The Incantation Specialist in Mesopotamia (The Āšipu etc.)

Jul 1, 2016 14:58:49 GMT -5

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jul 1, 2016 14:58:49 GMT -5

The Incantation Specialist in Mesopotamia

enenuru: The following is an excerpt from some research I am doing this summer. This excerpt is intended to serve as a brief overview of the historical development of the incantation specialist in Mesopotamian; in later periods this was the professional "exorcist" as the native terminology is often translated into English (somewhat misleadingly). I have provided all relevant footnotes in this post, that are given at the bottom.

1.2.1 The Early Incantation Experts

Our understanding of professional classes in Mesopotamia is often hampered by gaps in the available information, especially in the early period before colophons regularly occur. It was never the intention of specialist literature to specify the relevant functionaries for the sake of posterity, these texts were intended for the initiated. Therefore, it falls to the modern scholar or reader to surmise this information with the aid of (in most cases) sporadic and incidental information. It is clear that the āšipu, first attested in the second millennium, was not the first profession to utilize Mesopotamia’s venerable incantation lore. In the textual records of the third millennium, other functionaries are mentioned in conjunction with the gods of magic and their craft: in Sumerian texts, the gudu4 priest and the išib priest (additionally the abgal priest, not discussed here);1 in Semitic texts, the mašmaššu priest.2

The gudu4 priest is attested in texts dating back to the archaic period. The image of this third millennium Sumerian priest as shaven and naked before the deity, often discussed by scholars, is an image that has become quintessentially Mesopotamian; an early explanation that these cultic rites of nudity and shaving were precautions to ward off lice (possible displeasing to the gods), remains persuasive today.3 The gudu4 covered his shaven head with a ḫili-wig, a ritual wig associated with the profession in numerous literary passages.4 At Ebla, the Akkadian equivalent of the gudu4, the pašīšu, was in charge of cultic rites, of purification and cleanliness and also acted as a sort of page between the temple and the palace.

These gudu4 priests had to be pure as they were in charge of sacrifices, the care and feeding of the gods, as well as lustration rites.5 Scholars have uncovered and translated a small group of Old Babylonian texts dealing with the purification of the gudu4, these texts dealt with his regular ritual at sunrise which included washing and the recitation of incantations.6 Along with 2nd Millennium texts pertaining to the installation of Ereš-Dinger priests at Emar,7 and a first millennium bilingual text known as “the Consecration of a priest of Enlil”, these Old Babylonian incantation texts provide rare descriptive evidence of the purity rites of Mesopotamian priests. It is perhaps less commonly noted that the gudu4 priest is named in several Early Dynastic incantation texts, and again in the Neo-Sumerian incantations. These references associate the priest with Ningirim, an important goddess of incantation literature and exorcism in the third millennium, and may indicate that the priest had exorcistic duties in the early period, in addition to his various cultic roles.8

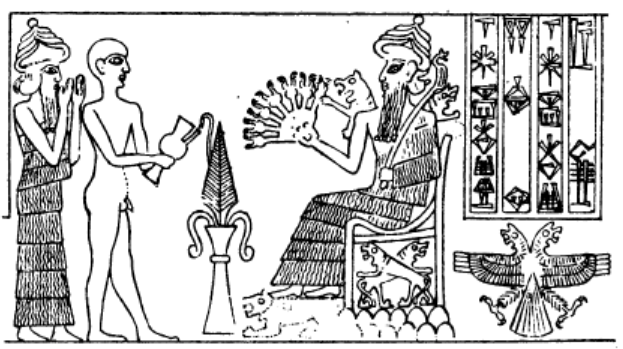

Fig. 1: The išib priest Ur-DUN before Ninĝirsu

(from Westonholz 2013)

(from Westonholz 2013)

Another early functionary, the išib priest, was a high level cultic functionary within the Sumerian temple, as with the gudu4 priest, he was often depicted shaven and nude in the third millennium; see for example the depiction of UR-DUN, an išib priest from ED Lagaš (fig.1).9 In an Old Babylonian incantation recently published by A.R. George, Enki is said to have created the išib-priest, then the god washed the seat, standing place and jars of this priest with rain water from the sky; the texts further explain that this water is the water for cleaning the houses of the gods (thus lustration and holy water, particular in the practice of the išib, is given an etiology). According to J.A. Westenholz, the išib occupied a high office in the ecclesiastical hierarchy, in some places the highest, being responsible for such important rites as the ka-duḫ-ḫa ‘the opening of the mouth’ ceremony, which enlivened the divine statue. The activities of this priest clearly involved cultic lustration and purification rites as well, and išib is often simply translated “purification priest” or “lustration priest” in the literature.10 The prestige of this position is apparent by the fact that the titles išib(-an-na) ‘išib (of the heavens) and išib-an-ki-a (išib of heaven and earth) were used by 3rd and 2nd millennium kings (respectively).11

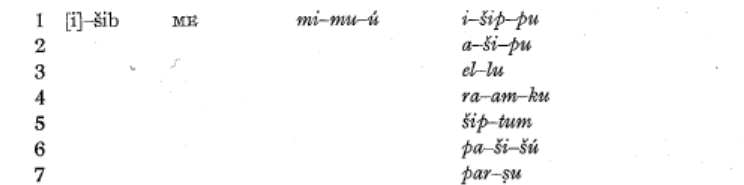

The išib, to, is a potential forerunner of the āšipu. In the Temple Hymns of Enḫe-duanna, the city Murum, belonging to the incantation goddess Ningirima, is praised: “O city, founded upon a dais in the abzu, established for the rites of išib priests, house where incantations of heaven and earth are recited…”12 This profession is also named in several Neo-Sumerian incantations: in Ni 2177 and VAT 6082 Baḫar-enunzaku, an obscure god of magic in the early period, is said to be the king of the išib-craft.13 Interestingly, the išib and the āšipu are associated in ancient tradition by the lexical list MSL 14 223 which also includes several purification priest and the word šiptum (spell) itself:

In terms of the modern understanding the word išib, the values given in MSL 14 223 are reflected in the Pennsylvania Sumerian dictionary (ePSD) entry for išib, which lists “sorcerer; exorcist; (to be) pure; a purification priest; incantation” as possible values, with Akkadian equivalences “ellu; išippu; pašīšu; ramku; āšipu; šiptu.” In fact, there is discussion among scholars as to whether the Sumerian word išib may have its ultimate origin in the Akkadian verb (w)ašāpum “to exorcise,” a verb which derives from the noun āšipu. While these explanations have reached general agreement among scholars, it is held to be problematic since (w)ašapum itself is rarely attested before the Middle Babylonian period.14

1.2.2 The Exorcist in Second Millennium Terminology: the Āšipu and the Mašmaššu

For reasons that will become clear in the following discussion, the āšipu and the mašmaššu must be discussed together as two functionaries who are clearly linked (even as the distinction between them proves difficult to define). Further, they must be distinguished from the gudu4 and the išib as it is clear that neither were priests of the temple per se, but rather they were the lú.mu7.mu7, the “men of incantations”, they were ummānu scholars at the service of the king,15 and as can be seen in texts such as the Diagnostic Handbook SA.GIG, they also treated the sick among the public. One caveat is that the āšipu does move closer to the temple in Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, and is found among the temple staff in Uruk and Sippar; and further, in all periods he could be employed by the temple to carry out important purification rituals and related duties for the cult (as is stated in the Exorcist’s Manual – see 2.2 below). Even so, and despite the shared theocentric approach and techniques of their priestly predecessors, the terms āšipu and mašmaššu are perhaps better understood as referring professions not priests.

The mašmaššu appears already in Archaic and Early Dynastic lexical lists, represented by the Sumerian logogram MAŠ.MAŠ. While the Sumerian logogram is used in both Sumerian and Akkadian texts ranging from early to late periods, it is nonetheless likely that MAŠ.MAŠ was loaned into Sumerian and has its ultimate derivation from the Semitic root mašāšu “to wipe.” As has been previously noted, incantations such as those found in the Šurpu series frequently feature ritual acts involving wiping, such as the wiping of a patient with flour in order to remove his sins.16 A further indication of the Semitic origin of the word is the fact that the mašmaššu occurs first in two Semitic (rather than Sumerian) incantations from the ED period, in association with the incantation goddess Ningirima (in the same period, Sumerian texts were making reference to the gudu4 and išib priests in relation to the same goddess).17 The maš-maš (Sumerian spelling) is attested in Ur III Umma where records state that he was employed using incantation craft to protect the fields.18

The āšipu, for his part, is attested lexically from the Old Babylonian period and in documents from the Middle Assyrian period: some twenty letters from Aššur mention āšipu exorcists by name; their function at this point appears to be in keeping with that known in later periods as namburbi and bīt rimki rituals are already attested in these texts.19 Several contemporary texts from Ḫattuša containing ritual instructions specify the magical expert as the āšipu, spelling the name syllabically and avoiding the usual ambiguities.20 And, indicating the ties between the exorcist and the palace, in Middle Assyrian Law 47 an eyewitness, who was to be interrogated by the king, is sent to the āšipu to swear an oath and make a declaration upon a purification rite.21

A major obstacle to any investigation of the āšipu in early Mesopotamia is that both āšipu and mašmaššu were usually written with the logogram MAŠ.MAŠ. This remains a thorny issue. Are these terms to be understood as synonymous and, if not, what differentiation can be made? Mark Geller makes the following observations which deserve to be quoted at length:23

“The terms ašipu and mašmaššu tend to be mutually exclusive since we hardly ever find a listing with both titles; we have personnel either described as ašipu or described as mašmaššu. Among Middle Assyrian professional titles from the late second millennium BC, we find both ašipu and the logogram maš.maš (= mašmaššu), but not both together; it is either one title or the other (see Jakob 2003: 528f.)…In colophons, very occasionally we find the scribe recorded syllabically as a-ši-pu, but far more common is the logogram (lú.)maš.maš (Hunger 1968: 159, 167f.). The “Haus des Beschwörungspriesters” at Assur is really a household of mašmaššu-exorcists, which is the term used consistently to describe the owners or writers of the tablets from this house (Pedersén 1986: ii, 45f.). The same pattern appears in Neo-Assyrian letters, which always refer to the exorcist with the Sumerian logogram maš.maš, yet the exorcists are said to practice ašipūtu “exorcism.” On the other hand, the so-called Exorcist’s Manual (a list of incipits of magical and medical texts for scholastic purposes) refers to itself as mašmaššūtu, not ašipūtu (Jean 2006: 63).”

This leads Geller to make the suggestion that “āšipu may have been a prestige term of scholarship and literature while mašmaššu comes from the actual parlance of practice and everyday life.”24 Accepting this approach to the problem, it seems expedient to use the term “exorcist” whenever possible, with the understanding that this may reference either the āšipu or the mašmaššu in Mesopotamian terminology (two nuanced terms referring, essentially, to the same profession).

1.2.3 The roles of the Exorcist in Later Mesopotamia

Wisdom in ancient Mesopotamia seems to have implied not philosophy (as with the Greeks) nor piety (as in Job, Proverbs or Ecclesiastes), rather it seems to have implied “skill in cult and magic lore.”25 Of course, as we have just seen, incantation lore was also innately theological, and the appeasement of the gods through purification and incantation might well have been piety, according to the Mesopotamian worldview. In later Mesopotamia, a period noted for its emphasis on theological concerns and the will of the gods, the exorcist experienced a rise in importance and intellectual prestige. The historical origins of this rise are to be found in the decline of the edubba, and its traditional Sumerian literature, sometime in the Kassite period; this prompted, according to P.A. Beaulieu, a “reclassification of intellectual disciplines” within Babylonia, and the shifting of specialized education to the temple, the palace and to the private homes of learned families.26 From the scribal elites of old, higher learning passed to three emerging disciplines, each with a distinctly theological modus operandi: āšipūtu (the craft of the exorcists), kalûtu (the craft of the lamentation priests) and barûtu (the craft of the diviners). These disciplines came to exert “a virtual monopoly on higher learning.”27

From the seventh century on we have invaluable documentation for āšipūtu in the form of the Exorcist’s Manuel (KAR 44), a study guide of sorts listing some 100 titles of compositions that the exorcist was to learn.28 The documents listed were for the student exorcist to “acquire or master” and were labelled explicitly as secret knowledge. Using information mainly found in the Exorcist’s Manuel, Cynthia Jean was able to sketch the roles of the first millennium exorcist as follows:29

• 1. Purely exorcistic rituals: namburbi, šurpu, rituals against witchcraft, rituals associated with dreams, war rituals, rituals to expel demons (Utukkū Lemnūtu, nam-erim-bur-ru -da, šép lemutti);

• 2. Rituals for royalty: king of substitution rituals, purification rituals (The three "bīt rituals");

• 3. Incantation prayers: the šu-íl-la-kam, which are rather a tool, and form part of a more complex ceremony;

• 4. The monthly rituals, the nature and identification of which remain unclear;

• 5. Medicine: diagnosis, prognosis and cures (a field shared with the asû);

• 6. Purification and consecration: foundation rituals, mīš pî, takpertu;

• 7. The technical knowledge necessary for the analysis of a disorder, diagnosis, interpretation and implementation of the solution: a deep knowledge of texts and a knowledge of the stars, stones and plants and the making of materia magica like figurines and amulets.

1. Separating the legendary abgal/apkallu from the concrete proves problematic. In addition to his numerous literary myths and hymns, the abgal is mentioned in two ED incantations (Krebernik 1984 #17, #27E/27l), and is described as the bearer of the lustration water of Ningirim in one Ur III and one OB incantation (PBS 1/2 123 and VS 17,16). Administrative and economic texts attest to the fact that this was a historical profession in the Sumerian period, not simply legendary (see Foxvog, The Sumerian Abgal and Nanše's Carp Actors N.A.B.U 2007/4). However, from the second millennium on, scholars suggest that the profession had disappeared except as a legendary class of sages, and that the occurrences of the term apkallu in later colophon documentation function as honorific titles (Geller 2007 p. 121, 171 n. 16).

2. These observations draw heavily from the Graham Cunningham’s 1997 study of the early incantation literature published as Deliver me from Evil: Mesopotamian Incantation 2500-1500. StPohl 17.

3. Jacobsen 1963, p. 477. The author analyzes the etymology of gudu4 as UH (lice) + IṦIB (anointed) : . This finds some confirmation in the name of the equivalent Akkadian profession, the pašīšu “the anointed one.” Jacobsen’s contention is that the oils themselves, had a bitumen or petroleum base (here he cites a passage from Utukkû Lemnūtu 5, CT CVI pl. 12 ii. 1: uh–tuku (var. tag–ga)-a–mu–dè ià ga-ba-da-an-šéš hé-me-en “Be you a (man who begged:) ‘Plagued with lice as I am (lit. in my lousiness) let me anoint myself with you.’”); Jacobsen’s understanding seems to be reinforced by a lexical text which states that the gudu4 is both pure and anointed (MDP 27 39): ‘gu-dugudu4 = e-el-lu-um ù pá-aš-šu-um’ (Cunningham 1997 p.14). These interpretations are challenged by a new etymological explanation of pašīšu as deriving from Sumerian pa4-šeš, another priest whose name means simply “elder brother.” (Sallaberger – Vuliet RlA 10 p.630)

4. For example, Gilgameš and Huwawa (ETCSL t.1.8.1.5.1 l. 154): “A captured gudug priest restored to his wig of hair!” ; The Lament for Ur (ETCSL t.2.2.2 l.348): “The gudug priest no longer walks in his wig, how is your heart…!”

5. Westenholz 2013, p. 263; Sallaberger – Vuliet RlA 10 p.630.

6. ibid. For a treatment of the texts for the purification of the gudu4, see Farber and Farber 2003.

7. For a treatment of the first millennium material see A. Löhnert 2010, Reconsidering the consecration of priests in ancient Mesopotamia, in H.D. Baker/E. Robson/G. Zólyomi (eds.), Your praise is sweet. A memorial volume presented to Jeremy Allen Black by colleagues, students, and friends. London: British Institute for the Study of Iraq, 183–191

8. Cunningham 1997 p. 14, 65. While one ED text calls the goddess herself a priestess, “the gudu4-priestess Ningirim,” another refers to “the gudu4-priest of Ningirim.” For the original publication of these ED incantations and an excursus on the goddess Ningirim, see M. Krebernik 1984, Die Beschwörung aus Fara und Ebla. (Texte und Studien zur Orientalistik Bd.2), numbers 3 and 24.

9. George 2016, No. 5g, CUSAS 32 p. 58

10.An example which demonstrates the station of this functionary comes from Gudea Cyl. B iv 4, which is translated at ETCSL: “The stone basins set up in the house are like the holy room of the lustration [išib] priest where water never ceases to flow.”

11. Westenholz 2013, p. 258.

12. The Temple Hymns, l. 230-235 (ETCSL t.4.80.1)

13. pace Cunningham 1997, p. 65. The attestation of Baḫar-enunzaku bearing the epithet ‘king of the išib-craft’ in VAT 6082 can be used to restore the partially broken text on Ni 2177 (see Krispijn 2008, Fs. Stol). The god appears in four Ur III incantations altogether (Ni 2177, VAT 6082, HS 2439, HS 1556) and in a ED incantation recently published in CUSUS 32. His importance to early incantation theology has been established by these texts.

14. Geller 2010a p. 43; Sommerfeld 2006, p. 62; Attinger 1993, p. 621: “Il est généralement admis que išib est un emprunt à l'akk. (w)ašipu, ce qui pose toutefois un double problème, chronologique d'une part: (w)ašipu (contrairement à išippu!) n'est pratiquement jamais attesté avant l'ép. mB ; phonétique de l'autre : *išiba (ou *išip/bum) serait de rigueur.” The objection cannot be made on the grounds that (w)ašīpum is never attested in the OB period however, as MSL 12 p.170, an OB lexical list, contains an entry LÚ.MU7.MU7.GÁL = wa-*ši-pu-ú (Jean 2006 p. 26).

15. RlA 10 p.632

16.Jean 2006 p. 21; Geller 2010a p. 44 – the suggestion that mašmaššu is a nominalized form of mašāšu was first made in Livingston 1988 (A note on an epithet of Ea in a recently published creation myth' NABU p.10). However, alternative suggestions exist: CAD suggested that the word is a loan from Sumerian MAŠ.MAŠ, and this suggestion is upheld in Jean 2006 p. 22: “L’équation LÚ.MAŠ.MAŠ est généralment admise: mašmaššu est une akkadisation du sumérian MAŠ.MAŠ.”

17. Cunningham 1997 p.15. The texts in question are published in M. Krebernik 1984, Die Beschwörung aus Fara und Ebla. (Texte und Studien zur Orientalistik Bd.2), numbers 39 and 32.

18. RlA 10 p. 632.

19. For a detailed discussion of the MA evidence, see Jakob 2003, p. 528-535.

20. See Zomer, forthcoming. KUB 29, 58 + 59 + KUB 37, 84: i.30; KUB 4, 17 (+?) 18: r. iv?.3; Iraq 54, pl. XIVc: 32-33

21. Roth 1997, p. 58. This practice may remind one of the unofficial use of the “poison ordeal” of the Middle Ages, whereby Catholics suspected of wrongdoing would be required to undertake communion, under the assumption that they would be damned if guilty or dishonest.

22. Cunningham 1997 p. 16 notes the confusion: “The reading of the logogram remains uncertain: American and English Assyriologists generally prefer to read it as āšipu, German as mašmaššu.”

23. Geller 2010a p. 49

24. Ibid pg. 50; pace Jean 2006 p. 31 who believes that the terms have some hierarchal significance, i.e. one being the assistant to the other.

25. W.G. Lambert, BWL p. 1; Beaulieu 2007 p. 12 relates that āšipūtu and bārûtu are labelled as nēmequ (wisdom) in some colophon material, further, the Catalogue of Texts and Authors “ascribes the entire authorship of āsipūtu and kalûtu to Ea, the god of wisdom.”

26. Beaulieu 2007b p. 11

27. Ibid. p. 17

28. See Geller 2000 242-254; Jean 2006 62-72; Schwemer 2011 p. 421

29. Lenzi 2008 85-90. Interestingly, Lenzi notes that even this very large list of material to be mastered by the student exorcist does not represent all āšipu (fn. 109). He refers the reader to Jean 2006 86-108 and to Bottero 1975 96-116, studies which clearly note exorcistic works not listed in KAR 44.

30. Jean 2006 p. 195-196 (My translation from the French). This sketch can be checked against the summary of the contents of KAR 44 provided in Schwemer 2011 p. 421: i) compositions associated with the temple cult, washing of the mouth rituals and the installation of priests (ll.2-3); ii) compositions for appeasing angry gods (l.4); iii) rites and ceremonies pertaining to kings, performed on behalf of the king (l.5); iv) extensive diagnostic and prognostic series (l.6); v) Sumerian incantations against demons (l.7) vi) purification rites and Sumerian incantations against demons (l.8-10); vii) the purification rituals Bīt Rimki, Bīt Mēseri together with washing of the mouth rituals. (l.11). viii) various rituals against witchcraft and curses; (12-14). ix) Texts to deal with evil dreams, impotency, pregnancy and infants. (l.14-15); x) rituals and incantations against diseases affecting specific body parts (l.16-28); xi) incantations against snake bite, scorpion sting, and sāmānu disease (l.19). xii) Measures for the protections of a man’s house, followed by rituals to ensure acceptance of offerings (l.20); xiii) Ceremonies pertaining to houses, fields, gardens, canals followed by rituals against storm damage and field pests (l. 21-22); xiv) rituals for protection during travels