asakku

dubĝal (scribes assistent)

Posts: 51

|

Elam

May 5, 2013 7:29:50 GMT -5

Post by asakku on May 5, 2013 7:29:50 GMT -5

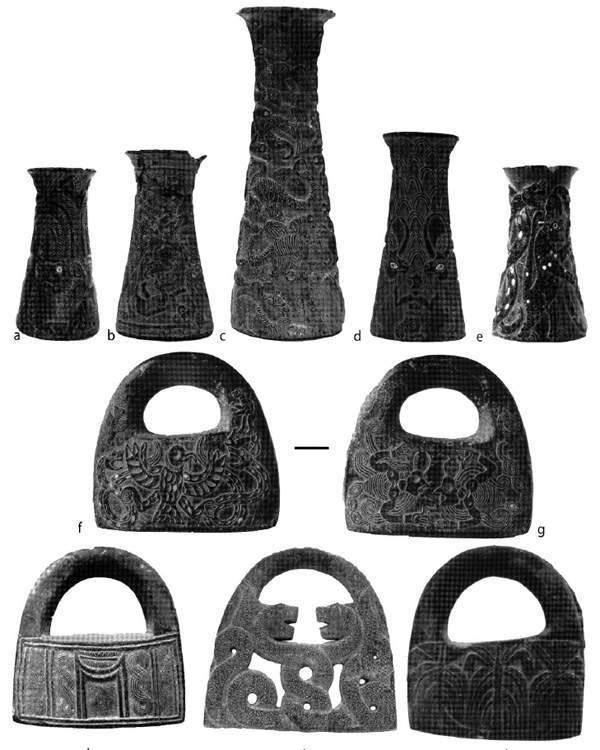

Elam is a topic, that is not very popular of what i have seen among Assyriologists. Mostly because of how little we know about this Empire. A shot cut about the history of all who don't know about Elam:The Iranian Plateau did not experience the rise of urban, literate civilization in the late 4th and early 3rd millennia on the Mesopotamian pattern but the lowland Khuzestan did. It was the Elamite Civilization. Geographically, Elam included more than Khuzestan; it was a combination of the lowlands and the immediate highland areas to the north and east. Elamite strength was based on an ability to hold these various areas together under a coordinated government that permitted the maximum interchange of the natural resources unique to each region. Traditionally this was done through a federated governmental structure. Closely related to that form of government was the Elamite system of inheritance and power distribution. The normal pattern of government was that of an overlord ruling over vassal princes. In earliest times the overlord lived in Susa, which functioned as a federal capital. With him ruled his brother closest in age, the viceroy, who usually had his seat of government in the native city of the currently ruling dynasty. This viceroy was heir presumptive to the overlord. Yet a third official, the regent or prince of Susa (the district), shared power with the overlord and the viceroy. He was usually the overlord's son or, if no son was available, his nephew. On the death of the overlord, the viceroy became overlord. The prince of Susa remained in office, and the brother of the old viceroy nearest to him in age became the new viceroy. Only if all brothers were dead was the prince of Susa promoted to viceroy, thus enabling the overlord to name his own son (or nephew) as the new prince of Susa. Such a complicated system of governmental checks, balances, and power inheritance often broke down despite bilateral descent and levirate marriage (i.e., the compulsory marriage of a widow to her deceased husband's brother). What is remarkable is how often the system did work; it was only in the Middle and Neo-Elamite periods that sons more often succeeded fathers to power. Elamite history can be divided into three main phases: the Old, Middle, and Late, or Neo-Elamite, periods. In all periods Elam was closely involved with Sumer, Babylonia, and Assyria, sometimes through peaceful trade, more often through war. In like manner, Elam was often a participant in events on the Iranian Plateau. Both involvements were related to the combined need of all the lowland civilizations to control the warlike peoples to the east and to exploit the economic resources of the plateau. Old Elamite Period The earliest kings in the Old Elamite period may date to approximately 2700 BCE. Already conflict with Mesopotamia, in this case apparently with the city of Ur, was characteristic of Elamite history. These early rulers were succeeded by the Awan (Shustar) dynasty. The 11th king of this line entered into treaty relations with the great Naram-Sin of Akkad (c. 2254 - c. 2218 BCE). Yet there soon appeared a new ruling house, the Simash dynasty (Simash may have been in the mountains of southern Luristan). The outstanding event of this period was the virtual conquest of Elam by Shulgi of the 3rd dynasty of Ur (c. 2094 - c. 2047 BCE). Eventually the Elamites rose in rebellion and overthrew the 3rd Ur dynasty, an event long remembered in Mesopotamian dirges and omen texts. About the middle of the 19th century BCE, power in Elam passed to a new dynasty, that of Eparti. The third king of this line, Shirukdukh, was active in various military coalitions against the rising power of Babylon, but Hammurabi (c. 1792 - c. 1750 BCE) was not to be denied, and Elam was crushed in 1764 BCE. The Old Babylon kingdom, however, fell into rapid decline following the death of Hammurabi, and it was not long before the Elamites were able to gain revenge. Kutir-Nahhunte I attacked Samsuiluna (c. 1749 - c. 1712 BCE), Hammurabi's son, and dealt so serious a defeat to the Babylonians that the event was remembered more than 1,000 years later in an inscription of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal. It may be assumed that with this stroke Elam once again gained independence. The end of the Eparti dynasty, which may have come in the late 16th century BCE, is buried in silence. Middle Elamite Period After two centuries for which sources reveal nothing, the Middle Elamite period opened with the rise to power of the Anzanite dynasty, whose homeland probably lay in the mountains northeast of Khuzestan. Political expansion under Khumbannumena (c. 1285 - c. 1266 BCE), the fourth king of this line, proceeded apace, and his successes were commemorated by his assumption of the title "Expander of the Empire." He was succeeded by his son, Untash-Gal (Untash (d) Gal, or Untash-Huban), a contemporary of Shalmaneser I of Assyria (c. 1274 - c. 1245 BCE) and the founder of the city of Dur Untash (modern Chogha Zanbil). In the years immediately following Untash-Gal, Elam increasingly found itself in real or potential conflict with the rising power of Assyria. Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria (c. 1244 - c. 1208 BCE) campaigned in the mountains north of Elam. The Elamites under Kidin-Khutran, second king after Untash-Gal, countered with a successful and devastating raid on Babylonia. In the end, however, Assyrian power seems to have been too great. Tukulti-Ninurta managed to expand, for a brief time, Assyrian control well to the south in Mesopotamia, Kidin-Khutran faded into obscurity, and the Anzanite dynasty came to an end. After a short period of dynastic troubles, the second half of the Middle Elamite period opened with the reign of Shutruk-Nahhunte (c. 1160 BCE). Two equally powerful and two rather less impressive kings followed this founder of a new dynasty, whose home was probably Susa, and in this period Elam became one of the great military powers of the Middle East. Tukulti-Ninurta died about 1208 BC, and Assyria fell into a period of internal weakness and dynastic conflict. Elam was quick to take advantage of this situation by campaigning extensively in the Diyala River area and into the very heart of Mesopotamia. Shutruk-Nahhunte captured Babylon and carried off to Susa the stela on which was inscribed the famous law code of Hammurabi. Shilkhak-In-Shushinak, brother and successor of Shutruk-Nahhunte's eldest son, Kutir-Nahhunte, still anxious to take advantage of Assyrian weakness, campaigned as far north as the area of modern Kirkuk. In Babylonia, however, the 2nd dynasty of Isin led a native revolt against such control as the Elamites had been able to exercise there, and Elamite power in central Mesopotamia was eventually broken. The Elamite military empire began to shrink rapidly. Nebuchadrezzar I of Babylon (c. 1124 - c. 1103 BCE) attacked Elam and was just barely beaten off. A second Babylonian attack succeeded, however, and the whole of Elam was apparently overrun, ending the Middle Elamite period. It is noteworthy that during the Middle Elamite period the old system of succession to, and distribution of, power appears to have broken down. Increasingly, son succeeded father, and less is heard of divided authority within a federated system. This probably reflects an effort to increase the central authority at Susa in order to conduct effective military campaigns abroad and to hold Elamite foreign conquests. The old system of regionalism balanced with federalism must have suffered, and the fraternal, sectional strife that so weakened Elam in the Neo-Elamite period may have had its roots in the centrifugal developments of the 13th and 12th centuries BCE. Neo-Elamite Period A long period of darkness separates the Middle and Neo-Elamite periods. In 742 BCE a certain Huban-nugash is mentioned as king in Elam. The land appears to have been divided into separate principalities, with the central power fairly weak. The next 100 years witnessed the constant attempts of the Elamites to interfere in Mesopotamian affairs, usually in alliance with Babylon, against the constant pressure of Neo-Assyrian expansion. At times they were successful with this policy, both militarily and diplomatically, but on the whole they were forced to give way to increasing Assyrian power. Local Elamite dynastic troubles were from time to time compounded by both Assyrian and Babylonian interference. Meanwhile, the Assyrian army whittled away at Elamite power and influence in Luristan. In time these internal and external pressures resulted in the near total collapse of any meaningful central authority in Elam. In a series of campaigns between 692 and 639 BCE, in an effort to clean up a political and diplomatic mess that had become a chronic headache for the Assyrians, Ashurbanipal's armies utterly destroyed Susa, pulling down buildings, looting, and sowing the land of Elam with salt.  Golden Vase with Winged Monsters Marlik Region, Iran 14th-13th centuries BCE - www.iranchamber.com/history/elamite/elamite.phpAs we can see there's much to say about this Empire. As they reflected the mesopotamian Cultures, and had their own language, that is isolated like Sumerian (but wrote with cuneiform) we should spent them more attention. The main focus was always on mesopotamian cultures, that is legit, but if it comes to the topic about mesopotamian cultures, Elamites are one of my favorites. There is even still tons of material for archeological expeditions. I think we should discuss about this. Why is Elam a topic, that is not that popular? Is it because they have been a danger for mesopotamian cultures since the beginning, or because of the political situation in iran ? I want them to bring them more attention so i started this thread, to talk about their Culture, Religion, and Language. |

|

|

|

Elam

May 8, 2013 13:51:01 GMT -5

Post by sheshki on May 8, 2013 13:51:01 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Elam

May 11, 2013 8:12:26 GMT -5

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on May 11, 2013 8:12:26 GMT -5

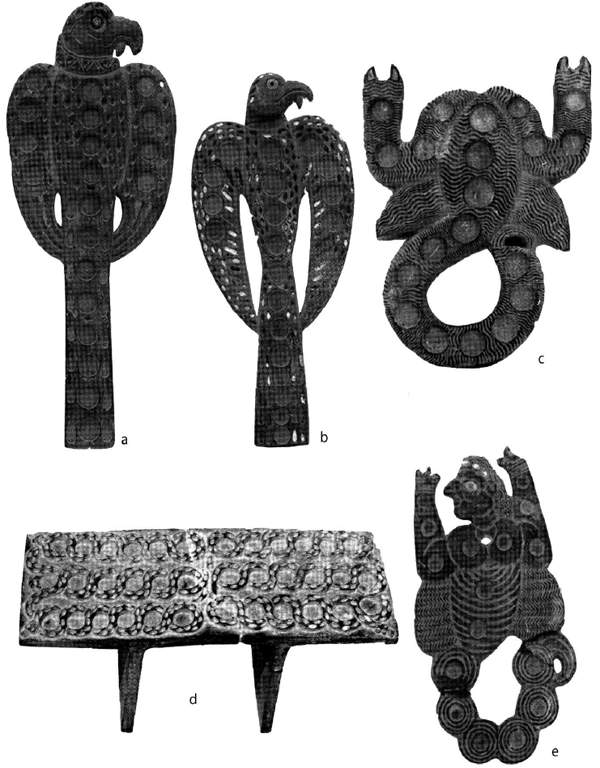

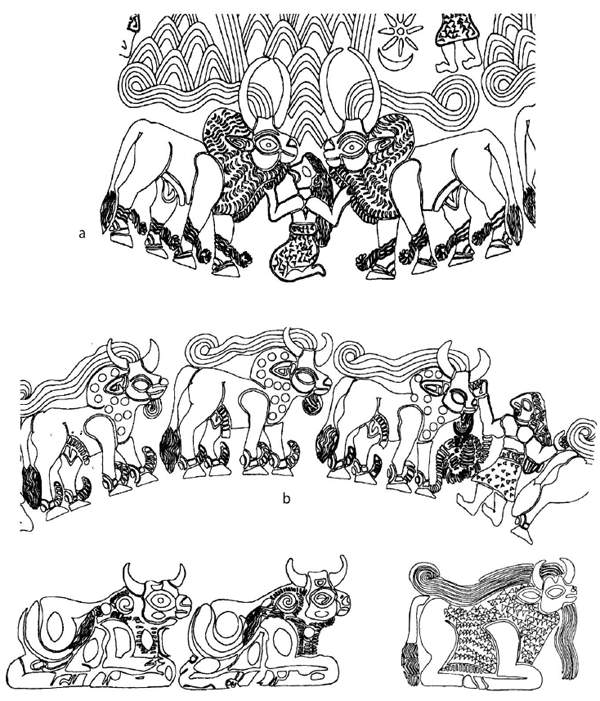

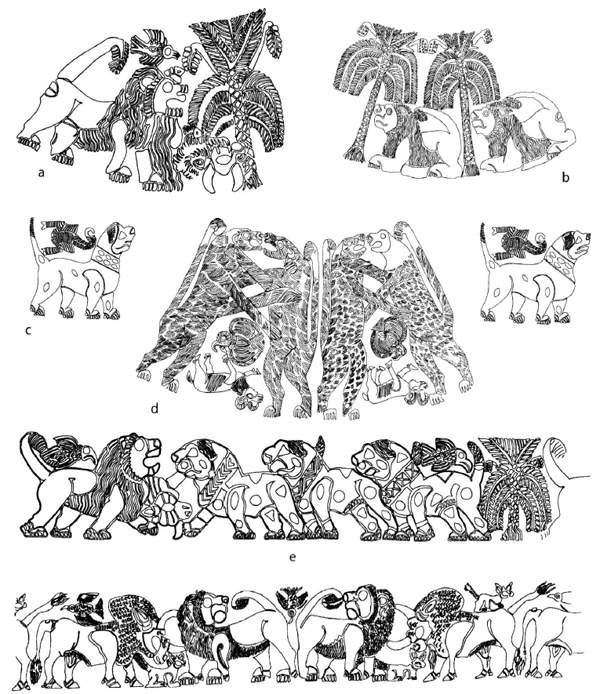

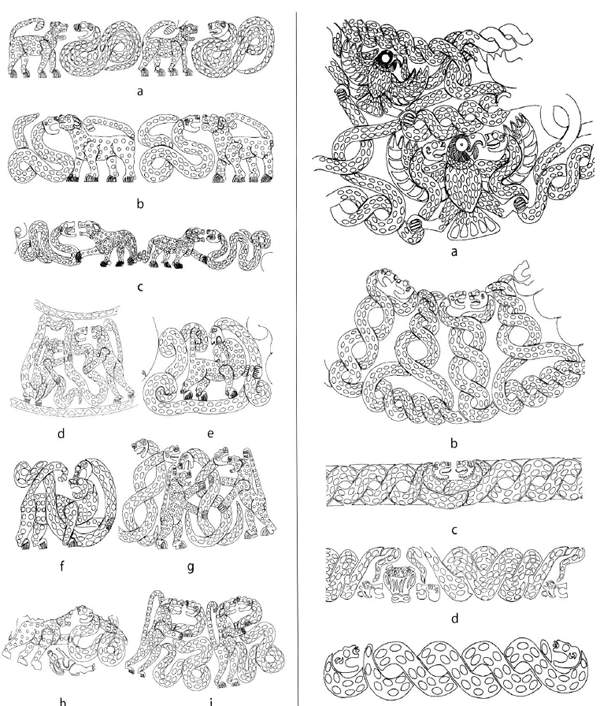

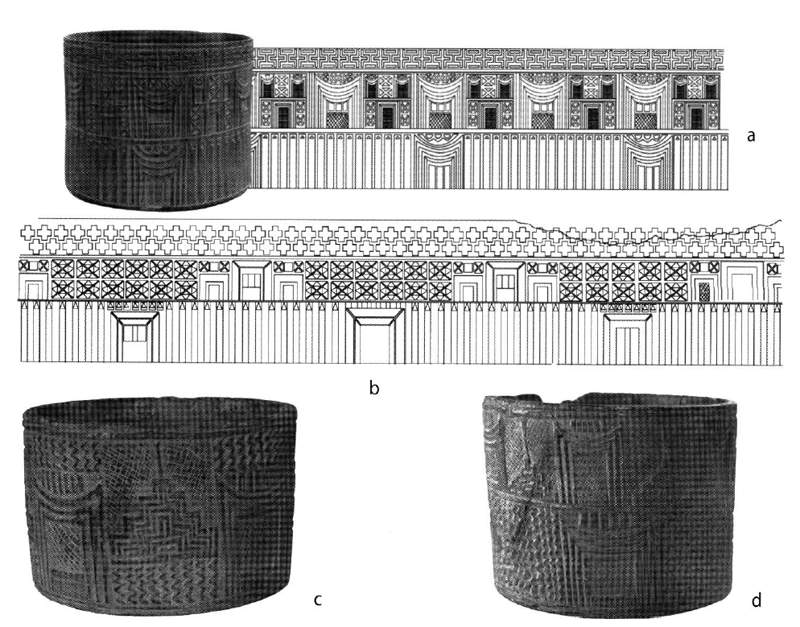

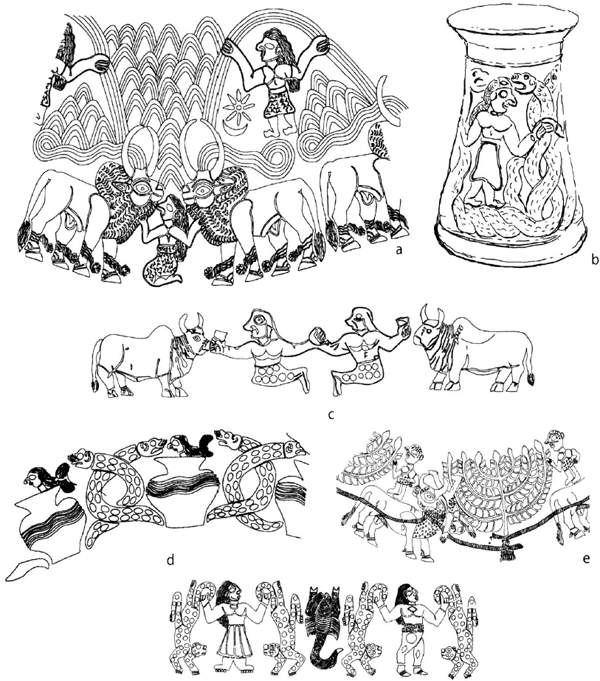

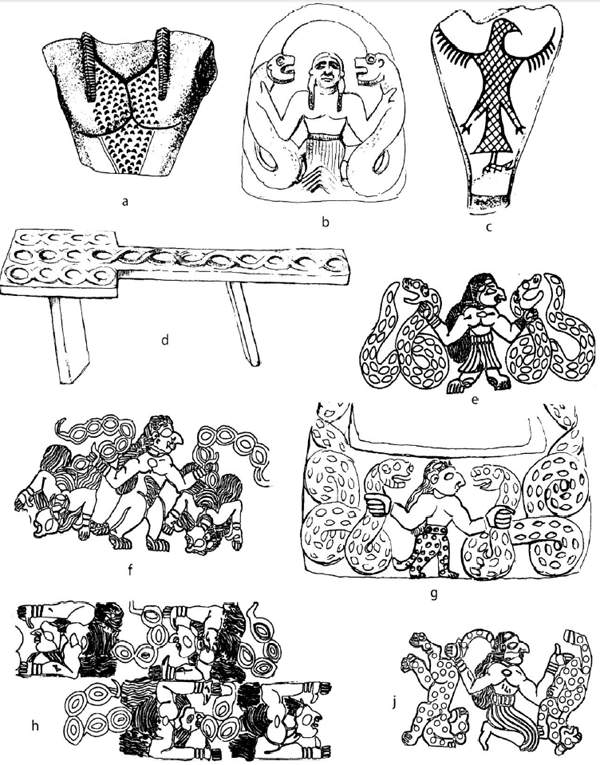

Wow - awesome thread!  Thanks very much for contributing asakku, you're absolutely right in saying that Elam is under studied and generally under considered in the field. There is the occasional scholar who will dedicate their career to Elam but they are pretty rare. They are important for Mesopotamian studies and contributed to the demise of numerous Mesopotamian dynasties. Thanks for your addition Sheshki  Lots of snake motifs, possibly 2 scorpion gods, and one looks like a temple to me. |

|

|

|

Elam

May 12, 2013 7:11:58 GMT -5

Post by sheshki on May 12, 2013 7:11:58 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Elam

May 12, 2013 7:35:29 GMT -5

Post by sheshki on May 12, 2013 7:35:29 GMT -5

Also of interest for this topic is The Elamite Cylinder Seal Corpus, c.3500 - 1000 BC, the doctoral thesis of Karen Jane Roach The ancient region of Elam (southwestern Iran) has produced a significant assemblage of cylinder seals across a considerable chronological span. Unlike the glyptic material from the related and neighbouring region Mesopotamia, the Elamite cylinder seals have not previously been studied in detailed reference to one another, nor has there been an established paradigm of stylistic development articulated. This study addresses this lacuna by compiling all the published cylinder seals from Elam (as defined here, thus incorporating the historical provinces of Khuzistan, Luristan and Fars), from their earliest appearance (c.3500 BC), throughout the era of their typological dominance (over stamp seals, thus this study departs c.1000 BC). This compilation is presented in the Elamite Cylinder Seal Catalogue (Volume II), and is annotated and described through the annunciation of eighteen chronologically defined developmental styles (with another two non-chronological type classifications and four miscellaneous groups). Through the further analysis of this data, including the newly formulated and articulated styles, several facets and problems of Elamite glyptic material have been addressed (and thus the reliance upon assumed similarity in type and function with the Mesopotamian glyptic material is abandoned). These problems particularly pertain to the function of cylinder seals in Elam and the type and form of the Elamite-Mesopotamian glyptic interaction. In regards to function, a standard administrative function can be discerned, though of varying types and forms across the region and the period of study. Other, non-standard, symbolic glyptic functions can also be demonstrated in the Corpus, including the apparent proliferation of a form known as the ‘votive’ seal, perhaps a specifically Elamite form. The analysis of the style type (whether ‘Elamite’, ‘Mesopotamian Related’ or ‘Shared Elamite-Mesopotamian’), in association with their relative geographical and chronological distribution, has also enabled the discussion of the nature of Elamite-Mesopotamian glyptic interaction, and thereby the constitution of Elamite civilisation (especially in regards to Mesopotamian cultural impact and influence, and thus the testing of several previously presented paradigms [Amiet 1979a; 1979b; Miroschedji 2003]). hdl.handle.net/2123/5352 |

|

|

|

Elam

May 12, 2013 7:49:17 GMT -5

Post by sheshki on May 12, 2013 7:49:17 GMT -5

A short article in german by G.J.Selz '''ELAM' UND 'SUMER'" - SKIZZE EINER NACHBARSCHAFT

NACH INSCHRIFTLICHEN QUELLEN

DER VORSARGONISCHEN ZEITge.tt/7dV4MRg/v/0?c |

|

|

|

Elam

May 12, 2013 8:03:57 GMT -5

Post by sheshki on May 12, 2013 8:03:57 GMT -5

Another article by G.J.Selz Irano-Sumerica from the "Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes" from 2001 ge.tt/45zCPRg/v/0?c |

|

asakku

dubĝal (scribes assistent)

Posts: 51

|

Elam

May 24, 2013 6:48:44 GMT -5

Post by asakku on May 24, 2013 6:48:44 GMT -5

Hehe, Selz is my professor, but as i asked him stuff about Elamites he is not very in the mood to talk about. He should really have recommended me his article.

What do you guys think why theres so much few people in this study field? Is it so hard to get to Iran and a digging permission ? I mean Elamites are same important like the ancient people in the levant, and we know about them millions of data more.

|

|

|

|

Elam

Aug 22, 2013 16:09:24 GMT -5

Post by ummia-inim-gina on Aug 22, 2013 16:09:24 GMT -5

This is a really cool thread. I recall Marc Van De Mieroop spending a fair amount of time discussing Elam in “King Hammurabi of Babylon” (Blackwell 1998). There is a chapter dedicated to the significance of Hammurabi’s war with Elam. Note that is during the beginning of the Old Babylonian period that Van De Mieroop is specifically referring to here:

“ To the east of Babylonia, across the Tigris river and the large marshes along its course, lay the ancient land of Elam. It included a wide territory stretching from the Tigris to the highlands of modern-day Fars, some 700 kilometers to the south-east. Elam's western part, governed from the ancient city of Susa, was a lowland watered by several rivers, an environment similar to Babylonia; its eastern part, governed from the city of Anshan, was in the highlands of the Zagros mountains with high mountain peaks and narrow valleys. This duality influenced the political structure of the country in a way that is not fully clear to us. The was a supreme ruler of the entire state of Elam, who bore the ancient title of sukkalmah, borrowed from Babylonia. Very prominent next to him was the man in charge of Susa, the western half of the state, who bore the lesser title of sukkal. The latter had a great deal of independence including in international affairs where he could represent the entire country. In the days of Hammurabi, a man named Siwe-palar-huppak was the supreme ruler of Elam; the sukkal of Susa was Kudu-zulush. Both played active roles in Babylonian affairs.

Because of its dominance in the mountains and its location between Babylonia and regions further east, Elam was the source of some highly desired materials which were absent in Mesopotamia itself. It controlled one the few trade routes used to import tin, crucial for the manufacture of bronze tools and weapons, and lapis lazuli, a dark blue stone that was highly prized for the production of jewelry. Both were mined in the mountains further east in Iran and Afghanistan. Other materials such as hard stone and wood were also brought from Elam into Babylonia for the building of temples and palaces, the manufactures of statues and so on. Elam was, if anything, a wealthier state than the Babylonian principalities.

From its earliest days, some 1,200 years before Hammurabi. Elam had been in close contact with Babylonia, without really having been part of the system of states in that area. At times contacts were very intense, often at the initiative of Babylonian states. In the twenty-first centaury, for example, the kingdom of Ur had conquered Elam and ruled it though governors. Because of its size and wealth Elam was able to field impressive armies and regularly chose to mount invasions of the Mesopotamian lowlands, precipitating political changes there. For example, its campaign around the year 200 terminated the Ur dynasty that rules Elam some decades earlier. The state seems to have preferred to keep its distance from Mesopotamia, however. Sometimes it gave support to Mesopotamian rulers, but it did not attempt to occupy territory. In 1781, for example, it had sent troops to Shamshi-Adad to help him in his campaign against mountain people living in the Zagros, but Elam withdrew immediately afterwards. While Elam did not hold Mesopotamian territory, the kings there seem to have acknowledged the sukkalmah as a very important ruler whose authority supersedes their own. When the quarreled, they hoped for the latter's support to enforce their claims.

This situation was suddenly changed in 1767…”

He then goes into the specific details of the following war between Elam and Mesopotamia.

|

|

|

|

Elam

Aug 22, 2013 16:16:06 GMT -5

Post by ummia-inim-gina on Aug 22, 2013 16:16:06 GMT -5

This has inspired me to discover "The Archeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State" by D.T. Potts (Cambridge University Press 1999). I have loved everything I have read from Potts in the past so I am pretty stoked about reading it. For some reason Potts did not include this title on his Academia.edu profile.

|

|

|

|

Elam

Aug 23, 2013 15:34:24 GMT -5

Post by ummia-inim-gina on Aug 23, 2013 15:34:24 GMT -5

Notes from "The Archeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State" by D.T. Potts (Cambridge University Press 1999)

Chapter one: Elam What, When, Where?

- This chapter deals with the etymology of the name Elam, the chronology of Elam and finally Elam's geographic boarders.

- What: Mesopotamian scribes wrote Elam's name with the sumerogram NIM meaning 'high' which was often accompanied by the determiner KI meaning 'land, country'. The Akkadian form was KUR Elammatum or 'land of Elam'. It was not until the 18th centuary that the name apears in the Elamite language as hal hatamti or just halamti. Walther Hinz suggested this term is composed of hal 'land' ' + tamt 'gracious lord' but it is more likely that Akkadian Elamtu derives from the Elamite Halamti.

"The late appearance of an 'indigenous' name for Elam in Elamite sources and the possibility that Elam might even be a loan word from another language may seem bizarre, but throughout history people and regions have been identified by names other than those which they and their inhabitants themselves used, and comparable examples of what could be termed 'imposed ethnicity' abound in the more recent past." Potts then goes on giving numerous examples of cultures taking on names other cultures have given them.

"One thing is, in any case, certain. The available written sources which pre-date the 18th century BCE give absolutely no indication that the diverse groups inhabiting the Iranian Zagros and plateau regions ever identified themselves by a common term as all embracing as Elam. Dozens of names of regions and population groups attested in late third millennium sources (principally in the Ur III period,2100-200) give us a good impression of the heterogeneity of the native peoples of western Iran, all of whom were simply subsumed under the Sumerian rubric NIM and the Akkadian term KUR Elammatum. Nor did the peoples of there diverse regions speak a common language which, for the lack of an indigenous term, we may call Elamite. Judging by personal names in cuneiform sources, the linguistic make-up of south western Iran was heterogeneous and the language we call Elamite was but one of a number of languages spoken in the highlands east of Mesopotamia. Yet it is not the preponderance of Sumerian, Akkadian and Amorite personal names in texts from Susa, a product of long periods of political and cultural dependency and the widespread use of Akkadian, which justifies our speaking of linguistic heterogeneity in southwestern Iran. Rather, it is the plethora of indigenous, non-Elamite languages attested to mainly by the extant corpus of Iranian [geographically, not linguistically] personal names in Mesopotamian cuneiform sources. Individuals are known from Anshan, Shimashki, Zabshali, Marhashi, Sapum, Harshi, Shig(i)rish, Zitanu, Itnigi and Kimash with names which cannot be etymologized as Elamite."

- When: The is no evidence of the use of the sign NIM to refer to Elam before around 2600 BCE While most scholars cite the Assyrian conquest of Susa as the ending point in Elamite history some scholars cite Elamite influences through the Achaemenid, Seleucid and Parthian periods.

- Where: "In 1667 an East India Company agent names Samuel Flower made the first copies of Cuneiform signs at the Persian Achaemenid city of Persepolis and at nearby Maqsh-i Rustam. Later, it was realized that some of these belonged to the Elamite version of a trilingual inscription in Old Persian, the Babylonian dialect of Akkadian and Elamite. Even if the signs were not yet recognized as Elamite, their copies could be said to represent the first tangible evidence of Elam to have been found outside the pages of the bible. It took more than a century however before Carsten Niebuhr recognized in 1778 that the Persian inscriptions were written in three different languages. Following this realization it became conventional to refer to the Elamite column as the 'second type' of Achaemenid inscriptions, and to designate the language represented by it as Elamite, Susian or Scythian.

A very different notion, emphasizing the distinction between Elam and Susiana, i.e. the district of Susa, can be found, however, in other sources. After describing Susis [Susiana] and an adjacent part of Babylonia, the Greek geographer Strabo wrote, 'Above both on the north and towards the east, lie the countries of the Elymaei and the Paraetaceni, who are predatory peoples and rely on the ruggedness of their mountains'. Thus it is clear the Elymais [the land of the Elymaei, as the Elamites were called in the last centenaries BCE], and Susiana were viewed by Strabo as two different geographic regions. Moreover, although later Jewish writters, such as Sa'adya Gaon [c AD 985] and Benjamin if Tudela [AD 1169] followed the book of Daniel in equating Kuzistan with Elam, the Talmud scrupulously distinguished lowland Be Huzae, or Khuzistan, from Elam.

In the early 1970s inscribed bricks were discovered at the archaeological site of Tal-i Malyan near Shiraz in the highlands of the Fars province which proved that it was the ancient city of Anshan. That led, several years later, to a complete revision of thinking on the location of Elam, spearheaded by French scholar F. Vallat, who argued that the center of Elam lay at Anshan and in the highlands around it, and not at Susa in lowland Khuzistan. Tje periodic political incorporation of the lowlands, and the importance of the city of Susa, had given the impression to the authors of Daniel and Esther that Elam was centered around the site and coterminous with Khuzistan. The preponderance of inscriptions written in Akkadian at Susa, with largely Semetic personal names, suggested to Callat the Elam was centered in the highlands, not in lowland Susiana. One could even suggest that ancient observers had applied the pars pro toto principle when it came to the use of Elam in the Bible, whereby a name which had originally designated only an area around Anshan in Dars came to be used for a geographically much more extensive state which held sway over areas well outside the original Elamite homeland. In order to distinguish between these two Elams, one might even be tempted to use terms like Elam Minor [for the original Elamite homeland in Fars] and Elam Major [for a wider state, which sometimes approached the statues of an empire, created by the Elamites.]

In fact, this would be wrong, and it is equally misleading to suggest that Elam meant the highland of Fars with its capital city Anshan. For as outlined above, Elam is not an Iranian term and had no relationship to the conception which the peoples of highland Iran had themselves. They were Anshanites, Marhashians, Shimashkians, Zabshalians, Sherihumians, Awanites, etc. That Anshan played a lead role in political affairs of the various highland groups inhabiting southwestern Iran is clear. but to argue that Anshan is coterminous with Elam is a construct imposed from without on the peoples of the southwestern highlands of the Zagros mountain range, the coast of Fars and the alluvial plain drained by the Karun-KArkheh river system. For although cuneiform sources often distinguish Susians, i.e. the inhabitants of Susa, Anshanites, this in no way contradicts the notion that, from the Mesopotamian perspective, the easterners - lowlanders and highlanders alike - were all Elamites in the direction of Susa and beyond."

Conclusion: Potts reiterates that in the case of Elam, we are dealing with a notion imposed by Mesopotamian scribes. He then talks about how Elam is both a name and a concept that changed over time.

|

|

|

|

Elam

Aug 26, 2013 5:55:54 GMT -5

Post by sheshki on Aug 26, 2013 5:55:54 GMT -5

Ummia, thanks for the interesting notes. I just checked "Civilizations of the Ancient Near East" by Sasson and will put stuff up later. There is quite a lot of information in there.

|

|

|

|

Elam

Aug 27, 2013 11:59:20 GMT -5

Post by ummia-inim-gina on Aug 27, 2013 11:59:20 GMT -5

Chapter Two: Environment, Climate and Resources

"The approximate geographic boundaries of Elam are set out in this chapter and the topographic and environmental zones within those boundaries are describes. The reader is introduced to the climate, rainfall and hydrology of the relevant portions of Fars, Khuzustan and Luristan in southwestern Iran. Evidence for differences between climate of the past and that of the present is examined and in that context the possibility of anthropogenic changes to the Elamite landscape is raised. Finally the animal, mineral and vegetable resources of the region are surveyed, showing just what earlier inhabitants of southwestern Iran had at their disposal."

I am recurrently finding that Potts seems to share my passion for charts, lists and tables. There is a nice table in this chapter designed to show the reader which animals there is evidence of at archeological sites in the region. Animals included on this table includes: hedge hogs, hares, rufescent pika (I had to look that one up, we certainly don't have any pika here in Florida), mice, rats,wolves, jackals, foxes, hyenas, wild cats, leopards, lynxes, brown bears, badgers, weasels, polecats, beavers, wild horses, boars, aurochs, gazelle, goats, onagers, sheep, deer, cattle, gerbils, dogs, pigs, turtles, mallards, storks, ducks, geese, eagles, cranes, herons, hawks, partridges, crows and cormorants.

A table of mineral attested to in historical texts includes: alabaster, amber, antimony, bezoar, bitumun, borax, carnellion, chlorite, chromite, cobalt, copper, coral, diamond, erythrite, gold,

A table of cultivated plants includes: 2-row hulled Barley, 6-row hulled Barley, 6-row naked Barley, emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, bread wheat, lentils and wild oats.

A table of aromatics includes: asafoetida, bdellium, galbanum, labdanum, olibanum, opoponax, sarcocollaand scammony.

The chapter concludes with a table labeled "Han's Wulff's list of useful timber... compiled from conversations with wood working craftsmen and peasants and archeological attested tree species from excavated sites in Iran." This table includes: acacia, maple, silk tree, alder, bitter almond, sweet almond, almond, mountain almond, box tree, nicker tree, sapan wood, common beech, original beech, chestnut, cedar, nettle tree, judas tree, lemon, orange, sebestrens tree, dogwood, cornel tree, hazel wood, manna tree, cypress, sissoo tree, rosewood, ebony, persimmon, sorb, briar, beech, fig, indian fig, ash, logwood, walnut, laurel, mango, margosa, medlar, mulberry, black mulberry, olive, ironwood. smooth almoind, date-palm, pine, Persian turpentine tree, pistachio, white turpintine. plane tree, white poplar, green poplar, poplar, black poplar, mesquite, cherry and myrobalan,

|

|

|

|

Elam

Aug 28, 2013 13:08:11 GMT -5

Post by ummia-inim-gina on Aug 28, 2013 13:08:11 GMT -5

I have been trying to read up on the correlation of Anshan being the same region as Awan. I see it referenced in many places on the internet (Wikipedia, amateur run historical and archeological websites, etc.) quite often that some “some scholars” have put this idea forth, however the with one exception that I will cut and paste below, I cannot find the names of any such scholars that promote this idea within the academic community. Many sources simply say the location of Awan was north of Susa and remains unknown to us. The below article was written by a J. Hansman back in 1985:

ANSHAN

(or ANZAN), the name of an important Elamite region in western Fārs and of its chief city.

ANSHAN (or ANZAN), the name of an important Elamite region in western Fārs and of its chief city. Akkadian and Sumerian texts of the late third millennium B.C. first attest the land of Anshan. Elamite rulers of the second millennium B.C. traditionally took the title King of Anzan and Shushan (Susa), Anzan being the usual Elamite rendering of Anshan. By the middle of the first millennium B.C. Anshan had become the homeland of the Achaemenid Persians.

During recent years the country and city of Anshan have been associated by various writers with different parts of south Iran. In 1970 an extensive archeological site called Malīān, located on the Dašt-e Bayżā in western Fārs (ca. 36 km northwest of Shiraz) was proposed as being that of the lost city (Hansman, “Elamites, Achaemenians,” pp. 111-24). Several years later brick fragments showing inscriptions in Elamite cuneiform and collected on the site in 1971 and 1972 were found to bear parts of a dedication, proclaimed by an Elamite king of the late second millennium B.C., for a temple described as being in Anshan (Reiner, “The location of Anšan”). Moreover, a number of economic administrative texts excavated at Malīān in 1972 and thereafter attest Anzan, apparently as the location where the texts were written (Carter and Stolper, Expedition, pp. 37-39). These findings would seem to support the suggested identification of Malīān as the site of the ancient city of Anshan.

The earliest Elamite dynasty of which we have record was founded by a certain Peli around 2,500 B.C. in a place called Awan (Scheil, “Dynasties e′lamites,”). But the earliest extant historical reference to Elamite Anshan is given in a text of Manishtusu, a son and second successor of the Sumerian king Sargon of Agade (r. 2,334-2,279 B.C.). Manishtusu tells of resubjugating Anshan after a local ruler there revolted from the empire created by Sargon (Barton, Royal Inscriptions, pp. 128-30). From this we may deduce that Anshan in south Iran was numbered amongst the conquests of Sargon.

A later ruler in Agade, Naram-Sin (2,255-29 B.C.), concluded a treaty of alliance with Khita the ninth king of Awan (König, Königsinschriften no. 2; Cameron, Early Iran, p. 34). The dynasty of Awan thereafter ends with the fall of Khita’s successor Kutil-Inshaushink around 2,220 B.C. At about this same period Gudea, a ruler of Lagash in Mesopotamia, claims to have conquered the city of Anshan in Elam (Barton, Royal Inscriptions, p. 184). It is of interest that Awan is mentioned only once in sources dated later than this, whereas Anshan receives frequent mention, and it is possible that the country of Anshan, in part, may have included the territories of Awan (Hansman, “Elamites, Achaemenians,” pp. 101-02).

Soon after the fall of Awan and Gudea’s capture of the city of Anshan, a new Elamite dynasty rose in the district of Simashki, which has been located in the region of modern Isfahan (Herzfeld, The Persian Empire, pp. 179-80). At this period the Sumerians seem to have maintained some measure of political control at the Elamite city of Susa in present Ḵūzestān and also at Anshan in Fārs. Shulgi (2,095-2,048 B.C.), a ruler of the third dynasty of Ur, married one of his daughters to the ishasha or governor of Anshan (Thureau-Dangin, Sumer. Akkad. Königsinschriften, p. 230); Shulgi also claimed to have laid waste to Anshan (ibid., pp. 231-37). A temporary peace was apparently established when Shu-Sin, son and successor of Shulgi, like his father, gave a daughter in marriage to a governor of Anshan (Virolleaud, “Quelques textes,” p. 384). Thereafter, in about 2,021 B.C., when Ibbi-Sin had succeeded to the throne of Ur, the king of Simashki occupied the land of Awan and Susa in Elam. By 2,017 B.C. Ibbi-Sin had regained much of these territories (Legrain, “Business Documents,” no. 1421); but his success proved only temporary, for within a few years the Elamites had waged a successful military campaign against Ur. After his defeat, the last king of Ur, Ibbi-Sin, was carried off to Anshan together with a statue of the Sumerian moon-god Nanna (Falkenstein, “Die Ibbisin-klage,” pp. 379, 383). Several decades later Gimil-ilishu, second king of Isin brought back Nanna, the God of Ur, from Anshan (Gadd and Legrain, Royal Inscriptions I, no. 100). Still later in about 1,928 B.C., Gungunum, fifth king of Larsa, boasts of military victories in Anshan (Matous, “Chronologie,” pp. 304f.).

The sources show that Anshan had been an important Elamite political center during the last half of the third millennium B.C. Archeological excavations at Malīān would seem to support this assessment. The site is surrounded by a rectangular wall of mud-brick construction, now much eroded, which measures approximately 1 km by 0.8 km. Cultural deposits within the enclosure rise to a height of from 4 to 6 meters (Sumner, “Excavations,” p. 158). Surface surveys of the pottery remains indicate that at least one third of the ancient settlement there (30 to 50 hectares) was occupied from the late fourth millennium B.C. to the latter part of the third millennium B.C. (ibid., pp. 160, 167). The distribution of later pottery suggests that the major occupation at Malīān (some 130 hectares) occurred during the latter centuries of the third millennium and continued into the early centuries of the second millennium B.C. (ibid., pp. 160, 173). This is the period when Anshan is given prominent notice in the cuneiform texts.

The last mention of Anshan in a Mesopotamian source for over 1,300 years is given in the text of Gungurum (ca. 1,928 B.C.) referred to above. Political instability at home had apparently weakened the control which successive Mesopotamian states maintained from time to time over the affairs of south Iran, and a new line of Elamite kings was eventually able to reestablish local rule in their own country. The founder of this new dynasty, Epart (ca. 1,890 B.C.), was also the first known Elamite leader to call himself King of Anzan and Susa (Scheil, “Documents,” p. 1). References to Anshan during the remaining centuries of the second millennium B.C. are attested only in inscriptions and texts of the successive Elamite dynasties of this period.

The heir of Epart in Elam was Shilhakha (ca. 1,940-1,870 B.C.) who styled himself, in addition to king, sukkal-maḫ or grand regent, a Sumerian appellation. During this period the title sukkal or regent of Elam and Simashki and sukkal of Susa are also commonly used (Cameron, Early Iran, pp. 71-72). The sons of the ruling sukkal-maḫ normally filled the office of the two sukkal, though inscriptions show that the sukkal-maḫ on occasion would hold all three titles. However, throughout the approximately 300-year rule of the Eparti dynasty, there is no record of a sukkal of Anshan. This could mean that Anshan consisted at that time of a district subject entirely to the jurisdiction of the sukkal-maḫ though it has been suggested that the sukkal-maḫ and the sukkal of Susa were both resident in the city of Susa. A relationship of this sort in the same town could have caused political tension (Hinz, Elam, p. 5). Indeed, any decree of the Elamite king which might apply to the political district of Susa required ratification by the sukkal of Susa. Yet the case for Susa as the Elamite capital of this period would seem to be the most plausible. Anshan is hardly mentioned in Elamite texts during the whole of the Eparti dynasty except as used in the conventional title of the sukkal-maḫ. A political decline of the older capital is perhaps implicit. This suggestion would appear to be supported by the indications of the archeological survey curried out at Malīān. These show that with the disappearance of the Kaftari sequence of pottery there during the early second millennium B.C., the distribution of the succeeding Qaleh ware on the site is greatly reduced from that of the Kaftari (Sumner, “Excavations,” p. 160). This would seem to indicate that the city of Anshan at Malīān was very severely depopulated during the first third of the second millennium B.C.

Whereas the city of Susa does not appear to have been a major political center during the ascendancy of the Elamite dynasties of Awan and Simashki, archeological excavations at Susa show that it was certainly to become so with the rise of Epart and his successors in Elam. A number of inscriptions found at Susa attest to the building activities undertaken there by different sukkal-maḫ and by various sukkal of Susa. The extensive excavations made by Ghirshman in the “Ville Royale” at Susa have shown that much of this very large quarter of the ancient city was first built upon in the earlier second millennium B.C. (“Susa Campagne,” pp. 4-12). This evidence would seem to support the possibility that the main political center of Elam may have been moved from its traditional location at Anshan to Susa within the period associated with the expansion at the latter site.

In about 1,595 B.C. Kassite and allied invaders from the north overran the kingdom of Babylonia in southern Mesopotamia. But cuneiform texts continue to mention Elamite rulers until the final quarter of the sixteenth century B.C. We do not know whether these later governments in southwestern Iran were subject to the Kassite alliance or, indeed, if the Kassites eventually put an end to the house of Epart. Whatever the case, after about 1,520 B.C. we have no further record of the Elamites for over 200 years.

An apparently independent Elamite dynasty reappears suddenly on the historical scene during the last half of the fourteenth century B.C. Attat-kittash (r. 1,310-1,300 B.C.) is the earliest known ruler of this new line to assume the old title King of Anzan and Susa.

No foundation or rebuilding dedications of Attat-kittash or of his immediate successor Humban-numena (1,300-1,275 B.C.) have been found at Susa, nor are inscriptions or other texts known from the dynastic predecessors of the earlier king. But inscriptions of Untash-napirisha (1,275-1,240 B.C.), son and successor of Humban-numena, are found at Susa and also at the religious center of Dur-Untash (now Čoḡā Zanbīl) located 30 km to the southeast of Susa. The absence of any significant inscriptions of the father of Untash-napirisha at Susa or elsewhere in Ḵūzestān, prompted Labat to suggest that the capital of Humban-numena may have been situated in the province of Anzan (Labat, “Elam,” p. 8). This possibility may gain support from the fact that only at the site of Līān located on the Bushire peninsula in southern Fārs have inscribed bricks of Humban-numena been recovered (König, “Königsinschriften,” no. 58).

If we are to entertain the theory of Labat, the finding of only sparse archeological remains of the corresponding period of occupation at Malīān would seem to indicate that the main seat of government was not then located at the city of Anshan. However, beaker-shaped jars found at Malīān are closely similar to vessels dating from the latter quarter of the second millennium B.C. and excavated at Susa. Inscribed bricks of the Elamite king Hutelutush-Inshushinak (1,120-1,110 B.C.) have also been recovered at Malīān (Reiner). The evidence would suggest that Anshan and Susa were politically and culturally linked at this period, but that Anshan was then little more than an outpost community of the eastern Elamite territories subject to the kings then resident at Susa.

The invasion of Elamite territories (ca. 1,110 B.C.) by Nebuchadrezzer I of Babylon (Thompson, “Astrologers of Nineveh,” no. 200, rev. 5), marked the effective end of Elam as an independent power for nearly 300 years. We do not again hear of the Elamites until 821 B.C. when they are found allied with the Chaldeans against the Assyrian king Shamshi-Adad V (Luckenbill, Ancient Records I, no. 726). Although political unity was apparently not maintained in Elam during at least a part of these intervening “dark” centuries, local chieftains must have preserved some control in areas where they traditionally held authority. It has been suggested by Cameron (Early Iran, p. 156) that local rule would possibly have remained strongest in the more remote eastern quarters of the Elamite territories, i.e., the region of modern Fārs now identified as Anshan. Yet, even if this were so and in spite of their isolation from the troublesome Mesopotamian invaders, the inhabitants of Anshan Fārs were eventually to suffer new intrusions by Iranian migrants moving down from the north. Whether or not the coming of the Iranians caused the divided provinces of Elam to support the rise of a new centralized authority in southwest Iran is a question which cannot be presently answered. But whatever the circumstances, in abort 742 B.C. Humban-nikash I became king of a revived Elamite federation (Luckenbill, Ancient Records II, no. 84).

A nephew, Shutruk-Nahhunte II (r. 717-699 B.C.), succeeded Humban-nikash and took the old title Great King of Anzan and Susa (Scheil in Mémoires, no. 84). Thereafter the Chaldeans of southern Mesopotamia became allied with Shutruk-Nahhunte against both Sargon II and Sennacherib of Assyria. But the alliances proved ineffective, for in this period the Assyrians invaded and held much of southern Mesopotamia. The next Elamite king, Halludush-Inshushinak (r. 699-93 B.C.), invaded Babylonia and temporarily forced the Assyrians from parts of that country, but Sennacherib eventually retook most of these territories. Meanwhile, Halludush-Inshushinak was deposed in Elam and replaced by his son Kudur-Nahhunte (r. 693-92 B.C.). With this change of leadership no Elamite head of state is known to have assumed the ancient royal title King of Anzan and Susa (Cameron, Early Iran, pp. 158-65), an omission which may suggest a loss to the Elamites of at least the area of Anzan/Anshan either by Kudur-Nahhunte or by his immediate predecessor.

After his reconquest of Babylonia, Sennacherib invaded the Elamite lands which lay to the north of Susa. This forced Kudur-Nahhunte to seek refuge in the mountains of Hidalu in Eastern Ḵūzestān and he was eventually replaced as king by Humban-numena (r. 692-87 B.C.) who renewed the old political alliance with Babylonia. The new king also sought military assistance from a number of neighboring districts, including the lands of Anzan and Parsuash (Luckenbill, Ancient Records II, no. 252). It is of special interest to note that in these late attestations Anzan is treated as a separate territory not subject to centralized Elamite authority. What happened in Anzan at this period is bound up with its political and territorial relationships with Parsua, Parsuash, and Parsamish/Parsuwash, and with the Assyrian empire. To understand these associations better, we should consider the location of Parsua and that of the similarly named Parsuash.

The earliest reference to the land of Parsua is given in an Assyrian text of the 9th century B.C. Recent studies would locate this district in the vicinity of Kermānšāh in western Iran (Levine, “Geographical Studies,” pp. 105-13). The same area is identified as Parsuash in inscriptions of Sargon II (721-05 B.C.); these show it to have become a province of the Assyrian empire (see Hansman, “Elamites, Achaemenians,” p. 107, n. 49). It is this Parsuash which presumably rebelled from Assyria and became an ally of both Elamites and Babylonians during the battle fought with the Assyrians at Halule in Mesopotamia (ca. 692 B.C.). Sennacherib claims a major victory over the allied forces in this encounter. Babylonian texts record a more inconclusive result (Cameron, Early Iran, p. 166).

The political unification of Elam seems to have largely disintegrated following the reign of Humban-numena when rival claimants to the central leadership apparently seized control in various parts of the old domains. Some attempts were made to reform the traditional Elamite alliance, notably by Tempet-Humban-Inshushinak (r. 668-53 B.C.) of Susa. But he was defeated by an army of Ashurbanipal, and several districts in Elam which had been overrun were thereafter placed in the control of local chiefs whose support the Assyrians had relied upon (Piepkorn, Historical Prism, pp. 70f.). Such loyalties were not to last, however, for a year later Humban-nikash III, vassal governor in the Elamite district of Madaktu, supported a new uprising in Babylonia against the Assyrians. The rebel Elamite suffered defeat by Assyrian forces at Der and fled to the mountainous district of Hidalu to seek aid from there and from the people of neighboring Parsumash (Waterman, Royal Correspondence II, pp. 410-12; Hansman, “Elamites, Achaemenians,” p. 108). But a revolt in part of Elam at this time caused the fall of Humban-nikash. He was succeed by Tammarit (r. 651-40 B.C.), who continued local resistance against Assyria. Tammarit urged the people of Hidalu and the adjoining district of Parsumash to support his cause, apparently with little result. By 649 B.C. most of the Elamite lands up to the borders of Parsumash had been overrun by the Assyrians (Waterman, op. cit., pp. 300-03; Cameron, Early Iran, pp. 190-93). Although the Elamites seem to have regained a degree of local autonomy in succeeding years, later Assyrian and Achaemenid advances finally put an end to independent Elam.

An Assyrian text relating to the destruction of Elam by Ashurbanipal mentions a king of Parsuwash named Kurash (Weidner, “Nachricht,” p. 4). This Kurash is recognized as Cyrus I of the Achaemenid line, who offered submission to Ashurbanipal and sent his son to Nineveh as a testimony of good faith. With this reference the House of Achaemenes first enters the historical record.

In a Babylonian text Cyrus II (the Great) gives his grandfather Cyrus I the title “Great King of Anshan” (Prichard, Near Eastern Texts, p. 316). It therefore would seem that the first Cyrus was ruler of the former Elamite province of Anshan/Anzan in Fārs and also political chief in Parsuwash. The two lands are certainly identical. Parsuwash/Parsumash would be Assyrian renderings of Old Persian Pārsa, which relates specifically to the province of Fārs, and is not to be confused with the earlier attested toponym Parsuash located in the region of Kermānšāh (Hansman, op. cit., pp. 108-09). At the same time Anshan remained the traditional name in southern Mesopotamia for the region of northern Fārs.

In one passage the Chronicle of Nabonidus, the last king of Babylonia (556-39 B.C.), refers to Cyrus II as King of Anshan; in a further entry Cyrus is called King in Parsu (Smith, Babylonian Texts, pp. 100f.), an Akkadian rendering of Old Persian Pārsa. We may therefore understand, as in the case of earlier references to Anshan and to Parsuwash, that Anshan was also considered at this later period a part of the province now called Fārs (Hansman, op. cit., p. 109, n. 70). The replacement of Anshan as the local name of that province would have occurred much earlier, when the Achaemenid Persians transferred the ethnic name of their nation, Pārsa, to their new homeland in the south. The toponym Anshan is attested only in the Elamite version of the Behistun inscription where it is identified as a non-specific location in Pārsa/Fārs (Cameron, “Old Persian Text,” p. 50).

See also Achaemenid Dynasty; Elam.

Bibliography:

G. Barton, The RoyalInscriptions ofSumerandAkkad, New Haven, 1929.

G. Cameron, “The Old Persian Text of the Behistun Inscription,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 5, 1951.

Idem, Historyof Early Iran, Chicago, 1936.

E. Carter and M. Stolper, Expedition, University of Pennsylvania, Winter 1976, pp. 33-42.

A. Falkenstein, “Die Ibbisin-Klage,” Die Welt des Orients 1, 1947-52.

C. Gadd and L. Legrain, RoyalInscriptions: Ur Excavation Texts I, London, 1928.

R. Ghuirshman, “Susa Campagne de l’hiver,” Arts Asiatiques 15, 1967, pp. 4-12.

J. Hansman, “Elamites, Achaemenians and Anshan,” Iran 10, 1972, pp. 101-24.

E. Herzfeld, The Persian Empire, Wiesbaden, 1969.

W. Hinz, The Lost World of Elam, London, 1972.

F. König, Die Elamischen Königsinschriften, Graz, 1965.

R. Labat, “Elam c. 1600-1200 B.C.,” CAH3, fasc. 16.

L. Legrain, “Business Documents of the Third Dynasty of Ur,” Ur Excavation Texts III, London, 1928.

L. D. Levine, “Geographical Studies in the Neo-Assyrian Zagros II,” Iran 12, 1974, pp. 105-13.

D. Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria, 2 vols., Chicago, 1927.

L. Matous, “Zur Chronologie der Geschichte von Larsa bis zum Einfall der Elamiter,” Archiv für Orientforschung 20, 1952.

A. Piepkorn, HistoricalPrismInscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Chicago, 1933.

J. Prichard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts, Princeton, 1953.

E. Reiner, “The Location of Anšan,” RA 67, 1973, pp. 57-62.

V. Scheil, Me′moires de la De′le′gation en Perse 5, 1904.

Idem, “Documents et arguments,” RA 26, 1929, p. 1.

Idem, “Dynasties e′lamites d’Awan et de Simaš,” ibid., 28, 1931, pp. 1-3.

S. Smith, Babylonian Historical Texts, London, 1924, pp. 100f.

W. Sumner, “Excavations at Tall-i Malyan, 1971-72,” Iran 12, 1974, pp. 155-80.

R. C. Thompson, Reports of the Astrologers of Nineveh and Babylon, London, 1900.

F. Thureau-Dangin, Die Sumerischen und Akkadischen Königsinschriften, Leipzig, 1902.

C. Virolleaud, “Quelques textes cunéiformes ine′dits,” ZA 19, 1905-06, p. 384.

L. Waterman, Royal Correspondence of the Assyrian Empire II, Ann Arbor, 1930.

E. Weidner, “Die älteste Nachricht über das persische Königshaus,” Archiv für Orientforschung 7, 1931.

(J. Hansman)

Originally Published: December 15, 1985

Last Updated: August 5, 2011

This article is available in print.

Vol. II, Fasc. 1, pp. 103-107

|

|

|

|

Elam

Aug 30, 2013 4:32:14 GMT -5

Post by sheshki on Aug 30, 2013 4:32:14 GMT -5

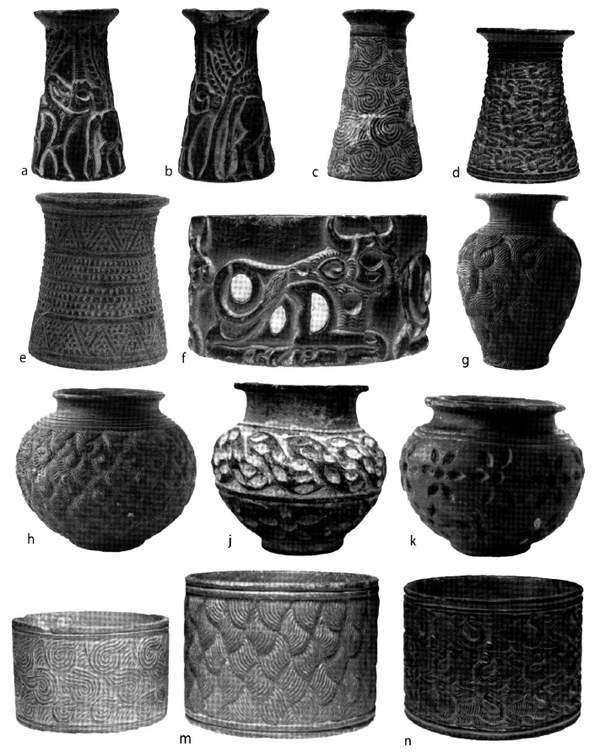

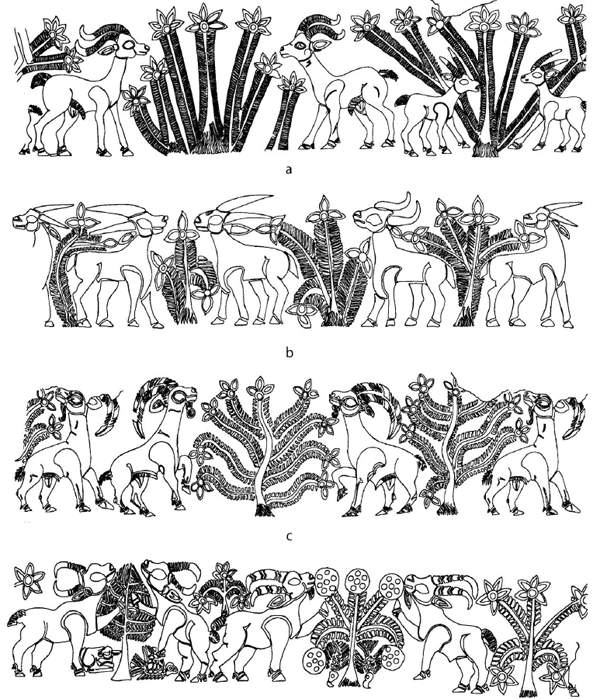

Nice publication from the MET. "The ancient city of Susa (biblical Shushan) lay at the edge of the Iranian plateau, not far from the great cities of Mesopotamia. A strategically located and vital center, Susa absorbed diverse influences and underwent great political fluctuations during the several thousand years of its history. When French archaeologists began to excavate its site in the nineteenth century, the astonishing abundance of finds greatly expanded our understanding of the ancient Near East. The artifacts were taken to Paris through diplomatic agreement and became a centerpiece of the Louvre's great collection of Near Eastern antiquities. These works are rarely loaned, but a remarkable selection that includes many undisputed masterpieces, brought to The Metropolitan Museum of Art for exhibition, is presented in this comprehensive publication. Susa was settled about 4000 B.C. and has yielded striking pottery finds from that prehistoric period. A rich production followed of objects for daily use, ritual, and luxury living, finely carved in various materials or fashioned of clay. Monumental sculpture was made in stone or bronze, and dramatic friezes were composed of brilliantly glazed bricks. Among the discoveries are tiny, intricately carved cylinder seals and splendid jewelry. Clay balls marked with symbols offer fascinating testimony to the very beginnings of writing; clay tablets from later periods bearing inscriptions in cuneiform record political history, literature, business transactions, and mathematical calculations." ... -----> Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre |

|

|

|

Elam

Aug 30, 2013 18:43:19 GMT -5

Post by sheshki on Aug 30, 2013 18:43:19 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Elam

Aug 31, 2013 0:18:59 GMT -5

Post by ummia-inim-gina on Aug 31, 2013 0:18:59 GMT -5

That is a great link sheshki!

|

|

|

|

Elam

Sept 5, 2013 21:29:02 GMT -5

Post by ummia-inim-gina on Sept 5, 2013 21:29:02 GMT -5

Notes from "The Archeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State" by D.T. Potts (Cambridge University Press 1999)

Chapter Three: The immediate precursors of Elam

"The approach taken in this book has been to look at two of the cores areas of later Elamite activity - central Fars and Khuzistan, particularly the sites pf Tal-i Bakun, Tal-i Malyan and Susa - beginning in the later fifth millennium BCE. The justification for this is not a firm belief that the peoples of these areas can be justifiably considered ancestors of the Elamites. Rather, it is because questions which arise in the study of Elam when it first emerges in the historical record of the third millennium BCE need to be addressed in the context of arguments made concerning, for instance, the original peopling of the site of Susa, or the derivation of the earliest writing system used in the region and its relationship to later written Elamite [so-called Linear Elamite]. And Because of the existence of a considerable body of literature devoted to the 'proto-Elamites', even if it is argued below that this is a misnomer, it is necessary to look at certain aspects of the late fourth millennium in Fars and Khuzistan. Since the broad conclusion is that we are not justified in assuming a link between proto-Elamite and later Elamite culture, it is unnecessary to review everything we know about the late fourth millennium at Susa, for example. Rather, only those categories of material culture are examined which bear directly on the question of whether or not the inhabitants of Susa and Fars c. 3000 BCE can already be considered Elamites."

The Origins of Susa: The Susa I period.

"In describing the genesis of the great urban centre of Uruk in southern Mesopotamia H.J. Nissen stressed that it was originally composed of two discrete areas, identified in the cuneiform sources as Kullaba and Eanna, which were only joined into a single entity towards the end of the fourth millennium BCE, and finally circumvallated several centuries later in Early Dynstic I [c. 2900] times. Susa presents us with a somewhat analogous situation, at least in its earliest phase of occupation.

Although G. Dolifus has suggested that Susa may have been a "city of little hamlets" and not a continuously occupied 15-18 ha. area as has often been assumed, this is not quite accurate. The only evidence in Susa earliest period, which we shall call Susa I times, occurs in two discrete areas which early Frecnch excavators referred to as 'Acropole' or acropolis and the 'Apadana mound"

"Apart from these two areas, the rest of Susa [e.g. the so-called 'Ville Royale', the 'Donjon' and the 'Ville des Artisans'] was apparently unoccupied im the site's earliest phase of settlement."

" The date of Susa's foundation is unclear but the earliest C14 determination from the Susa I levels on the Acropole falls between 4395 and 3955 cal. BCE while the latest date from the period can be placed between 3680 and 3490 cal. BCE."

"It has been suggested that the original stock of the Susian population came from many of the surrounding villages which were abandoned as a prelude to Susa's foundation and that the burning of at least a portion of the site of Choga Mish may have had something to so with the foundation of Susa, possibly as Hole has suggested, 'a deliberate attempt to reestablish some kind of a centre and vacate the area of a previous one.' Whatever the raison d' etre behind Susa's foundation, and it may have been very mundane indeed, the site's subsequent development was soon distinguished by a number of architectural developments which would seem to exceed the scope of activities normally associated with village life."

|

|

|

|

Elam

May 4, 2015 4:26:23 GMT -5

Post by hukkana on May 4, 2015 4:26:23 GMT -5

I'm going to go over this thread in detail in just a bit.

But yes I am very interested in the topic, have been for years, I have managed to assemble online a few papers on the subject, as well as the extensive Archeology of Elam and the Elamite Onomasticon which both are great sources of information.

It is rather odd how little attention seems to be given to the topic, even in the matter of inscriptions. I find some refferences to royal inscriptions, but practically none of them are analysed or cited, at least as far as I could find, despite Mesopotamian inscriptions of the earlier, same and later periods being examined in detail.

|

|

|

|

Elam

May 16, 2015 13:25:43 GMT -5

Post by mesopotamiankaraite on May 16, 2015 13:25:43 GMT -5

Elam interests me greatly, especially the possibility of an "Elamo-Dravidian" language family, as well as people related to Elamites creating the Indus valley civilization.

|

|

Golden Vase with Winged Monsters

Golden Vase with Winged Monsters Golden Vase with Winged Monsters

Golden Vase with Winged Monsters

Thanks very much for contributing asakku, you're absolutely right in saying that Elam is under studied and generally under considered in the field. There is the occasional scholar who will dedicate their career to Elam but they are pretty rare. They are important for Mesopotamian studies and contributed to the demise of numerous Mesopotamian dynasties.

Thanks very much for contributing asakku, you're absolutely right in saying that Elam is under studied and generally under considered in the field. There is the occasional scholar who will dedicate their career to Elam but they are pretty rare. They are important for Mesopotamian studies and contributed to the demise of numerous Mesopotamian dynasties.