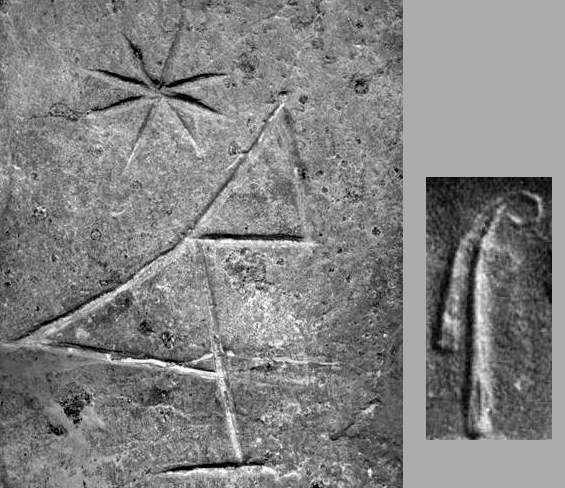

A nice example of the developement of the MUŠ 3 (Inanna) sign from the symbol of the ringpost. From: P222772 90° turned  |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Dec 22, 2015 20:34:03 GMT -5

Sheshki: This is in response to your post made above, Dec. 4 2015, concerning the animal footed "standard." I occurs to me that we have seen animal footed object before at enenuru, 7 years ago or so. These were somewhat obscure objects from Kish and Eshnunna, but reading of the posts on the relevant thread, one gets the sense that they were for ritual purposes, specifically, offerings may have been placed on them. Perhaps this "standard" is not a standard but something to place objects to be offered on? enenuru.proboards.com/thread/138/misc-observations-on-art But more interesting than our original thread dealing with animal legged objects, is perhaps the thread I will link below dealing with wall plaques from Nippur. enenuru.proboards.com/thread/494/early-image-divine First, it is art from the same city (Nippur). Secondly, if you scroll to the image labelled "Cult Stand A" , you see a bull legged cult stand, as it was called by one scholar, with apparently 2 ropes dangling from it. I guessed, and still do guess, that such a stand may have been used to tie a sacrificial animal that was to be slaughted for the god, i.e. a goat. It is possible that the object in the seal is the same (perhaps the "sandal" is not a sandal but a rope device for binding). |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Sept 28, 2016 0:51:02 GMT -5

www.academia.edu/27976894/The_Standards_on_the_Victory_Stele_of_Naram-Sin The above link is to a paper written by an academia.edu contact of mine, Renate van-Dijk-Coombes, a student from the U. of Stellenbosch. Her article explores the standards of the Victory stele Naram-sin; importantely, her article relates that scholars have divided Standards into 6 categories: 1) divine standards, 2) royal standards, 3) standards in a ritual context, 4) standards in judicial procedures, 5) standards on military campaigns, and 6) standards in an architectural context. She finds that the standards present on Naram=sin's victory stele represent the first visually attested military standards in Mesopotamian record.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 13, 2017 17:23:49 GMT -5

Terracotta fragment from Ishchali from OIP 98 |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 3, 2022 14:21:42 GMT -5

(for the complete article including all the citations and footnotes see-->Reallexikon der Assyriologie Vol. 14, p.414

dUrigallu. The word urigallu (uringallu/uriggallu,

from Sum. uri3/urin and uri3gal)

refers to standards which

symbolized the divine presence (usually spelled as logogram

URI3.GAL and GI.URI3.GAL, also syll. u2-ri-gal-

lu, u2-ri-gal-li, u2-rin-gal-li).

Standards accompanied the army and

played a role in various rituals. Deified

standards, prefixed with the divine determinative

(dURI3.GAL, dUri3-gal-lum, dU2 -ri-gal-la),

are also attested in the later periods.

Šamši-Adad V claims to have captured the

Bab. king Baba-aḫa-iddina with the deified

standard (dURI3.GAL) that preceded him;

Ass. inscriptions refer several times to these deified standards

preceding the king in battle. The most detailed evidence on deified

standards stems from the NB archive of

the Eanna (Ayakku) temple in Uruk, where two

such objects are known: the Divine U. of

Ištar (dUri3-gal-lum ša2 dINNIN UNUGki), and the Divine U. of

Usur-amassu (dUri3-gal-lum ša2 dURI3-INIM-su).

They received offerings of meat on specific ritual occasions

and a few texts record disbursements

of red-colored wool for their “turbans”

(paršigu), which probably refers to the

tassels attached to the top of the shaft holding

the standard. One NB text from Sippar

mentions “the processional way of the

Deified Standard of the goddess Šarrat-

Sippar". Texts from Uruk, Sippar and

other sites also mention deified standards

not specifically attached to a deity. They

continue to be attested at Uruk until the

Seleucid period. The logogram dURI3.GAL can also denote

the god Nergal.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 10, 2023 12:45:57 GMT -5

|

|