|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Sept 29, 2007 2:18:10 GMT -5

Thread Orientation: The ETCSL project is well known for providing a large number of Old Babylonian literary compositions in addition a number dating from the UrIII period. The project, and key secondary literature exploring these same texts, have made the exploration of Sumerian literature a reality for many enthusiasts - however a look at the DCSL (Diachronic Corpus of Sumerian Literature) makes it apparent that there is still much more to consider. Due to a lack of access, I personally have little knowledge of the Pre-Sargonic (c. 2800-2350 BC) compositions outlined at the DCSL, but there is alot to look over (click here) I am not yet in a position to articulate the function or literary significance of these texts therefore. Some basic information, The DCSL catalogues 226 Pre-Sargonic compositions of which some 200 are understood to be "UD.GAL.NUN compositions", apparently these are texts written with a certain orthography and are from Abu Salābīkh. This corpus of texts was designated "UD.GAL.NUN" due to the fact that this line occurred frequently throughout the corpus, however Ive yet to be able to read or access any of them. The other 26 Pre-Sargonic compositions consist of different type of hymns, laments or narratives - currently of these the following are available at ETCSL: The instructions of Šuruppag, The Keš temple hymn and perhaps sometime 'A hymn to a deity' (ETCSL 4.33.3 -:" not yet edited as part of the corpus"). There remain a number of literary treasures in this list, all seem considerably in-accessible, but could be of high interest for an understanding of the development of the Sumerian pantheon and its surrounding mythology. Below we can add what glimpse's are obtained of these obscure texts.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Sept 29, 2007 2:26:53 GMT -5

An Enlil fragment:

CDLI : P221771 (Almost pointless)

Translation: Not Obtained

A Note From:

An Akkadian Animal Proverb and the Assyrian Letter ABL 555, by Bendt Alster Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 1989 The American Schools of Oriental Research

Alster reviews the suggestions of H. Vanstiphout as to the significance of the fox in a certain Akkadian poem. In considering Vanstiphouts suggestions, Alster mentions:

"To the evidence cited by Vanstiphout can be added the pre-Sargonic Istanbul fragment shown on the jacket of S.N. Kramer's book From the Tablets of Sumer, and also illustrated in the book itself [Falcon Wing Press, 1956, jacket illustration and p.106 fig 6a.] The text, a myth of Enlil, tells that Ishkur was held back in the Netherworld, from where he apparently was rescued by the fox."

**Addition Nov.12: Alster gets somewhat more descript in a footnote from JCS 1976 pg.17 and adds: "the fox proposes a plan by means of which he must be expected to have been rescued. The fox plays a very similiar role in the later myth of Enki and Ninhursaga. This proves that the idea of the fox as a very clever animal goes back to the beginning of literature."

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Sept 29, 2007 2:35:11 GMT -5

A Ninurta narrative (the Barton cylinder)

CDLI: P222183

Museum number: [CBS 8383]

Translation: Not Obtained

Alster, Bendt. 1976b. On the Earliest Sumerian Literary Tradition. Journal of Cuneiform Studies 28, 109-126.

Alster begins this article by reflecting on some of the conclusions of A. Falkenstein, who concluded that the majority of known literary compositions could not have assumed their final shape before the UrIII period - yet creations like the cylinder inscriptions of Gudea presuppose a long literary activity (if a non-written one.) And Falkenstein "also noted that one of the few pre-Ur III literary compositions known at thattime, the so-called Barton

Cylinder (Barton MBI 1), which he dated to the Akkad dynasty, showed a number of characteristics that recur in all later compositions, such as the grouping in parallel lines and repetitions of entire sections. [SAHG p.19]. While this in itself is hardly surprising, it is perhaps more interesting that he also observed a more specific relationship in that the Cylinders of Gudea repreatedly operate with a poetic formula which has a clear forerunner in the Barton Cylinder. [5] Yet, with reference to the same text, he came to the conclusion that since it differs so much from the later known mythological compositions that practically no connected sense could be gained from it, considerable changes are likely to have occured in the mythological tradition in the Old Babylonian period.

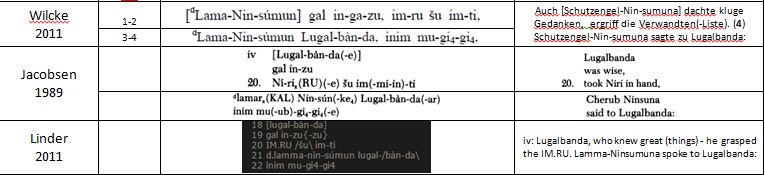

[5] See A. Falkenstein, AnOr 30 183 with n.5. He there referred to Barton MBI 1 xiv (copy "col. iv") 9 = xvii (copy "col.viii") @: gal i3-ga-mu-zu, to Sollberger Corpus EAN. 1 xviii 1 and parallels e2.an.na.tum2-me gal na-ga-mu-zu, and to "Lugalbanda and Enmerker" 50 (see now Cl. Wilck, Das

Lugalbandaepos p.96): lugal.ban3.da gal in-zu gal in-ga-an-tum2-mu "Lugalbanda who is as wise as active." In the Cylinders of Gudea (cf. AnOr 30 183 n.4), the phrase reads: gal mu-zu gal i3-ga-tum2-mu. This very same phrase recurs in the myth "Inanna and Bilulu" 49, with reference to Inanna:

gal mu-un-zu gal in-ga-an-tum2-mu (cf. Th. Jacobsen, JNES 12 174). An Early Dynastic forerunner from Abu Salabikh can now be found in the volume under discussion, No. 327, obv. ii 1: lugal.ban3.da gal.zu6. CRRA 2 19.

edition- Alster, Bendt and Aage Westenholz. 1994. The Barton Cylinder. Acta Sumerologica 16, 15-46.

Handcopy: MBI 1 (= ASJ 16 43-46)

Photo number: MBI pl. 24-28 (= FTS 106 pl. 6)

Object type: Clay cylinder

Provenance: Nippur

Language, writing and usage: Sumerian

Mein Kopf ist schwer

|

|

|

|

Post by madness on Oct 17, 2007 0:27:51 GMT -5

A cosmogonic narrative Museum number: [ AO 4153] Edition from Sjöberg, Åke W. 2002. In the Beginning. In Tzvi Abusch, Riches Hidden in Secret Places: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Memory of Thorkild Jacobsen. Column i 1. [an-e ] 2. [x] muš ha-mu-ni-sig-sig 3. ki-e SAL.HUB 2-na dalla ha-mu-ak-e 4. SAR-am 3 te-me-nam 5. ki-buru 3 a še 3-ma-si Column ii 1. an en nam-šul-le/eš 2 al-gub 2. an ki teš 2-ba šeg 12 an-gi 4-gi 43. u 4-ba en-ki nun-ki nu-se 124. den-lil 2 nu-ti 5. dnin-lil 26. nu-ti Column iii 1. u 4-da im-ma 2. ul-[la] im-m

3. u4 nu-zal-[(zal)]

4. i3-ti nu-e3-e3

Column i

1. [Let An-Heaven . . . ]

2. . . .

3. Let Ki-Earth come forth in (all) her lavishness(?)!

[or: Ki-Earth came forth in (all) her lavishness].

4. She was green (like) a garden, it was cool.

5. The holes in the ground were filled with water.

Column ii

1. An, the En, was standing (there) as a youthful man.

2. An-Heaven and Ki-Earth were "resounding" together.

3. At this time the Enki-and the Nunki-gods did not (yet) live,

4. Enlil did not (yet) live,

5. Ninlil did not (yet) live,

Column iii

1. "Today"( "last (year)," "last (year),"

2. "The remote (time)"( "last (year)," "last (year),"

3. The sunlight was not (yet) shining forth,

4. The moonlight was not (yet) coming forth.

Some points from Sjöberg's commentary that will help to understand this text. I have not included J. J. van Dijk's translations, which are in French, maybe I'll try to Babelfish them later.

Column i

Jacobson translates line 2 as "he bent down (his) head's (radiant) crown" : ag-muš ha-mu-ni-sig-sig. Restoration ag is uncertain though.

Jacobson translates line 3 as "and the earth spread (open) (her) vagina with her left hand." He understood the line as ki-e (a2/šu-)gabu3-na gal4(-la) dalla ha-mu–ak-e. His translation for "spread" is uncertain. He interpreted gal4 as gal4-la, corresponding to "female genitals."

Sjöberg points out that SAL.HUB2 must denote in some way the spouse-to-be of a deity; the Akkadian translation šummuhtu, "the lovely one," may be based on a connotation of sexual attractiveness.

Jacobson has for line 5 "he 'reacted' ('responded') by filling/deciding to fill the holes with the seed (of the rain)."

Column ii

Jacobson has for line 1 "Heaven, the giver of growth, was as redoubtable in his prime (maturity)."

The "conversation" of line 2 probably took place after the separation between Heaven and Earth, which took place u4-ul-la "in the remote day" (cf. ul-[la] in our text iii 2).

Column iii

Jacobson has for lines 1-2 "'today' and 'yesterday' was the same"; "'the morning of time' (i.e. the beginning of time) and 'yesterday' was the same."

However, a different interpretation of u4-da im-ma might be possible: u4 "weather," "sultry weather," "air," and im "wind." This would then be referring to seasons. If this interpretation is correct, the text says that there were no seasons. However, the interpretation of ul then becomes difficult, and it is uncertain whether it might denote a season.

If Jacobson’s interpretation is accurate, these lines conceptualize time before creation as standing still. |

|

|

|

Post by galzugaltumu on Oct 20, 2007 10:11:49 GMT -5

"Tribute"-List

In the DCSL there is also an entry about the so-called Tribute-List. This text is in ATU 3 considered as lexical text. Englund stated in OBO 160/1 that it might be a literal work. There is a new treatment of the text by Niek Veldhuis (Univ. of Berkeley, CA) who interpret this list as a kind of exercise for apprentice scribes. This is very likely and I believe him. He also renamed this list into Word List C. "Tribute" is a mis-interpretation of a later colophon.

Veldhuis, Niek. 2006. How did they Learn Cuneiform? “Tribute/Word List C” as an Elementary Exercise. Pp. 181-200 in Piotr Michalowski and Niek Veldhuis (eds.), Approaches to Sumerian Literature in Honour of Stip (H.L.J. Vanstiphout), Leiden: Brill 2006.

Best wishes,

galzugaltumu

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Oct 30, 2007 17:15:34 GMT -5

Wonderful contribution with the Cosmogonic narrative Madness, I will definitly need to further consider it - and thanks very much for your addition Galzugaltumu, I was drawing a blank about the tribute list though Id thought Id seen something on it somewhere - I think I remember where now! Well it seems the book cited will be as challenging to access for the layman as are many of this quality and focus, though after some browsing I remember Veldhuis does give whats probably an abbreviated -though still revealing- accounting of his views on Word List C at: cuneiform.ucla.edu/dcclt/intro/arch_intro.htmlThis page also serves as a reasonable introduction to the Archaic Lexical Corpus for the ANE layman, who for lack of ATO 3 etc, stands a fair chance of knowing next to nothing about such indefinitely. He gives a partial translation of Word List C, though I dont know from which of the apparently 57 archaic sources it draws from. Also two transliterations of Word list C are viewable at cuneiform.ucla.edu/dcclt/Q000030/xQ000030.htmlI love Pre-Sargonic stuff ;] heading back to the DCSL page.. |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Oct 30, 2007 19:11:17 GMT -5

za3-me hymns:

CDLI: NA

Translation: In Small Part

Robert Biggs in OIP 99 (Oriental Institute Publications) made available for the first time some 515 texts excavated from the site called in modern times Abū Ṣalābīkh. The texts are estimated chronologically to be contemporary with the Fara texts, approx 2600 B.C. Also edited for the first time in this work (I believe partial transliterations are provided) are the za3-me hymns.

Mark E. Cohen JCS 1976:

In an article "The Name Nintinugga with a Note on the Possible Identification of Tell Abu Salābīkh" , Cohen explains an interesting hypothesis as to the identification of the ancient site which in modern times is called Abu Salābīkh. And he makes this assertion based on the za3-me hymns.

Apparently no fragments of these hymns have been found anywhere else, and the author explains the hymns are most similar in structure to 'the Temple Hymns', now a well known composition. The Temple hymns are attributed to Enḫeduanna, daughter of Sargon of Akkad, and Cohen notes the concluding hymn is dedicated to "the e2-a-ga-de3-ki, the temple of A(m)ba in Akkad, the city of the redactor, Enḫeduanna." Thus this hymns final position conveys a place of honor and correlates to the poets own city.

The author points out that in the za3-me hymns, the hymn to the goddess Lisi [dLi8-si4] concludes the text and theorizes that this is the tutelary goddess of ancient Abu Salābīkh. Supporting evidence is that Lisi alone recieves special praise (whereas other deities receive a formulaic DM za3-me, DM priase) and also in this text Lisi is one of three deities to bear the epithet ama, or mother (alongside Nintu and Ningal.)

This goddesses name appears in the Abu Salābīkh god-list directly below dBIL.GA, and Cohen believes that in the Fara period she was an important mother goddess, in the za3-me hymn her city is given as giš-gi ki-du10 or "Giš-gi the good place." Gišgi* then, is the name the author suggests for ancient Abu Salābīkh. According to archaeological evidence, occupation in this city ceased in the ED IIIa period, and so it would follow that the cities tutelary goddess lost her importance, and this accords well with Lisi's later identification with Dingirmah in and in the OB period, position as that deities daughter (thus falling from mother goddess to the status of daughter of a mother goddesss.)

On the Earliest Sumerian Literary Tradition, by Bendt Alster (Journal of Cuneiform Studies 1976)

Alster here provides just the first hymn of the (I believe 26) za3-me hymns, this one dedicated to Enlil:

1. uru an-da mú

2. an-da gú-lá

3. dingir nibru.ki

4. dur.an.ki

5. den.líl kur.gal

6. den.líl en nu:

7. nam.nir

8. en dúg-ga

9. nu-gí -gí

10. LAK 809 nu-LAK 809

11. den.líl a.nun

12. ki mu-gar-gar

13. dingir gal gal

14. zag.me mu-dúg

1. City, grown together with heaven,

2. embracing heaven,

3. god of Nippur,

4. "Bond of heaven and earth"

5. Enlil, "great mountain,"

6. Enlil, lord

7. Nunamnir,

8. whose command

9. is irrevocable

10. whose ... cannot be ...

11. Enlil who placed the Anunna gods

12. below earth,

13. the great gods

14. spoke his praise.

Interestingly, the za3-me hymns have Enlil addressed first rather then Enki as in the Temple Hymns - Enki acutally isnt apparent at all in the earlier hymns which may be relatable to the proximity of Abu Salābīkh (Giš-gi?) to Nippur if anything.

Alster provides a fascinating cosmological commentary on this which Id have to quote in full to do any justice:

"If it is justifiable to translate "who placed the Anunna gods below earth" (line 11-12), there is probably a connections with ideas contained in other early sources. A small Ur III literary text, NBC 11108, describes the world before the seperation of heaven and earth. At that time An, the god of heaven, was "lord" (en), information which could also have been obtained from another early text, Sollberger Corpus Ukg. 15 iii 1, and the "Anunna gods did not walk around (NBC 11108: 12: [...] a.nun-[ke4-n]e nu-um-di-di). No light existed. This stage corresponds to the reign of Ouranos in Hesiod's Theogony. In our sources it was changed by the seperation of heaven and earth, which, according to the Barton Cylinder, happened when the first stroke of lightning occurred in Nippur. A later text, the "Hymn to the Hoe" (UET 6 26 and dupls.), tells that it happened when Enlil hit Dur.an.ki with his hoe, but I would suggest precisely that this hoe of Enlil is a symbol of lightning. At any rate the lightning in this context reminds one of lightning as the attribute of Zeus, and Dur.an.ki, meaning "the bond of heaven and earth," reminds one of the Greek Omphalos in Delphi. It is hinted at in an Early Dynastic hymn, UM 29-16-273 + N 99 iv 7, as "the twisted rope to which heaven is secured" (dur sur an la2-gim). When seen in this context, it is possible that our text hints at the time when Enlil, by separating heaving [sic] and earth, established Dur.an.ki as the navel of the world, and divided the gods in two groups, the gods of the upper world (these are later called the Igigi-gods), and the gods of the lower world, who are the Anunna gods. It is well known that the Anunna gods acted as judges in the nether world, but, admittedly, one must count on the possibility that some Anunna gods belong to the upper world, such as those mentioned in "Lahar* h and Asnan*s" 2, where we probably have to read: u4 an-ne2 an [d]a.nun.na im-tu-de3-es*-a-ba "on the day when the celestial Anunna gods were born by Heaven."

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Apr 13, 2008 1:22:17 GMT -5

Lugalbanda and NinsumunMuseum Number: IM 70263 Cdli: P010263 Translation: Obtained

Edition from " Lugalbanda and Ninsuna" , Thorkild Jacobsen JCS 41, 1989, pp. 69-86 Translation: 1. Cherub Ninsuna was lifting out (baked) "beer bread" confections. Cherub Ninsuna was very shrewd, she stayed awake 5. and lay down at his feed. Wise Lugalbanda passed the arm around Cherub Ninsuna, could not resist kissing (her) on the eyes, 10. could not resist kissing (her) on the mouth, also taught her much love making. Cherub Ninsuna brought grass, melted the frozen grass and spread it; 15. on a pad of lettuce until dawn they slept in Uruaza. Lugalbanda was wise, 20. took Niri in hand, Cherub Ninsuna said to Lugalbanda: "To Uruk, to the en, let me set out with you 25. for the 'tablet of deliveries'." Lugalbanda prostrated himself on the ground before the en, and the en said to Lugalbanda: 30. "Let me look at what you have brought from the mountains, the Anunaki are headed hither, let me have them look at what you have brought from the mountains." 35. Lugalbanda came out into the outer courtyard, neck cutting Niri, noble Niri, reported to the spirit, 40. and the goddess mother of Lugalbanda came out of the hatch. Cherub Ninsuna was quick, sprinkled holy water on the ground, 45. Lugalbanda shuddered. When she had sprinkled water on the ground for the spirit, the goddess mother of Lugalbanda 50. she said: he has brought you a wife from the mountains and has slept with the wife. Mother-in-law, for me, a bride worthy of your son, 55. decree issue, 5 males ... " (text omitted here) Noble Niri whispered to the spirit: "In the outer courtyard, in "The gate that brings myriads' let me take 60. office. To noble Niri the spirit said: (text breaks off) "Line 1: The word Jacobsen translates as "cherub" is in fact the Sumerian dlama(r). His accompanying note reads - dlama(r), Akkadian lamassu or lamassatu, denotes a special kind of guardian angel. It is used throughout the text as an epithet of Ninsuna and it occurs with her name also in the zá-mí hymns OIP 99 48:84, as pointed out by Biggs." Line 20: Ní-rí x(RU) Jacobsen speculates that this item Ni-ri, based on context, may be a weapon, an axe, sword etc, which is personified and said to be of noble birth "seed of a prince." A similar example Shar-ur , Ninurta's animated weapon. Line 39. For comment on "spirit" -(Jacobsens reading of lil(-la) as it appears in the transliteration) refer here to the 'Revisions on Sisig', reply #7, found here

|

|

|

|

Post by madness on Nov 29, 2008 22:35:50 GMT -5

The Barton CylinderCDLI: P222183 Museum number: [ CBS 08383] Transliteration: cdli.ucla.edu/search/result.pt?id_text=P222183Translation: i 1-2 Those days were indeed faraway days. i 3-4 Those nights were indeed faraway nights. i 5-6 Those years were indeed faraway years. i 7 The storm roared, i 8 The lights flashed. i 9 On the sacred area of Nippur i 10 the storm roared, i 11 the lights flashed. i 12-13 Heaven talked with Earth. i 14 Earth talked with Heaven. Lacuna ii 1 With the "Grand-Good-Lady-of-Heaven", ii 2 Enlil's older sister, ii 3 with Ninhursag, ii 4 with the "Grand-Good-Lady-of-Heaven", ii 5 Enlil's older sister, ii 6 with Ninhursag, ii 7 he had intercourse. ii 8 He kissed her. ii 9 The semen of seven twins ii 10 He impregnated into her womb. ii 11-12 Earth held a conversation with the "scorpion": ii 13 "Supreme Divine River, ii 14 'Your little "things" are carrying water". ii 15 For you(?), the god(?) of the river . . . Lacuna iii 2 . . . reached Heaven. iii 3 The "ears" of the poplars swelled. iii 4 "Grape-eyes" were placed among them. iii 5 "White-eyes", "great lights" iii 6 were piled up with them. iii 7 The gudu-priest . . . iii 8 "Mighty . . . , your . . . iii 9 'is being taken away". iii 10 . . . iii 11 the beans . . . iii 12 The gudu-priest like a man of Aratta iii 13 directed it. Lacuna (At this point a passage parallel to v 3-6 may have been included). iv 3-5 Enlil's . . . caused (Enlil) to feel bitterness iv 4 toward Nippur. iv 6-7 He caused Inanna to feel bitterness toward Zabalam. iv 8-9 He caused Enki to feel bitterness toward Abzu. iv 10 Enlil's . . . iv 11 did not provide Nippur with food to eat. iv 12 He did not provide (Nippur) with water to drink. iv 13 His oven(?) in which bread was baked iv 14 contained no baked bread. iv 15 His oven(?) in which bread cooled down iv 16 [contained no] bread cooling down. (Someone speaks to Enlil and gives him an account of what has been told in the last part of column iv). v 2 Enlil . . . to . . . v 3 "The brackish water he . . . v 4 'The brackish water he is holding back. v 5 'Enlil! he . . . v 6 'The brackish water he is holding back. v 7 'Your oven(?), in which bread was baked, v 8 'contains no baked bread. v 9 'Your oven(?), in which bread cooled down, v 10 'contains no bread cooling down. v 11 'Your(?) supreme ox-devouring oven, v 12-13 'its stones(?) he made lie (idle) in(?) the sacred area of Nippur. v 14 'Your supreme bronze . . . v 15 'does not return(?) to(?) . . . vi looks like the conclusion of the preceding speech, addressed to Enlil, although the sequences follow in a different order. (v 3-6 may correspond to the beginning or end of column iv; v 7-10 to iv 13-16; vi . . . 3-4 to iv 3-9). However, another possibility is that this is the end of a separate speech addressed to Ninurta. v [". . . Enlil's . . . caused (you,) (Enlil,) to feel bitterness v 'toward Nippur,] vi 1-2 ['he caused Inanna to feel bitterness toward Zabala,] vi 3-4 'he caused Enki to feel bitterness toward Abzu". vi 5-6 He came out! He came out! vi 7 As the day rose from the night vi 8-9 Ninurta came out! vi 10 As the day rose from the night, vi 11 he dressed his body in a lion's skin. vi 12 With lions' skins vi 13 he garnished himself. vi 14-15 (unintelligible) ... vii, viii, and ix 1-7: No translation is provided here. Note vii 9 and 11: "My mother", and vii 10: "Your young man". viii 12: "Those who enter the place". ix 8 For their children ix 9 the fate was determined. ix 10 For the north wind ix 11 its fate was determined. ix 12-13 "Come, let Azulugal be(?) your life!" ix 14 The shepherd . . . . . . x 9-10 For the . . . wind its fate was determined. x 11 Come! May Enkidu be your friend! x 12 "The wasteland may Enlildu . . . x 14 'for men . . ." . . . xii 4 . . . left Keš. xii 5 [The place] where Enlil eats his bread xii 6 . . . xii 7 Irhan, xii 8 the good one . . . . . . xiii 3 The [pure] Tigris and the [pure] Euphrates xiii 4 Enlil's pure scepter xiii 5 . . . the mountain(?). xiii 6 Let its roots . . . xiii 7 [Let] its top . . . xiii 8 On its side [let] . . . xiii 9 [Let] eggs [be laid] on the ground. . . . xiv 3 . . . multiplied in the mountains. xiv 4 Black bulls multiplied. xiv 5 White bulls multiplied. xiv 6 Reddish bulls multiplied. xiv 7 Dark-red bulls multiplied. xiv 8 Horrible "horse-lions" xiv 9 also multiplied. xiv 10 Mountain horses xiv 11 climbed on top. xiv 12 . . . dwelt. xiv 13 The . . . carried wool. xiv 14 The . . . stags of Ninhursag xiv 15 [multiplied(?)] . . . xv 6 Dabala . . . xv 7 To the temple . . . xv 8 after the birds left it, xv 9 after he has put flour into its sack, xv 10 after he has poured water into its water skin, xv 11 Dabala, who is equally wise (said): xv 12 "To my temple . . . xv 13 'after the birds have left it, xv 14 'after flour has been put into the sack, xv 15 ['after water has been poured into its water skin . . ."] . . . xvi 2 Ninhursag, our "arm"(?), xvi 3 took possession of our precious metal. xvi 4 . . . returned. xvi 5 Our pure container, our . . . container, xvi 6 our man of . . . xvi 9 took possession of xvi 7 the . . . gold, xvi 8 our . . . xvi 10 Two pots . . . xvi 11 poured two . . . xvi 12 Their . . . beloved heart, xvi 13 dispersed beer. xvi 14 Irhan . . . . . . xvii 2 "The pure Tigris and the pure Euphrates, xvii 3 'the pure scepter, my brother, xvii 4 'Enlil, xvii 5 'the man . . . xvii 6 'M[y] son . . . xvii 7 '. . ." xvii 8 Ninhursag xvii 9 put fine antimony, eye-paste(?), and fine oil(?) xvii 10 onto her eyes. xvii 11 She established a seat of honour in Keš(?). xvii 12 Below they(?) carried. xvii 13 Below nobody . . . . . . xviii 3 The temple . . . xviii 4 That day, passing . . . xviii 5 That night, darkening . . . xviii 6 Irhan . . . xviii 7 . . . xviii 8 The temple . . . xviii 9 My child, . . . xix 2 . . . Ešpeš, xix 3 who is equally wise, xix 4 bolted the great gate, xix 5 bound the door with his/her hand, xix 6 and brought . . . down from the sanctuary. xix 7 Irhan . . . . . . xix 11 raised his/her eyes toward heaven xix 12 like a wild boar of the canebrake . . . xx 2 . . . pleasure . . . xx 5 greatly(?) pleasant . . . xx 9 his "place of manhood" xx 10 like . . .

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Mar 22, 2010 18:51:30 GMT -5

On Li9-si4 [/color][/center] A small update on the goddess Lisi (Li 9-si 4), who may well have been the tutelary goddess of ancient Abu Salabikh (see blurb above, october 2007), is that her name also appears in three lamentations from the OB and later periods that M. Cohen translated in his 1989 work, the Canonical Lamentation texts of Ancient Mesopotamia. This is an excellent treatment of Mesopotamia's Balag Lamentations, written in emesal. The first balag lamentations in Cohen's book to mentions Lisi is one with an incipit that translates to "Fashioning Man and Woman" but seems to fall short of actually describing this mythical event itself (unfortunately). However, we have a mentioning of the goddess in the following lines: line 292: mother Baba, the lady of Uruku, line 293: the great mother of Abba, the princely son, line 294: mother Lisi, the lady of Ehurshaba, line 295: the lady Nisaba, the lady Ninibgal, line 296: Umunaba, the lord who rides the ox.... a very similar series of lines appears in another balag lamentation, "Wild Ox": line 168: "mother Lisi, the lady of Ehurshaba" a last mention from a text "Arise! Arise!" contains the line: "mother Lisi, the lady of the Hurshaba". All three lines are essentially the same therefore. The Ehurshaba (spelled gašan-e2-ur5-ša3-ba) seems to be the new information for us here, as we had previously noted the goddess, her probably city (Abu Salabikh) but I don't believe I'd yet seen a name for her sanctuary.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jul 11, 2011 2:13:44 GMT -5

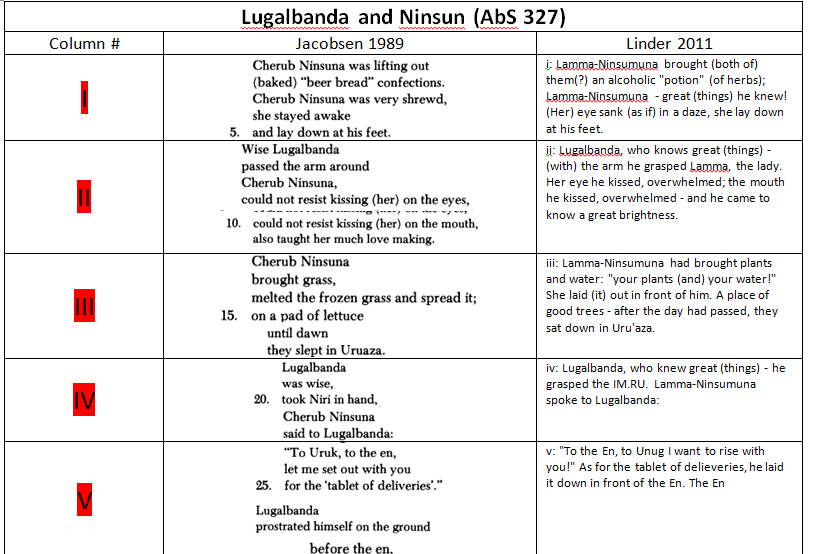

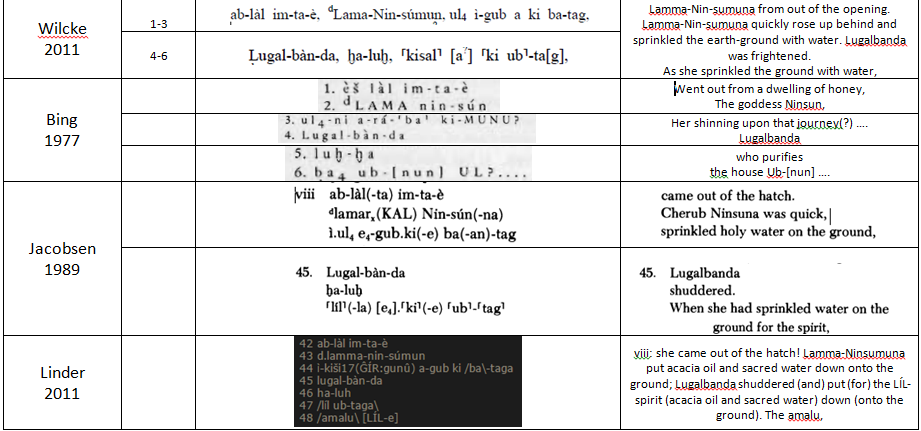

- - 3 Translations of AbS 327 - - Lugalbanda and Ninsuna This text, which we first saw in reply #7 above, as an Presargonic text form Abu Salabikh and was translated originally by Jacobsen in 1989. There exist many unknowns about the reading of the text, it's interpretation and the intriguing religious notions evident, yet elusive within. Today I have the good fortune of being able to compare three separate translations of this text and so I will present them below should anyone be interested on comparing or contrasting. Following the translation I will make a few comments. The text editions below are: A) Translation from: "Lugalbanda and Ninsuna" , Thorkild Jacobsen JCS 41, 1989, pp. 69-86B) Translation unpublished: This translation was kindly submitted by Nadia on the Sisig thread, reply #19. C) Translation from: "The Birth of Gilgamesh in Ancient Mesopotamia Art", Douglas R. Frayne, Bulletin CSMS 34 (1999), pp. 39-49| Row 1 column 1 | Row 2 column 2 | Row 3 column 3 | | Row 2 column 1 | Row 2 column 2 |

| Translation: | A) T. Jacobsen 1989 |

[/i][/td][td] B) N. Linder 2011[/i][/td][td] C) D. Frayne 1999[/i][/td][/tr] [tr][td]lines 1/2[/td][td] Cherub Ninsuna was lifting out (baked) "beer bread" confections.[/td][td]Lamma-Ninsuna - verily she brought the aromatic beer-'matrix'(1)[/td][td]The protective goddess, Ninsuna (Gilgamesh's mother), brought beer-bread (out of the oven).[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 3-5[/td][td]Cherub Ninsuna was very shrewd, she stayed awake and lay down at his feet. [/td][td] Lamma-Ninsuna - she knew great (things). (Her) eye grew tired, at his feet she lay down to rest. [/td][td]The protective goddess, Ninsuna, performed a wise deed. She stayed awake. She lay at his (Lugalbanda's) feet.[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 6-9[/td][td]Wise Lugalbanda passed the arm around Cherub Ninsuna, could not resist kissing (her) on the eyes,[/td][td]Lugalbanda, who knew great (things) - (his) arm was touching the Lamma, the lady; on the eyes he kissed her, overwhelmed[/td][td]Lugalbanda, the wise one, put his arm around the protective goddess, Ninsuna. His kissed her eyes.[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 10/11[/td][td]could not resist kissing (her) on the mouth,also taught her much love making.[/td][td]on the mouth he kissed her, overwhelmed: The day that she learned great things(2). [/td][td]He kissed her mouth. He... her.[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 12/13[/td][td]Cherub Ninsuna brought grass, melted the frozen grass and spread it;[/td][td]Lamma-Ninsuna had brought food: 'Your plant, your water!' She spread it there in front of him.[/td][td][The protective goddess Ninsuna] brought [/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 15-17[/td][td] on a pad of lettuce until dawn they slept in Uruaza.[/td][td]A place (of) various woods ........... they sat down in Uru'aza-[/td][td]In a lettuce(?) patch, until day-break- they rested(?) in Uruaza...[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 18-20[/td][td]Lugalbanda was wise, took Niri in hand,[/td][td]Lugalbanda, who knew great (things) grabbed IM.RU[/td][td][Lugalbanda] performed a wise deed. He took the clay pot in hand.[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 21-25[/td][td]Cherub Ninsuna said to Lugalbanda: "To Uruk, to the en, let me set out with you for the 'tablet of deliveries'."[/td][td]Lamma-Ninsuna spoke to Lugalbanda: "To the En, to Unug I want to rise with you, to the tablet of deliveries!"[/td][td]The protective goddess, Ninsuna, conversed with Lugalbanda: "[...]" "[...]" "[...] at the 'tablet of delieveries'"[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 26-29[/td][td]Lugalbanda prostrated himself on the ground before the en, and the en said to Lugalbanda:[/td][td]Lugalbanda - he kneeled on the bare floor in front of the En, and the En spoke to Lugalbanda:[/td][td]Lugalbanda prostrated himself before the lord [....] The lord conversed with Lugalbanda (saying):[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 30-34[/td][td]"Let me look at what you have brought from the mountains, the Anunaki are headed hither, let me have them look at what you have brought from the mountains."[/td][td]"You brought things from the mountains - I want to marvel at them! The offspring of the nobles are coming hither in a row - things from the mountains you brought, (and) I want to marvel at them!"[/td][td]"Let me examine that which you have brought from the mountain land." The "princely offspring" (= Gilgamesh[?])...[The lord said]: [Let me..] at that which you have brought from the mountain land."[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 35/36[/td][td]Lugalbanda came out into the outer courtyard,[/td][td]Lugalbanda went out into the outer courtyard[/td][td]Lugalbanda went out to the courtyard (of the temple/palace),[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 37-42[/td][td]neck cutting Niri, noble Niri, reported to the spirit, and the goddess mother of Lugalbanda came out of the hatch.[/td][td]IM.RU the neck-cutter, IM.RU the Anunna - he spoke (to) the LÍL-ghost, to the divine mother. The LÍL-ghost, the divine mother came out of the hatch![/td][td]The clay pot... The "princely offspring: (= Gilgamesh[?]) A lil demon [...] [...] ... went out from the window.[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 43-46[/td][td]Cherub Ninsuna was quick, sprinkled holy water on the ground, Lugalbanda shuddered.[/td][td]Posthaste, Lamma-Ninsuna sprinkled the proper water onto the ground. Lugalbanda shuddered - [/td][td]The protective goddess, Ninsuna, quickly poured out an oblation. Lugalbanda shuddered.[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 47-50[/td][td]When she had sprinkled water on the ground for the spirit, the goddess mother of Lugalbanda she said:[/td][td]he touched the LÍL-ghost! The divine mother, she spoke to Lugalbanda:[/td][td]After (Ninsuna) poured a libation, the lil demon... The goddess Ina[nna] conversed with Lugalbanda (saying):[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 51-55[/td][td] he has brought you a wife from the mountains and has slept with the wife. Mother-in-law, for me, a bride worthy of your son, decree issue, 5 males ... "(text omitted here)[/td][td]"You - a wife (you) brought from the mountains! The wife, you have lain (down together) with her!" - "(O) mother-in-law (??) - the husband is a fitting regalia (?!), he is your son (and) the temple of (my) heart!" [......][/td][td]You have brought a wife from the mountain land. (Since) I have no spouse, Let me be your mother-in-law, may your son (Gilgamesh) take counsel with me."[/td][/tr][tr][td]lines 57-61[/td][td]Noble Niri whispered to the spirit: "In the outer courtyard, in "The gate that brings myriads' let me take office. To noble Niri the spirit said: (text breaks off)"[/td][td]IM.RU, the Anunna, whispered to the LÍL-ghost: "(In) the outer courtyard, (by) the Gate which brings Thousands into for me - I want to partake in the Rites!" (To) IM.RU, the Anunna, the LÍL-ghost spoke: [.....]"[/td][td]The "princely offspring" (= Gilgamesh[?]) ... the clay pot.. the lil demon. In the courtyard, at the gate where everything is brought. ... The clay pot, the "princely offspring" ( = Gilgamesh?[?]) ...[/td] [/tr] [/tbody][/table] Comments

So there are a good many peculiarities and mysteries within this text; Jacobsen believes that the text we have preservered is only a part of the whole story, while the beginning and ending, while may allow for a more full understanding, may have been contained on other tablets, so far undiscovered. While the text cannot be expected to yield it's answers any time soon, we could at least proceed by examining some of the concepts.. Lines 21-25: The 'tablet of deliveries' - I am unable to locate other instances of the term that Jacobsen transliterates dub mu-ir10(ra) in anything I have on hand. We notice in line 15-17 that the story begins in Uru'aza. which Frayne understands to be somewhere in Elam to the east; Jacobsen addresses this situation wherein Lugalbanda is, presumably, on his way back to Uruk, very likely, after completing some errand for the en: "The r6le of messenger is traditional with Lugalbanda, who traverses the mountains between Aratta and Uruk as messenger for Enmerkar in Lugalbanda II, and that tribute from outlying areas, gun mada, was collected and brought in by royal messengers is shown by the Ur III text CT 32 19f. vi 14 and 23, which presumably reflects also earlier practice..." This suggestions reminds me very much of Steinkeller's discussion of the possible utility of the Uruk period City seals - that they acted as proof of collection by the varies officials sent by the Urukian administration. Notes on that here. In any case that Lugalbanda may have been acting as such a functionary here is interesting. *******Must break for now. More to follow... A Hymn to dLAMA-SA6-GA, Åke W. Sjöberg

|

|

|

|

Post by nininimzue on Jul 12, 2011 9:24:51 GMT -5

Lugalbanda and Lamma-Ninsumuna; "The Marriage of Lugalbanda" (c) N.Linder 2011 The 2nd Edition: obv. i: 01 d.lamma-nin-súmun agarin5 02 mu-DU.DU 03 [d]lamma-nin-súmun gal in-zu 04 igi mu-lib(LUL) 05 ĝìr mu:na nu ii: 06 /lugal\-bàn-/da\ gal-zu 07 d.lamma-nin-ra 08 á mu-ni-dab 09 igi a-sub5(LAK 672) 10 ka /aš\(A)-sub 11 UD(-)gal in-ga-mu-zu iii: 12 [d.lamma-nin-súmun-ke ú a] 13 /mu\-de(DU) 14 ú-a-za mu-ni-{ba}bárag 15 ki ĝiš-dùg 16 ud en-na zal 17 URUxAZA(PIRIxZA) dúr-šè AL:dúr-dúr iv: 18 [lugal-bàn-da] 19 gal in-zu{-zu} 20 IM.RU /šu\ im-ti 21 d.lamma-nin-súmun lugal-/bàn-da\ 22 inim mu-gi4-gi4 v: 23 [en-ra unug{ki}-šè] 24 [ga-da-zid] 25 dub mu-/DU-è\ 26 lugal-bàn-da 27 en-ra ki mu-na-za 28 en lugal-bàn-/da\ rev. vi: 29 /inim mu-gi4\-gi4 30 níĝ-kur-ta re6-zu 31 u6 ga-dug 32 a-nun si mu-sá-sá 33 níĝ-/kur-\ta [re6-zu] 34 [u6 ga-dug] vii: 35 lugal-bàn-/da\ kisal-bar-šè 36 im-ma-ta-/è\(/UD\:DU) 37 [IM]./RU gú-ku 38 IM.RU a-nun 39 /LÍL šu\ [mu\-ni]-/gi4\ 40 [LÍL]-/amalu\ ([AMA]-INANNA)-[ke4] 41 [lugal-bàn-da-šè] viii: 42 ab-làl im-ta-è 43 d.lamma-nin-súmun 44 ì-kiši17(ĜÍR:gunû) a-gub ki /ba\-taga 45 lugal-bàn-da 46 ha-luh 47 /líl ub-taga\ 48 /amalu\ [LÍL-e] ix: 49 lugal-bàn-da-ra 50 imin mu-/gi4-gi4\ 51 za dam kur-ta mu-de6 52 dam mu-da-nu 53 ú:ÚR ĝidlamX(SAL.NITA) 54 me:/te dumu\-zu 55 šà-dùg inim-ma x: 56 5 NITA [...] /////////// 57' IM.RU /a-nun\ líl mu-za 58' kisal-bar ká-šár ma-lah4 59' /ĝarza\([PA.]/AN\) [šu] /ga\-[ab]-ti 60' IM:/RU\ -/nun\

Translation:

i: Lamma-Ninsumuna brought (both of) them(?) an alcoholic "potion" (of herbs); Lamma-Ninsumuna - great (things) he knew! (Her) eye sank (as if) in a daze, she lay down at his feet.

ii: Lugalbanda, who knows great (things) - (with) the arm he grasped Lamma, the lady. Her eye he kissed, overwhelmed; the mouth he kissed, overwhelmed - and he came to know a great brightness.

iii: Lamma-Ninsumuna had brought plants and water: "your plants (and) your water!" She laid (it) out in front of him. A place of good trees - after the day had passed, they sat down in Uru'aza.

iv: Lugalbanda, who knew great (things) - he grasped the IM.RU. Lamma-Ninsumuna spoke to Lugalbanda:

v: "To the En, to Unug I want to rise with you!" As for the tablet of delieveries, he laid it down in front of the En. The En

vi: spoke to Lugalbanda: "The things which you have brought from the mountain lands - I want to marvel at them! The offspring of nobles are putting them into order; the things which you have brought from the mountain lands - I want to marvel at them!"

vii: Lugalbanda went out into the courtyard. The IM.RU of the gú-ku5r, the IM.RU of the a-nun he gave over to the LÍL-spirit. The LíL-spirit, the amalu - to Lugalbanda

viii: she came out of the hatch! Lamma-Ninsumuna put acacia oil and sacred water down onto the ground; Lugalbanda shuddered (and) put (for) the LÍL-spirit (acacia oil and sacred water) down (onto the ground). The amalu,

ix: to Lugalbanda she spoke: "You - a wife from the mountain lands you have brought! The woman - it has lain together with you! [Female relative] (and) spouse - your son will be (as) an ornament! The good content of the word (it is)."

x: 5 men...

/////////////

The IM.RU of a-nun whispers around: "(In the ) outer courtyard (by) the gate, which lets unending (things) come in to me I want to take the ritual cultic ordinances!" The IM.RU of a-nun spoke: [....]"

Lots of grammatical commentary which I will spare you. How would you people interpret this? I am currently working at the concept of AbS 327 describing the sacred marriage between Lugalbanda and Lamma-Ninsumuna, with a blessing from Lugalbanda's (?) dead (?) personal female deity/mother concerning Bilgames by likening their son to me-te. The drink in the beginning is thought to contain drugs and/or high alcoholic content (cp. Selz 2004, Michalowski 1994, Pientka 2002) and has psychoactive effects; Lamma-Ninsumuna feels them first, and then the drugs culminate in an unio mystica as Lugalbanda and Lamma-Ninsumuna make hot, steamy Sumerian deity-human-love to each other. The IM.RU is thought to be a sort of essence carried by the gú-ku5r and a-nun - note the element IM. Another windy concept, possibly? Selz seems to think so. Anyways, the IM.RU is sacrificed so that the LÍL can come out of the ab-làl. What follows is the message of LB's personal female deity/mother to him, his new wife from the mountains, and the blessing pronounced at the ending.

Have to edit more, hope this is interesting enough. I has a sacred marriage

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jul 15, 2011 9:02:14 GMT -5

c Nadia: This updated translation is really an improvement - it looks brilliant!  Some really fascinating ideas touching on concepts which I am familiar with and others which I've long neglected.. The sacred marriage is something I've put off reading about for years now and on checking for the Lapankivi at the library the other day, the book was out 0_0 Nonetheless, I will proceed with some impressions, comments and open questions: About /i/ , the potion drug: I haven't heard anything like this yet, but it seems plausible in my mind! Although I'm lacking a Mesopotamian analogy of this situation, it brings to mind some modern aboriginal cultures I've learned about recently who smoke the leaves of a certain plant to get high - and believe it is the spirit of a supernatural being effecting them. /i/ the name d.lamma-nin-súmun: So in considering this name I have the disadvantage of being fairly unfamiliar with both Lama/Lamma/Lamassu/Lamassatu and Ninsun/Ninsuna/Ninsumun/Ninsumuna etc. etc. I'm sure your research on d.lamma has helped you out here - what strikes me as curious first of all is *why* is Ninsumun called d.lamma in this text?? For members who may be less familiar with Ninsun/Ninsumuna, here is Leick's entry for the goddess from "A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology." I should add she is commonly said to be the spouse of Lugalbanda: Her name means ‘Lady of the wild cows’. She had a sanctuary in Kullab, a district of Uruk and belonged to the herding-circle around Dumuzi; she is in fact his mother and therefore the mother-in-law of Inanna. Gilgameš was also said to be a son of Ninsun’s and in the epic she interprets his dreams. In the Neo-Sumerian period, several kings claimed to have been the ‘children’ of goddesses, such as Gudea of Lagash, as well as Urnammu and Shulgi of Ur. Leick's entry on Lamma: "Sumerian protective minor deity or demon, with a predominantly intercessary role. She is well known from the Lagash pantheon since the Early Dynastic period. Her cult was most popular during the Old Babylonian period; inscriptions tell us that one or more Lamas resided in the major temples. She may also be represented on cylinder seals, introducing the worshipper to the presence of a great god (Spycket). After this time Lamassu became a term for protective spirits generally.." Getting back to the question at hand then.. It seems relatively more common to encounter a faceless sort of Lamma, as in the Lamma of this king, or even the Lamma of this goddess or god, or just the "protective spirit" as is translated at ETCSL. But to the examples of d.lamma functioning as *an epithet* of a goddess, this seems more rare (at least, in my investigation at the moment!). Jacobsen's comment on line one of AbS 327 defines the d.lamma of d.lamma-nin-súmun just that - an epithet: "dlama(r), Akkadian lamassu or lamassatu, denotes a special kind of guardian angel. It is used throughout the text as an epithet of Ninsuna and it occurs with her name also in the za-mi hymns OIP 99 48:84, as pointed out by Biggs.4 The epithet is not unique to Ninsuna, but occurs with Irnina in the list of gods Weidner, AfK 2 (1924/25) 73:27: dlamma-Ir-ni-na = dIshtar. " And so Inanna/Ishtar is another goddess described in such a way - hardly the type of goddess I'd want on my shoulder (but I suppose she is relevant to the sacred marriage in Uruk..) I've read through an article by Ake Sjoberg's article "A Hymn to dLama-sa 6.ga" (JCS 26,3 1974) which treats an Old Babylonian hymn to dLama-sa 6.ga - here, a goddess in her own right local to Lagash. Sjoberg mentions that Ninsuna is called dLama-sa 6.ga in YOS 1 29, but as far as he can see, that's no reason to say she is the same as this dLama-sa 6.ga of Lagash. The text which Sjoberg treats concerns the Lama of the goddess Baba - that is, how the Lama of this goddess is great and how that Lama helps Baba. Therefore, in this case the lama is a separate entity, I suppose. The second half of CBS 10986 seems to mention beer and a garden although in different context - more interesting may be that the Lamma seems credited with giving Baba a husband and child - line 11 refers to the lama and line 12 "she" is refering to Baba I think: "11. Your name (is) like a... -cake, oil and cream, which fills the mouth, 12. When she brings in something from the street, when she'brews beer, it is of best quality, 13. She says that they should provide her with the best products from her garden, 14. Daily she is looking around in the house Girsu, 15. Daily (Baba??) walks brightly in front of you, 16. L a m a - spirit, . . you have given to 'this woman' a husband (who is) like a father, 17. You have given her a husband (who is) like a father, you have given her a son in place of a field that produces food." In any case, as Jacobsen mentions, the za3-mi3 hymn contains what may be the only other mention of d.lamma-nin-súmun (?). I had a copy of Biggs on hand and will type the text below. There is no translation, but the proximity of the deities invoked is significant I think: 78. gi en ki ki-sikil 79. dMes-sanga-unug za 3-mi 380. an gudu 4 dumu-nun 81. kisal en an-da mu 282. dMen za 3-mi 383. gi en ki zalag 2 ku 384. lamma dNin-sun 2 za 3-mi 385. ba 4 amar-ku 3 ub nun 86. dLugal-ban 3-da za 3-mi 387. IM ti she gu 88. dIM za 3-mi 389. LAK 4 nun Eresh 2 (NISABA) ki90. NISABA nun ta tuku te lul 91. dNisaba za 3-mi 3 Biggs makes the comment here: "Deities known from myths to be in a close relationship are often grouped together in the hymn collection." So obviously, Lugalbanda and Ninsumun are going to be grouped together; what may be interesting, in light of your interpretation of IM.RU as a possibly windy substance, is the precense of dIM following Lugalbanda in this hymn. I wonder if this could be referencing AbS 327 as well? /iv/ "grasping the IM.RU": IM.RU seems to be a definitively rare thing in Sumerian literature. For lack of my own massive philological note archive (seeing as I haven't learned Sumerian yet etc.) I tend to refer to Yoshikawa's database; yet even he records just one example of IM.RU , and it is AbS 327: htq.minpaku.ac.jp/databases/sumer/images/PDF/065/065-0035.pdf dIM seems most often to be one writing for the name of the storm god Ishkur/Adad. This is basically what I understand Schwemer to be saying in his ridiculously massive book Wettergottgestalten: "Die Schreibung des Sturm- un Windgottes IShkur mit dem Zeichen ZATU 396 = LAK 377 ("IM- + A") , die die Fara-Texte geben, mutet angesichts der Schreibung des Wortes "Wind" mit dem Zeichen IM- (ZATU 264 + LAK 376) ungewöhnlich an und widerspricht der Erwartung, der Name des Sturmgottes und das Wort für "Wind" würden mit demselben Keilschriftzeichen wiedergegeben. " Schwemer has recognized an Early Dynastic god dME.RU, who is known from the Abu Salabikh godlist; this god may be related to Mēr, a god identified with Adad or at least part of his circle. Schwemer seems uncertain (pg.202): "Wenden wir uns den Belegen im einzelnen zu: Schon Fara-zeitlich begegnet in der Gotterliste aus Tall Abu Salabikh eine dME-RU (lies dme-ru?) geschriebene Gottheit, die sich wohl auch als theophores Element in Semitishcen Personennamens der Fara-zeitlichen Texte nachweisen läßt..... ....Ebenso unsicher muß blieben, ob wir in den zitierten Farazeitlichen und vorsargonischen Belegen überhaupt den späteren Mer erkennen dürfen." So that's all I have on IM.RU - there may be a god from Abu Salabikh whose name sounds similar and who also may have something to do with wind. Admittedly, that means absolutely nothing because you could say that wind and wand are related because the words sound similar and both may move through the air 0_0 Adad/Ishkur may be ruled out of the equation on philological grounds, I suppose, depending on whether or not the IM sign is invoking the deity or not? I've no idea. I would say that that his conceptual relevance may not be as far off as some people place it; Schwemer is, by page number, is the reigning god of weather god knowledge, and yet I don't like his explanation of why it is that Adad is Shamash's assistent, as it were, in divinatory rites. According to my bad English translation, Schwemer says (pg.225): 'The [fundimental reason] for the close linkage of Adad with divination, and in particular their most standard method, the entrails, should be sought in that the specific utterances of the storm of God, especially lightning, thunder, and rain, since ancient times these were interpreted as being ominous phenomena. Even from Old Babylonian Mari, we have real records of meteorological phenomena that show attention to what is happening in the sky...' I prefer Piotr Steinkeller's interpretation, which, as I've mentioned elsewhere, recognizes that divinatory rites took place at night when the sun was in the netherworld; His assertion is that future knowledge traversed from below to above, and the reason why Adad was Shamash's assistant in this was due to his role as "cosmic wind", which assisted in the transfer of the message - perhaps much as windy spirits and dreams traversed to and from the netherworld, in conjunction with the sun god or his offspring. The relevant article is "Of Stars and Men:the Conceptual and Mythological Setup of Babylonian Extispicy" in Biblical and Oriental Studies in Memory of William L. Moran: Biblica et Orientalia 48, 2005. Editrice Pontificio Istituto Biblico, Roma. Additionally about IM as human spirit, there are the Old Babylonian funerary texts which I am aware of mainly through the work of D. Katz - indeed Katz' comments have surfaced now again on enenuru in relation to the text she calls "Lulil and his sister" - apparently, this text relates mainly to the dead god Ashgi, and his request to his 'sister' to send his wind-soul along - So why is this deceased unfortunate referred to by lu2-lil2? No one knows for certain (I don't think) but Katz now speculates that the Old Babylonian scribe used this term, lil2, to stress the ethereal quality of the word IM , which in the time he was writing, related predominantly (or even more so than before) to atmospheric phenomenona i.e. wind storms and rain. (Katz , "The Naked Soul: Deliberations on a Popular Theme." So the topic of d.lamma-nin-súmun and IM.RU are very fascinating - but certainly there are other interesting points on this new translation. Will have to pause for now. Nice work  P.S. Steinkeller had also a novel interpretation of Anunnaki which I wonder may inform a-nun.. I'll have to get the Moran tribute out from the library again. |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jul 17, 2011 2:43:39 GMT -5

A few other things - The complete CDLI entry for this text is rather useful: [url-http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/cdli/viewCdliItem.do?arkId=21198/zz001r4s2r]http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/cdli/viewCdliItem.do?arkId=21198/zz001r4s2r[/url] I've noticed that Claus Wilcke wrote about AbS 327 in the DUMU-E2-DUB-BA-A festschrift to Ake Sjoberg - his contribution entitled "Genealogical and Geological Thought in the Sumerian King List" pays quite a bit of attention to the lil2 as father of Gilgamesh thing, including a page and a half of discussion on AbS 327. I would not describe the interpretation and up to date at this point.. he says about IM.RU: "They [Lugalbanda and Ninsuna] create something (written IM.RU, (perhaps a pun as im.ru.a means "family"), which is not small -2 cubits are mentioned- and in which Ninsuna hides.." My suspicion is that some of that might now be overturned. In any case, Wilcke also gives a partial translation of AbS 327 in the RlA entry for Lugalbanda. I wonder if Jacobsen's discussion of IM.RU may still be partially applicable? In his comment to line 20 he clearly prefers a the value NI2 over IM - which may not be sustainable. But his comments for the sign RU seem interesting - could one interpret something like "to be beset with wind" ? But I suppose you can't very well grasp your 'to be beset with wind' (?) Jacobsen said about the RU sign: "As to the reading of the name, since the sign RU seems to have also a value ri., as suggested by the correspondence of im-ru with later im-ri-a (Image of Tammuz p. 383 n. 63), and since ri has the meaning rama, "to be beset with," a reading Ni-ri?(RU..." At the very least, note 63 of the book mentioned above may be important for interpreting IM.RU (if Jacobsen was correct). I am particularly interested in the line on column ix which you've translated "your son will be (as) an ornament!" - I have seen the cuneiform behind "54 me:/te dumu\-zu" and also the ePSD entry for mete - "wr. me-te; te "appropriate thing, ornament". I can't say that it means anything, but I've noticed a few lines in the Abu Salabikh godlist which seem, at least on first look, interesting for this situation. Alberti's 1985 "A Reconstruction of the Abu Salabikh God List" in Sel 2, givest the following entry at line 122-124: 122: d [ ] 123: dLuga[l]-ban3-da 124: den-mete What's interesting here is that Pietro Mander in his 1986 "Il Pantheon di Abu Salabikh.." seems to have used more sources than Alberti when he reconstructs the list - thus with his source he reconstructs Ninsuna: 122: dNinsuna 123: dLugalbanda 124: den-me:te Now to say that this has any bearing on Lugalbanda and Ninsuna is probably about as dangerous as saying that the sequence Ninsuna-Lugalbanda- dIM from the za3-mi3 hymns has any relevance - actually this may be even more dangerous, as I can't read Italian and don't have a great sense of the ordering logic (or lack there of) of the Abu Salabikh god list. I do suspect that it is a theological rather than lexical structure - that is, like the Fara god list the order has something to do with the authority or rank of the gods rather than some lexical principal as later god lists are ordered. Of course there is the problem of who is this den-mete - I suppose it could just be the deified Enmetana of Lagash for example, which would be a most boring result and it would mean this sequence is totally irrelevant. Bendt Alster wrote about the signs ME.TE in an article "En.mete.na: "His Own Lord" - in JCS 26, 3 (1974), pg 178. It is a discussion of the meaning of the name of Enmetena, primarily the question is, what does ME.TE mean? First of all, it mentioned that in Abu Salabikh texts, it may be written ME.TE or backwards TE.ME , as AbS 327 has it. Some scholars have interpreted that the name should be understood according to the epithet en-me-te un uki-ga, I think is what Alster says: 1) (thus e n m e . t e u n uki - g a "lord, adorn- ment of Uruk," and m e . t e g a - i, lit. "let me praise you fittingly" = m e . t 6 s g a - i - i ) Instead, Aster suggests it should be understood as an old phonetic writing of n i2 . t e - (a) - n a (- k) : 2) m e . t e - n a as an old phonetic writing for n i2 . t e - (a) - n a (- k), lit. "his own" (thus e n . m e . t e . n a) "his own lord," and l u g a l . m e . t e . n a "his own king/lord"). Or, in other words, he suggests a meaning of "his own" over "adornment". Interestingly, Alster states this phonetic substitution (me for ni2) is already attested in the Abu Salabikh version of the Instructions of Shuruppak. So Alster thinks en.me.te.na translates to "his own lord" as in nobody above him - he explains the significance behind such a name by stating: "And this idea is significant, for it is the point of two major literary compositions, the Lugalbanda Epics. Again and again they stress that Lugalbanda, he alone, could do what all others could not have done, or, as nicely stated by M. Civil, "n i r . g a l 'pride, self-confidence,' is one of the essential attributes of a hero." So I suppose the real question would be, does this reading of the signs make any sense in the text in question? There appears to be no EN sign, and so it couldn't be read "your son will be his own lord" I suppose. Perhaps it might be read "your son will be his own" however? This may be like saying the same thing, and seems to be in line with Lugalbanda epic narrative. Unfortunately I am completely untrained in Sumerian grammar - and have no ideas at the moment on how to test or weigh the notion that perhaps the den-mete on the Abu Salabikh god lists relates to in some way to Lugalbanda , Ninsuna and their offspring. I suppose proximity alone won't do hm  |

|

|

|

Post by enkur on Jul 19, 2011 5:33:24 GMT -5

This story confirms my persuasion of Lugalbanda as having attained to the self-initiation so necessary according to the universal criterion of becoming a magician. Lugalbanda's epos is a magician's epos for me. Could be of real use for eneneru if I was an ANE student and knew Sumerian, but anyway, what constitutes one as a sorcerer/magician is one's relation with one's personal guardian spirit or genius. Or, said in simple words, one becomes a magician when one comes to know one's true self. Though the Western occult traditions are inauthentic it doesn't make the experience of certain magicians less authentic. The greatest attainment in magic is reaching the point of contact with the personal genius. This attainment is called the Great Work (an alchemic term) and Crowley has defined it as "the Attainment of the Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel". The Golden Dawn tradition in this respect was based on a grimoire from the 15th century written by a Jewish magician (Abraham von Worms) - "The Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage" In brief, the practice of this sacred magic consists in retirement in total solitude for 100 days spent in special purification rituals and prayings to "God" for sending a guardian angel to the supplicant. If everything is done correctly the Angel appears to the mage and gives him control over "the 4 princes of evil" (or the 4 elements) and thus he becomes a magician. Another ritual used by the Hermetic order of the Golden Dawn for contacting the personal genius was the "Preliminary Invocation to Goetia" taken from the 17 th century grimoire "The Lesser Key of Solomon" - a magical system to call the 72 fallen angels and compelling them in the name of "God" to do the magician's will. One may recognize some pagan gods and goddesses from Egypt, Mesopotamia and otherwhere under these demonic disguises. At the time I had no nerves to read and study these obscurantist and dogmatic grimoires but Crowley has given much elucidation on this central topic of his system and given different and reformed versions of the older ritual practices. There are even better elucidations on the matter given by certain postCrowlean neo-pagan and other traditions. The essential thing to be known is that it's really a great ordeal for one's psyche and demads a constant will and determination. Some have ended in madness. The isolation/retirement/solitude for a certain period (preferably in the wilderness/ kur) is necessary - there are no substitutes for this practice. The stories about Lugalbanda confirm that rule. There is a lot of parallels in the so called primitive cultures survived nowadays. When one investigates the remnants of the pagan traditions one will also find traces of this magical quest of contacting the personal genius. It always appears to be of the opposite gender to the magician/hero and the relationship therewith is once and forever. A sacred marriage. Jung has also investigated these tradiotions prior to arrive at his concept of Anima/Animus. In brief, according to Jung, one attains to individuation (separating/unconditioning one's consciousness from the collective unconscious) when one has integrated one's personal subconscious Anima/Animus - usually of the opposite gender to oneself. According to Crowley the personal god is not to be confused with the Holy Guardian Angel. Becoming one with one's personal god via worship is regarded as a preliminary to the Great Work, which is attaining to the "Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel". This attainment makes one a divine incarnation on the earth because after it one already does one's true will which acts in accordance with the cosmic laws and nobody could stand on one's way. "Every man and woman is a star" as Crowley was told by his genius though the most of humanity are obscure stars who have no will to realize their potential: "The slaves shall serve" as Crowley was told by his genius. Maybe this is the true attainment which gives one the right to put the eight-rayed dingir star before one's name. Instead of "true" self which already became a dogma in the Crowlean circles, I prefer to say total self. Sometimes one's true self (or some significant component of the total self) could be of nature which is at odds with one's character and that makes the work even harder, so us4-he2-gal2  please, take this into account when speaking so about Inanna  (As far as I know Samuel Kramer claimed that Inanna was his guide after he broke with his Judaic religion. ) |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Dec 22, 2014 8:22:19 GMT -5

Sorry to those members who have noticed my above post remains incomplete. Taking some time to learn certain aspects of the grammar in this text and than to attempt an interpretation. Have updated with column 1 above, more to follow.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jan 5, 2015 12:59:46 GMT -5

On July 12 2011, a treatment of Lugalbanda and Ninsumuna was posted above by nininimzue (N. Linder). This text has long fascinated me because of its inclusion of a lil2 spirit and, further, the enigmatic IM-RU - the importance of this thing/spirit/essence to the narrative is clear when you read over the post above and the translation and comments provided, however the exact interpretation of IM-RU is not clear to the contributor nor has it been clear to scholarship in general.

Well, IM seems to be reasonable easy to interpret. At least, we know this has a certain range of meaning and above mentioned contributor suggested: "another windy concept perhaps?" as in, another spirit like entity along with lil2. The relation between these concepts has been explored by D. Katz among others. Wind or spirit are possible. The sign RU can stand for a number of nouns and verbs, one possibility is that is may be used to write the verb šub: "to fall; to drop, lay (down); to thresh (grain). This has an equivalence with the Akk. nadû

Today I have noticed at random that im-ru is listed in MEE 4, a volume which treats bilingual (Sumerian/ Semitic) lexical texts from Ebla. Entry number 1338 gives:

im-ru = pu3-a-tum. In Black's concise dictionary of Akkadian, puātum is given an equivalence with later puādum which means simply "word" (=awatum).

This application of this semantic value may be reinforced in section IX which ends with "The good content of the word (it is)." The question is, how to conceptualize IM (wind/spirit) and RU (possibly 'cast down') with the nuance of "word" ? While I may shortly be able to ask some people at the Uni. about this, and update this post, I seem to recall that the Akkadian word nadû is often used in conjunction with the casting of a spell, literally to throw down - to throw down the words of the incantation, so to speak. It is the same in English, when you say "to cast (down) a spell."

More to come.

|

|

|

|

Post by enkur on Jan 6, 2015 10:08:40 GMT -5

For me the mystery is that im could mean both spirit and clay. So man was made both of clay and spirit. (The component of divine blood appears in the Akkadian myth of Atrahasis). IM.RU of a-nun which speaks... IM.RU of noble sperm?

|

|

dingo

dubsartur (junior scribe)

Posts: 21

|

Post by dingo on Jan 6, 2015 12:31:40 GMT -5

The Sumerian term IM.RU could also refer to 'family' or 'clan' - see the PSD under imria [CLAN] where it is also spelt IM.RU and IM.RU.A

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jan 12, 2015 12:01:28 GMT -5

Analyzing AbS 327 - Lugalbanda and Ninsuna Again Dingo: Yes, you have astutely pointed out what should of course been an obvious step: consulting the ePSD. I actually hadn't got to looking up IM.RU on ePSD but as you will see below, I also came to this information (that IM.RU be interpreted "clan/family") by a less direct route. So good point! As can be seen in the above posts, the text we are dealing with comes from Early Dynastic Abu Salabikh, AbS 327 (CDLI P010263), and is one of the most significant pieces of early literature. So during Sumerian class last week I brought up the question of IM.RU to Krebernik and asked what his opinion was on the MEE 4 lexical entry (the bilingual Sumerian/Semitic lexical list from Ebla which I referenced in the above post). MEE 4 gives the following equation: im-ru = pu3-a-tum

As I stated above, on referencing Black's Concise Dictionary of Akkadian, I found an entry which seems to indicate that pu3-a-tum can be understood to mean simply "word." Krebernik found some of this interesting, but had reservations about just using Black's Concise dictionary and indicated more research would be needed (which of course I expected) but also he informed me that it is more common to understand both im.ru and pu3-a-tum as "family." And on this point, he referred me to the work of one of his former/current students, Mohammad Hajouz, whose PhD work is a 900 page book exploring Semitic words known from Ebla. Very useful! Dr. Hajouz' entry for the Semitic root p-ʾ(-t) (=pu3-a-tum) cites the ePSD entry: "Das Sumerogramm IM.RU bedeutet „clan“, akk. kimtu [ePSD]." He believes that the /t/ here stands for the feminine marker and that the word may be related to the Arabic fiʾa "group" ("Die ebl. Entsprechung pu3-a-tum bezieht sich möglicherweise auf ar. fiʾa Pl. –āt „Gruppe, Klasse, Schar“ [Wehr 937].") It seems to me that there a small number of scholars behind reading pu3-a-tum as "word" as I had been intrigued by earlier this week, but mainly the lexicographers: so both CAD and Black's Concise Dictionary of Akkadian seem to refer back to and rely on an entry found in von Soden's aHw (German dictionary of Akkadian) which simply states: puād/t/ ṭum ? , aA. G. Prs. awatam (Wort) that is "word." But outside van Soden's now quite dated suggestion, scholarship in general seems to have moved strongly in the direction of understanding the word as "family/clan." For example, Visicato's 1995 work "The Beaucracy of Šuruppak" (which focused on ED economic and administrative texts) notes the following on the subject (p.17): v. I1 3: the term im-ru has been translated by Th. Jacobsen as "clan"; he

derives it from the same root as the term im-ri-a, akk. kimtu, "family" (MSL 5, 17,

117). A. Falkenstein has translated it as Gerarkungen, "district" (cf. D.O.Edzard,

Fara und Salabikh. Die "Wirtschastexte", ZA 66 [1977], p. 173, sub TSS 245). The

bilingual dictionaries of Ebla have im-ru = pu3-a-tu (cf. MEE IV, p.336, 1338')

perhaps derived from the akk. pāṭu, pattu "district" (suggestion by P.Steinkeller)."

In any case, Krebernik suggested that the context of the narrative must dictate the meaning of obscure terms like IM.RU therefore we would need to assembly some translations and interpretations of the text. In order to do that, I am collecting some sources for now. The relevant bibliography is listed at CDLI and I have included it below: digital2.library.ucla.edu/cdli/viewCdliItem.do?arkId=21198/zz001r4s2rBiggs 1966, 85; OIP 99, p. 91; Bing 1977; W.G. Lambert 1981, 87; Wilcke 1987-90, 130f.; Alster 1992, 63

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jan 31, 2015 19:49:43 GMT -5

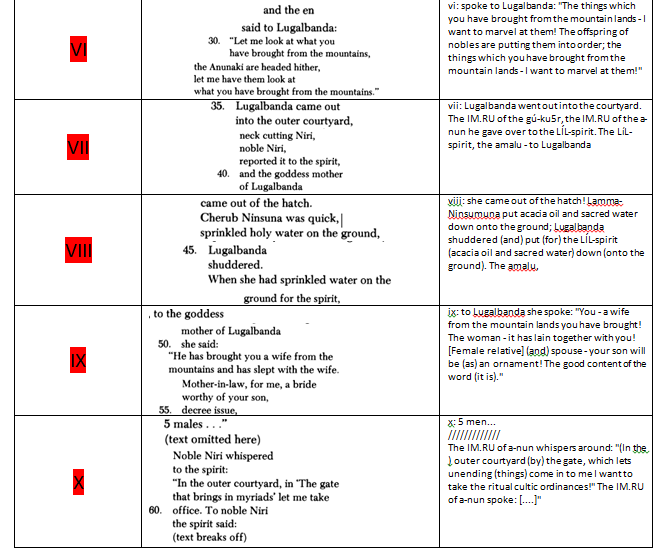

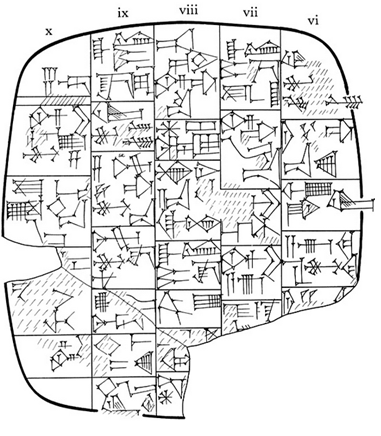

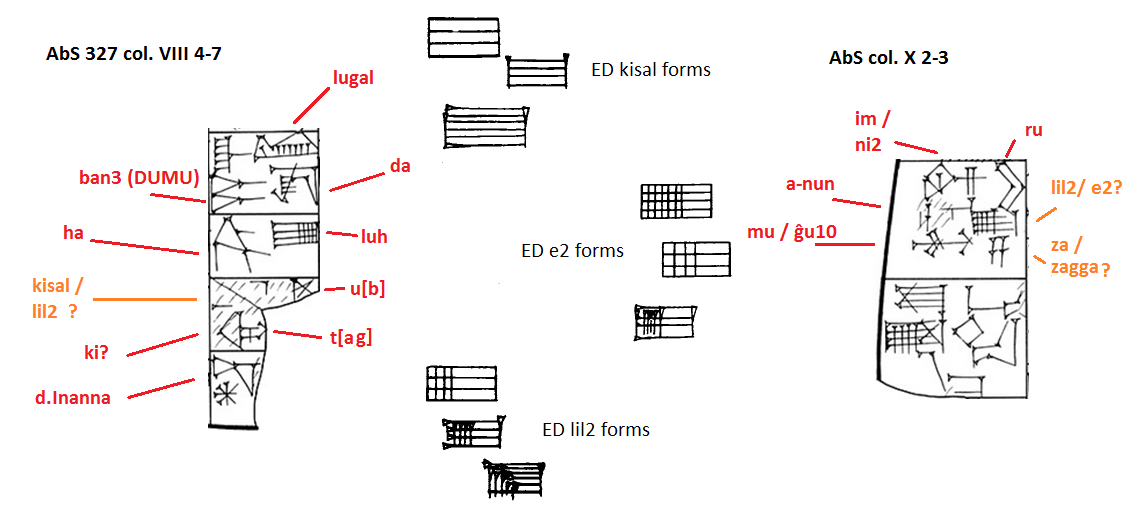

Continuing.... So, I have been able to compare 4 different translations of AbS 327 in the last week, with the aim of gaining a better understanding into the context of the text. As Jacobsen himself once stated, the difficulties involved in reading and translating an ED piece of literature like this are significant, and as a result there is considerable variance from one scholar to another, unfortunately. This creates confusion, so what we may attempt now is to lessen that confusion..or at least to explore it further. The 4 translation I have collected are a) Jacobsen 1989 "Lugalbanda and Ninsuna" JCS 41 no. 1 pp. 69-86; b) Bing 1977 Gilgamesh and Lugalbanda in the Fara Period JANES 9 pp. 1-4; c) Linder 2011 (unpublished, see this thread Jul 12, 2011); d) Wilcke 2011 (unpublished, I refer to a prepublish version of this scholar's latest work on Lugalbanda). Wilcke's initial PhD work centered on the epic of Lugalbanda, and since this time he has remained the expert of the subject (he wrote the RlA entry on Lugalbanda), hence I have been fortunate to be able to access his latest translation of the AbS 327. As enenuru has been focused on (among other things) the discussion of the Mesopotamian notion of spirit, the occurrence of lil2 in this text is of high interest. The reading of the relevant sign as lil2 is not universal among translators however. IM.RU is another item of high interest of course, as it's reading and interpretation remain elusive in this text. A third term over which the understanding of the text hinges is the term a-nun. I intend to examine the following problems in more detail below: i)lil2

ii) IM.RU

iii) a-nun

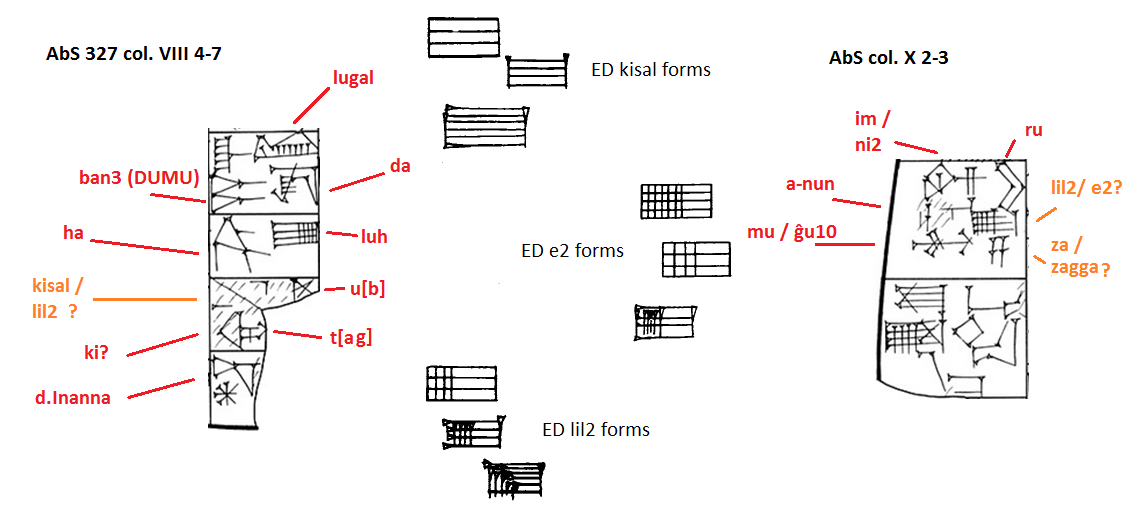

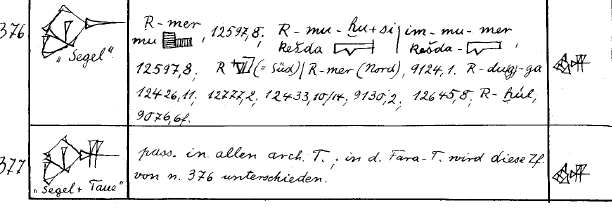

While I am not at liberty to put all of this material online (for example, the Wilcke) I have included two full translations in chart form below so that enenuru readers and visitors can get a sense of the basic narrative of the text, and some of the differences in translation: Please note that the column number (which I have marked in red above) corresponds to the relevant column on the observe and reverse of AbS 327, as can be noted in the below line drawings (taken from CDLI): Philological problems/ i) lil2 If there was agreement on the presence of a lil2 spirit in this text, I would be pleased. However, there isn't and while two translations maintain the reading lil2 in column VIII and X (Jacobsen as well as Linder), Wilcke's latest treatment of the text does not. Below is a chart comparing 4 treatments of column VIII wherein lil2 may or may not first appear. Bing's treatment was largely discounted by Jacobsen in comments he made in his 1989 article (pg. 72). I have translated Wilcke's translation from the German for the sake of convenience.  So, the real point of contention comes in line 6 col. VIII which Wilcke reads: Lugal-bàn-da, ḫa-luḫ, ⌈kisal⌉ [a?] ⌈ki ub⌉-ta[g] ; importantly, instead of reading lil2 after "Lugalbanda became frightened" (Lugal-bàn-da ha-luh), Wilcke reads instead kisal. I understand this to translate simply to "courtyard" as it occurs also later in the text, however the translation "courtyard" (oddly) is not reflected in the author's translation here. Nonetheless, the question now becomes: which of these readings is more convincing? The relevant cuneiform sign must be examined.  As can be seen in the above, line 6 or col. VIII is badly preserved. The relevant sign, occurring at the start of the line, is impossible to identify short of saying, well, it appears quite rectangular - both kisal or lil2 are possible readings. Therefore, to extrapolate further, we can look ahead to the next time that Jacobsen translates "(lil2) spirit" and this occurs in line 2 col. X (see above illustration, left side). Finally a visible sign which leads Jacobsen to read "lil2" and Wilcke to read "e2" : so is it "Noble Niri whispered to the spirit" or "My relatives, and the Anuna of your house" ? While there are several variables at play here, much hinges on the reading of the sign as e2 or lil2. Wilcke's reading e2 here against Jacobsen's lil2 is indeed very reminiscent of the debate surrounding the name of En-lil2: Against Jacobson and the traditional readings, Steinkeller argues that the name of En-lil2 was written with the e2 sign (En-E2) throughout the third millennium. This in turn was refuted by Wang and R. Englund - see, the name of Enlil thread. The point is, the similarity between these two signs has been confusing scholars for decades and here we have an excellent example of the same problem.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Mar 27, 2015 20:25:58 GMT -5

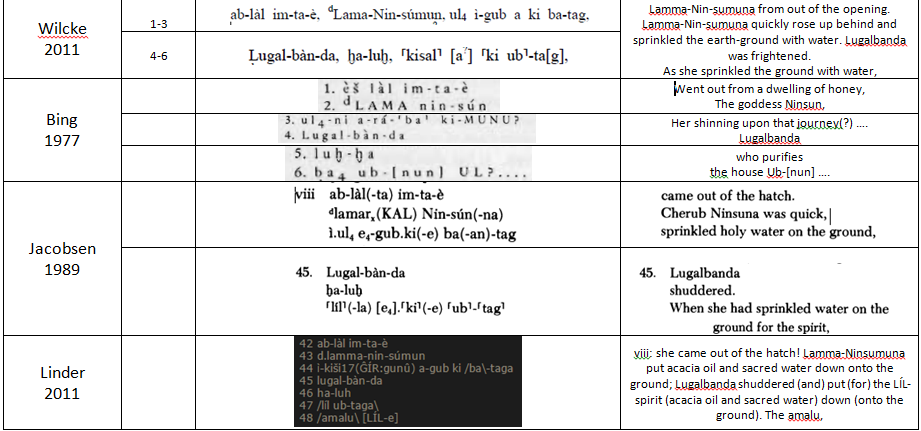

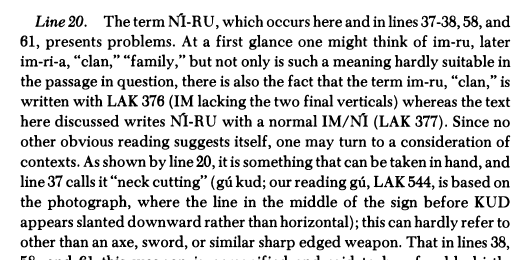

Continuing.... Philological problems/ ii) IM.RU When I asked Prof. Krebernik how to deal with this issue of IM-RU in Lugalbanda and Ninsuna, he told me that I would need to try and work it out by context. As pointed out above, this of course entailed tracking down some translations of the text. Now I am examining the problem of IM.RU with particular attention to the context in which it occurs. IM.RU or NI2.RI?/ Jacobsen writing some 26 years ago already gave high priority to the context in which the term appears, as is apparent in his commentary to line 20, ("Lugalbanda and Ninsuna" in JCS 41): When the author makes reference to the signs LAK376 and LAK377, these are entries in Diemal's classic Fara sign list, seen below: So before proceeding too far, the issue of whether to read IM(LAK376).RU or NI2(LAK377).RI must be dealt with. These signs are very close: NI2 is simply the IM sign with an additional 2 verticles on the end (the a sign). There seems to have some semantic overlap between these signs which has already been examined on the Studies in Sumerian Semantics thread. But the challenge here is more fundamental: which sign value was intended by the ancient scribe? While most scholars seem to read IM here, Jacobsen reads NI2. Clearly, when one examines the relevant sign (see col. iv and x on my post Jan 31 above) the sign does indeed appears to be LAK377, that is NI2, composed of IM + A. I was fortunate to have a chance to ask G. Selz his opinion when he came to Jena, and (very briefly) he seemed to favor the reading NI2 as well. This seems to be echoed in his paper Was Bleibt der Sogenannte "Totengeist" und das Leben Der Geschlecter (ii), footnote 17, wherein Selz suggests that the etymology of the known term im.ru 'clan' may have been ni2.ri.a with an approximate meaning of 'fathered by the selfsame person' ("eigentlich von einer Person gezeugt"). This translation of ni2.ri.a is not fully compatible with Jacobsen's use of NI2.RI in this text, however, as in the latter's view, the term entails a 'neck-cutting' weapon (not a 'neck-cutting' ancestor). Against this school of thought, Prof. Krebernik has pointed out that the scribal convention in Abu Salabikh at the time this text was written was to always write the NI2 sign, even when IM was intended! And looking at other parts of the same tablet, AbS 327, one notes that on col. vii, in the verb im-ma-ta-e3, that im is indeed written with the NI2 sign, and here it is read by Jacobsen and Wilcke alike as im (however, IM appears as IM (not IM+a) on col. iv). Still, Krebernik's observation seems supported by OIP 099, 33 (CDLI P010093), and OIP 099, 66 (P225942), to give a few examples. This is a strong argument against Jacobsen's reading NI2.RI. At the moment I am persuaded to see IM.RU as the intended value in this text, but the reading remains, all said and done, ambiguous. IM.RU in context/ One thing I like about Jacobsen's comment was the logic that whatever IM.RU is, it must be a physical noun that can be grasped by the hand. This is really the heart of the problem, and it comes from col. iv where IM.RU is followed by the compound verb šu im-ti - as recently explained here (Mar. 24 2015), šu ...ti is a verb formed by combining the šu (hand) + ti (to approach) which then means 'to receive' and conceivably to grasp as it has been translated by Jacobsen, Linder and Wilcke ("ergriff"). The traditional meaning of IM.RU is, of course, a group, particularly, a kin group, relatives. One can't grasp this in the hand really, or this would not seem to make sense in the context of this line. For Jacobsen, the solution is to infer that it is a weapon being grasped (based on his translation of surrounding words which he sees as spelling out "neck-cutting"); for Linder, it was most expedient to avoid the entire problem by not interpeting IM.RU i.e. Lugalbanda 'grasped the IM.RU' ; for Wilcke 2011, the solution seems to have been to supply a word that wasn't there. That is, his translation suggests that what was grasped was 'die Verwandten(-Liste)' that is, the ancestor (list). By supplying the word 'list', Wilcke overcomes the problem by proposing that the object is a cuneiform tablet (for what else could a list be written in those days?) and thus something that could be grasped. In the very next column, col. v, mention of a tablet "dub" does occur, and Wilcke translates "He rose, brought the clay tablet hither.Lugalbanda prostrated himself before him" (where Jacobsen had given the interpretation: "let me set out with you, for the 'tablet of deliveries'. Lugalbanda prostrated himself on the ground"). However, Wilcke's line of interpretatoin does seem to encounter a problem when on col. vii the word gud2 'neck' appears in relation with the IM.RU, leading Wilcke to translate: "Kaum hatte er der Verwandte(-Liste) den Hals gebrochen" (Just when he had broken the neck of the list of relatives). This does seem a little awkward, as cuneiform tablets don't really seem to have a "neck" that I am aware of. My interest in this problem was sparked a few months ago when I encountered an entry in the Eblaite Lexical lists IM.RU = pa3-a-tum (Jan 5, 2015, above): im-ru = pu3-a-tum. In Black's concise dictionary of Akkadian, puātum is given an equivalence with later puādum which means simply "word" (=awatum). In the end, it seems only the lexicographer's ever maintain such an understanding of im-ru/puātum (Black, CAD, from the original work of von Soden AHw) - following a closer look at the context and the words involved, nothing would support this value especially in our current text as words, obviously, cannot be grasped by the hand. As it stands, I am most persuaded by Wilcke 2011, while it is apparent that this attempt to is, of course, highly interpretative.

|

|

|

|

Post by Lu-uri-ning-tuku on May 2, 2017 5:15:38 GMT -5