|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 11, 2009 7:12:57 GMT -5

and another motive of a man holding two snakes source information is :Basin From Mesopotamia. Steatite. A man is strangling two snakes, flanked by reclining lions.  |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 11, 2009 7:39:36 GMT -5

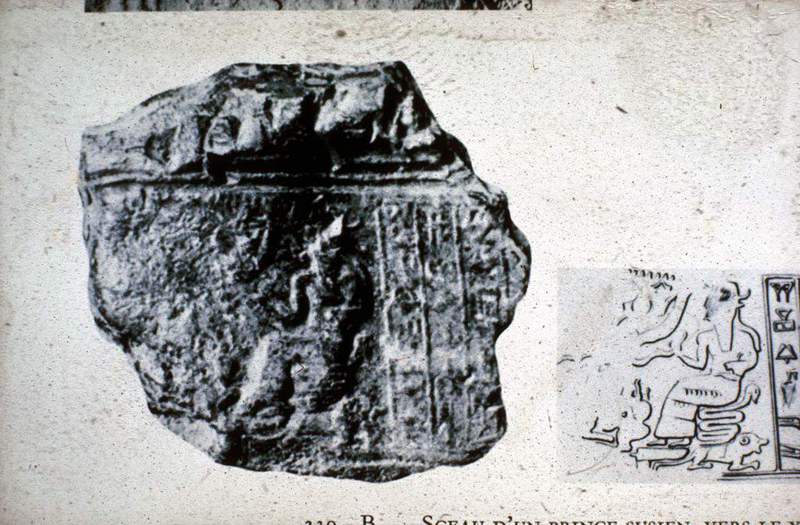

Imprint depicts a Susian prince/god holding a serpent on a serpent throne.  |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 11, 2009 8:15:18 GMT -5

Bust of a statue of a divinity, Iran. Elamite Period. Middle Kingdom. 13C BCE Limestone. if you turn the picture 90° clockwise you can see hands holding two snakes.  |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 11, 2009 8:19:51 GMT -5

Cult scene. Iran. Elamite Period. Old Kingdom. 17C BCE. Seal a snake displayed on the left  |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 11, 2009 12:45:25 GMT -5

Enthroned god Kurangum. Iran. Elamite Period. Middle Kingdom. 13C-11C BCE Stone Carving sitting on a snake throne  |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 11, 2009 13:04:56 GMT -5

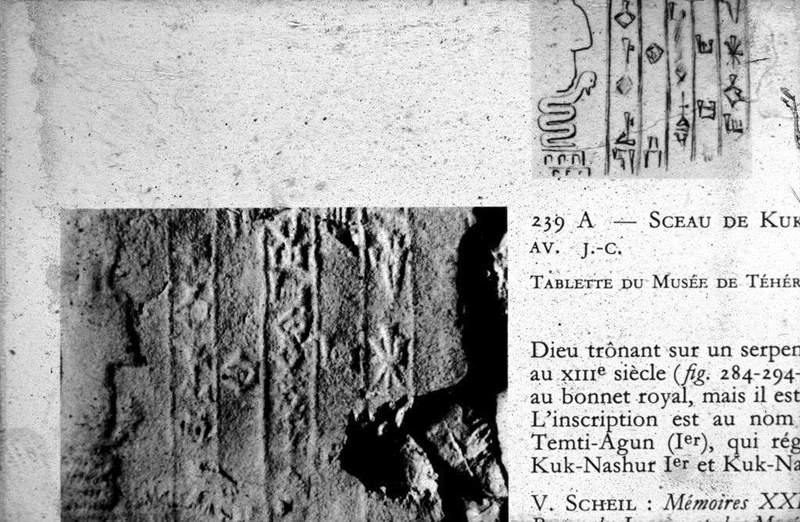

Cylinder seal imprint of Kur-Nashur I.(sitting on a snake-throne) Iran. Elamite Period. Old Kingdom. 17C BCE.  |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 12, 2009 14:47:37 GMT -5

thanks naomi

no, that arent dogs....that are lions post96 say

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 20, 2009 17:03:45 GMT -5

A seal imprint from Tepe Gawra displaying a snake.  |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 7:01:46 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 7:10:44 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 7:15:46 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 7:20:42 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Mar 4, 2009 7:44:16 GMT -5

Eureka!!

the MOTHER LOAD!!!!

0_0

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 8:22:40 GMT -5

I just found a more colorful version of cylinder seal number 709 from above´s post  CYLINDER SEAL: the legend of this seal identifies its owner as Bilalama, son of Eshnunna's ruler Kirikiri; the seal design depicts a presentation scene: Eshnunna's city god Tishpak (identifiable by two snake dragons emerging from his shoulders) is seated on the right side; he is faced by a bald-headed worshipper, who is followed by a suppliant (Lamma) goddess; between god and worshipper a divine attendant figure material: lapis lazuli, with gold cap provenience: Palace of the Rulers at Tell Asmar (stolen from excavation but recovered from an antiquities dealer in Baghdad later on) date: early Isin/Larsa (ca. 2,000 B.C.)>nr ?Find Number: As. 30:1000 Museum: Oriental Institute Museum Museum Number: A7468 |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 10:16:29 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 4, 2009 17:11:29 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 15, 2009 14:19:56 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Mar 15, 2009 14:50:13 GMT -5

Sheshki : I am here pasting a comment that Madness reported earlier, taken from Wiggermanns Transtigirdian snake gods. Here Wiggermann refers to the scene on the obverse. Nice work  " A more developed form appears on an Akkadian alabaster relief group from a private house in Ešnunna, in fig. 2b. The dragon is now scaled and has the head of a snake, but is missing the horns and the hind-legs are not yet those of a bird of prey. The god standing on the dragon, either Ninazu or Tišpak, is also scaled, and is not yet completely anthropomorphic. Since the piece was found in a private house, it probably played a part in the cult of dead ancestors, the typical house cult [Conceivably a domestic version of the important role played by Ninazu in rituals for the royal dead]."" |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 26, 2009 12:45:15 GMT -5

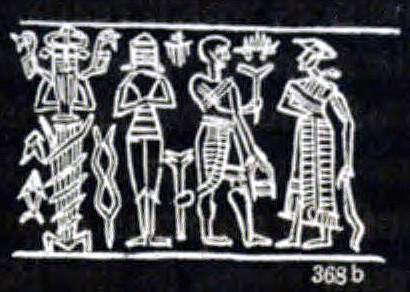

The Seal Cylinders of Western Asia page 127/28 www.us.archive.org/GnuBook/?id=sealcylindersofw00warduoft#167from the chapter: " The serpent Gods" ... This design already shown is from its impression on a tablet; but a single cylinder is known, from the great collection of the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which gives us a representation of Ningishzida, but here not as an intermediary (fig.368b).  The cylinder, which appears to be somewhat later then Gudea, is of hematite. The god stands in the form of an image resting on feet like those of a tripod. The garment is contracted below, like the bronze images. The face is in front view, and there are two protuberant ears. A serpent rises from each shoulder. The hands are folded on the breast. Perhaps the garment might not be regarded as flounced, but as having something wound about it to draw it to the body. On one side of Ningishzida stands the nearly nude Zirbanit, and on the other a deity, perhaps female, with a necklace (or beard?), holding a scimitar. A worshiper approaches carrying in one hand a pail and with the other lifting a crutch-like object, above which is a tortoise. The other emblems are the thunderbolt of Adad, the vase and "libra", a fly and a fish. This cylinder is of interest as showing that the whorship of Ningishzida continued probably a thousand years after Gudea. |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 26, 2009 14:21:53 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Mar 26, 2009 15:07:15 GMT -5

Xuch posted the drawing of this one a few month earlier. found here: ecai.org/iraq/IraqCulturalArtifacts.aspGoddess from the Other World2000-1600 B.C. Isin-Larsa-Old Babylonian period. Hematite. Cylinder seal. Mesopotamia An enormous winged bird-footed goddess stands frontally with hands clasped. A double register scene appears alongside her. In the upper register a nude goddess and a bearded deity receive homage from human worshippers. A row of composite beings appear in the lower register. A fly, a hedgehog(?), and a human head appear above these creatures in the field. This goddess with bird features has been identified with Lilith. She may represent the chthonic aspect of Inanna/Ishtar derived from her association with the demonic and frequently bird-like creatures and gods that inhabit the underworld. Here, the goddess¹s horned head appears alongside deities and their human worshippers while her bird-feet appear beside demonic creatures. The hierarchical arrangement of this scene may signify her dual nature, partially of "heaven and earth" and partially of the underworld. |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Aug 3, 2009 16:18:28 GMT -5

In this post I have copied some reading I am doing for Abrahadabra on the subject of the ushum and bashmu snakes:

Hey Abrahadabra:

Well, it seems I'm always presenting complicated and touchy explanations here, I suppose it may give the impression that everything about Sumer is laborious.. I would agree many things are, but I guess as I've remarked before, your particular focuses here may exaggerate this impression as the netherworld gods and the snake gods are elusive (and so a stressful subject to discuss.)

So I'm putting something together to delineate between the Ušumgal and the Mus hussu. The iconography and mythology of both of these creatures is more often vague and more often in some process of change than in stable and concise condition; the nomenclature associated with both, as we witness it in this or that article, is in a steady state of flux between Sumerian, Akkadian and differing modern conventions for rendering ancient text; the associations of both creatures revolve around the same deities, but for different reasons which may at points have more to do with the shifting social-political climate of Mesopotamia than with appreciable religious sentiment. For reasons such as these it can be difficult to explain concrete distinctions between the two. To begin with, I am intending to quote a large section from the enenuru Ningishzida thread, (reply #47) - in that post I had referred to a discussion given by Anthony Green who understands the snakes at Ningishzida's back as the Bašmu snakes, possibly to be identified with today's species cerastes cerastes. I will then update this material with some new insights from F.A.M. Wiggermann from his book "Mesopotamian Protective Spirits" (MPS) (the book I should mention, is extremely technical and focused on a very narrow range of ritual texts). Hopefully below my modified look at Bašmu should also add explanations for Ušum and Ušumgal which I hadn't worked in before, and the dissections with Mus Hussu will stand out.

On the Identity of the Ušumgal/

From Enenuru:

"In regards to the snakes at Ningishzida's back, we can turn again to A. Greens article found in CANE vol. 3, specifically pg. 1844. Near the bottom Green states:

"Another underworld god was Ningishzida. As he was the personal deity of Gudea, ruler of Lagash, he is depicted in the art of that time- for example, on Gudea's own cylinder seal, where the god introduces the ruler to the water-god Enki. Ningishzida is represented with horned Bašmu snakes (the horned viper Cerastes cerastes) rising from his shoulders (see fig.5 no. 4)."

When we refer to "fig.5 no.4" , which is on pg. 1848, we see that no.4 is a little drawing of a horned snake. The accompanying information tells us, that this image is attested from the Akkadian (?) period, down to the Kassite period. It's

proposed identity, its names in semitic language, are 1. bašmu and 2. ušumgallu and the proposed translation for both is "poisonous snake."

_____________

Wiggermann adds important information on the topic of the identity and nomenclature of the Horned viper - in his more concise discussion from MPS, he explains that the Sumerians had two terms, ušum and muš-ša3-tur3 - the first a horned snake with front feet, the second a horned snake without front feet.

For these two terms, the Akkadians had only one term: bašmu. (We see that above, Green states bašmu and ušumgal are the semitic terms, proving that Assyriologists contradict each other all the time - more on the ušumgul later.) So what this means is that, yes, ušum is another word for the snakes at Ningishzida's shoulder, footed sort or no.

The Character of the Ušum, Bašhmu/

The earliest texts from which we may get a sense of this creature are the Early Dynastic incantations (2600), these are a favorite reference source of mine despite that they are currently only published in German and often are somewhat inexplicable in any case.

In these earliest examples of Mesopotamian incantation text, the principal causes of problem illnesses are the Udug demon, Enki, and snakes. Snakes are an understandably object of fear for the ancients, and the mysterious and deadly power of venom was a subject of fear and awe - the image of the fierce venom spitting serpent is one often applied often the gods (who were much feared and at the same time revered). These earliest texts indicate a period in which period where Enki was especially associated with illness bringing snakes, a fact which comes to some surprise to readers of later Mesopotamian literature - later literature stresses this deities position as a lord of benevolent incantations .. however, the ancient world offers numerous examples of deities specially associated with both the power to cause and to cure illness i.e Apollo.. the logic may have run that the one with lordship over the weapon is the same who may heal, even if that is to do so little as to refrain from unleashing it. This ambiguity of nature, neither definitively good nor evil, is characteristic of Mesopotamian religion at large, and we see many "daimons", entities who may act as agents of illness yet at the same time be employed protectively in

other contexts. In any case, G. Cunningham writes a brief note about Enki's association with snakes in the early incantation texts, to include the Ušum:

"Text 26 refers to 'the snake of Enki' (muš d.en-ki) while text 27 refers to 'the place of the black snake in the middle of the abzu' (ki muš-gi6 SU.AB sha) as well as mentioning the black dog, a horned snake, a serpent (the ušum) and Enki himself."

As Wiggermann notes the ušum/bašhmu "is perhaps nothing more than "Venomous Snake"; a natural enemy of man mythologized." The snake itself is therefore harmful, but it may nevertheless represent or be associated with deities who, while having the ability to inflict suffering, are essentially worshiped as protective deities (as in the case of Enki).

The Ušumgal/

Now that we have defined the ušum/bašhmu, what then is the ušumgal? As I mentioned above, the word ušumgal is a combination of ušum (= snake or noble snake) and gal (great).

Ušumgal is often translation "dragon". Wiggermann relates that the Sumerian ušumgal is written in Akkadian either by "bašmu" or by "ušumgallu" .. "it is a derivative from "ušum" and literally means "Prime Venomous Snake"... the foremost quality of an ušumgal (and probably of an ušum) is being a determined killer,killing probably with its venom, and frightening even the gods.. it is this quality that makes ušum(gal) a suitable epithet for certain gods and kings."

The differences between ušumgal and the more general ušum seem very indistinct - while the latter is perhaps more representative of the mundane venomous snake, the former may be better understood as a more mythologized version, a chaos monster (this distinction is hard to assert for reasons that

will become apparent below).

Chaos and Chaos Monsters/

Beginning in the Ur III period, incantations began to be directed not only against daimons and snakes (as in earlier periods) but also against chaos monsters. The beings were often a composite of different animal forms, and unlike daimons (but like snakes), they only caused harm - they embody disorder as well as cause it. " Therefore the muš-ḫuš associated with Ninazu is a chaos-monster, which in some periods is treated like a daimon, is a bringer of sickness and disorder, and is targeted in incantations. (Ninazu here is similar to Enki, sometimes referred to as "king of Snakes" in some incantations, he is capable of releasing and restraining the serpents, again showing a dual nature).

Chaos Monsters are generally, but not always, composite creatures - they get their name as they are creatures that appear on lists of defeated opponents of the gods Ninurta or Marduk. These are deities who battled chaos and enemies of the divine order during the forming of the cosmos, enemies such as the seven-headed dog (ur-sag-imin), six-headed wild ram (šeg-sag-aš) or the ušumgal. Once defeated, they generally became sub-servant to divine will, but divine will was also interpreted as instrumental in bringing about human suffering (for in Mesopotamia, nothing could be acknowledged to escape the control of the triumphing gods of order, contradictory as this often ends up being.)

For persons attempting to distinguish between the ušumgul and the ušum, it is confusing to note that both forms of the horned snake appear in the lists of defeated chaos enemies, but G. Cunningham explains this in part:

"Snakes can also be regarded as similar to chaos-monsters, given that in Mesopotamian terms they are classified with the same conceptual continuum as chaos-monsters of the serpent-type such as the ušumgal."

Conclusions from this post: While it's possible to call either the ušumgal or the ušum a "dragon", and this is not necessarily incorrect, the word is more of a convenient English term which may carry with it connotations which are inapplicable. The ušum in form is simply a horned serpent which may or may not possess forelegs (varying), and it's mythologized big brother, the ušumgal, is the same if not larger. Now that I've clearly recognized the equivalence of the Sumerian ušum and Akkadian bašmu, the snakes which occupy Ningishzida's shoulders and which are thought to possibly be his pre-anthropomorphic form, this suggests a new explanation to me about how he got his later role in exorcism.. When we recognize that in earliest incantations Enki, the principal lord of magic, was capable sending and restraining snakes, and again Ninazu's similar capacity (he is called "king of snakes" while at the same time his importance as a healing god is apparent), Ningishzida's association with the ušum/bašmu and its subservience to him may in the same way recommend this deity to exorcists always anxious for effective defenses against the fearsome venomous snakes. This suggestion would be an alternative to the possibility that his legitimation as an exorcist stems from his late appointment as Throne bearer in the Netherworld.

Wiggermann also hints of a snake that may have been even earlier associated with Ningishzida, which I still am attempting to read up on however.

Still to come... Further perspective on the mus hussu, the snake Nirah, and the ušum.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Aug 10, 2009 16:03:17 GMT -5

Bašmu/Ušum, Muš huššu, Nirah Hey Abrahadabra: I'm writing a follow up to the above post regarding snakes and snake monsters in Mesopotamia. In this post I hope I will be able to add some additional details on the Muš huššu and on Niraḫ, and together with whats already been noted about the Bašmu/Ušum and Ušumgal snakes, this would be a reasonable accounting of Ophidian lore in Mesopotamia. The Transtigiridian influx/ I'm fairly certain that I have detailed the Muš Huššu and the Transtigiridian influx before, but I will give a version of that information here again for the sake of being through and for delineating between this creature and the ušum. In discussing Ophidian traits in Mesopotamia, which the Muš huššu and the gods this creature is associated with posses, it is important to recognize the influence of the lands lying to the east of the Mesopotamian plateau, across the Tigris (hence the term "transtigiridian"). Elamite culture, which occupied the Iranian highlands and held sway over cities along the current Iran/Iraq border, is known to have had special religious emphasis on snake deities, and this trickled into Mesopotamia proper. Recognizing this influence allows one to better understand how seemingly disparate deities from the North Eastern Mesopotamian city of Der seem to share things in common with snake gods from the Southern Mesopotamian plains such as Ningishzida - Der was on the border to Iran and thus acted as a transfer point.. as Wiggermann comments: "It can of course not be denied that Ninazu and Ningišzida are Sumerian gods, but the evidence suggests that their Ophidian traits were developed under theinfluence of transtigridian religious ideas. In fact, as has been repeatedly shown, a religious interest in snakes in these regions goes back deep into prehistory and through the ages remains quite visible in the iconography of Elam and the Iranian mountains." More influential than Der on the Sumerian cults was likely Ninazu's own city which also was close to the Iranian border - Ešhnunna. While the god also had a smaller cult center in the south of Sumer called Enegi, Wiggermann relates that the Ophidian lore that is attestable from the site of Enegi "is written mostly in foreign languages and appears to have been imported", meaning that the snake god ideology at Enegi is again part of the greater influx from Der, Ešhnunna, and ultimately from the east.

The Muš huššu/ The mušhuššu was the dragon of Ninazu, city god of Enegi and Ešnunna, and of his son Ningišzida. From Old Akkadian times onwards (2400 BC), Ninazu was succeeded in Ešnunna by Tišpak, whose traits mainly derive from Ninazu, including the association with muš huššu. It is from Tišpak that the muš huššu was taken, and given to Marduk, after the defeat of Ešnunna by Hammurabi (1900 BC). Muš huššu translates to "furious snake" or "aweful snake", the creature had in earlier times lion parts and dragon parts, but over time "the lion parts are progressively replaced by snake parts" and the creature is called a "snake-dragon" by modern scholars. Wiggermann characterizes the Muš huššu as "perhaps an angel of death, killing with his venom" which is entirely consistent with an the behavior of snake creatures such as the ušum/bašhmu, the enemy of the exorcist in early incantation, or the ušumgal who like the Muš huššu is also a serpentine chaos monster, defeated by the warrior god (defeated opponents often enter the service of the gods.) It is worth emphasizing that nothing seems quite black or white with Mesopotamian religion, and that which was feared was also respected and so in some situations it was counted on as a protective force - the Muš huššu was used in some periods as an Apotropaic figure, on plaques or palace walls, to ward off evil doers. It's not that it was incapable of evil doing itself - but if properly respected and revered would possibly unleash its venom on an uncontained enemy. The dragon is also mentioned in a hymn to the building of Ningirsu's temple, a temple built in Lagash by Gudea (whose personal god was Ningishzida.) Below I have quoted part of that hymn, and I have pointed out the names of the snakes mentioned in [square brackets]: etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.2.1.7&display=Crit&charenc=gcirc&lineid=t217.p84#t217.p84722-729. The cedar doors installed in the house are Iškur roaring above. The locks of the E-ninnu are bisons, its door-pivots are lions, from its bolts horned vipers [ušum/bašmu] and fierce snakes [muš huššu] are hissing at wild bulls. Its jambs, against which the door leaves close, are young lions and panthers lying on their paws.

730-737. The shining roof-beam nails hammered into the house are dragons [ušum/bašmu] gripping a victim. The shining ropes attached to the doors are holy Niraḫ [Niraḫ] parting the abzu. Its …… is pure like Keš and Aratta, its …… is a fierce lion keeping an eye on the Land; nobody going alone can pass in front of it.

Wiggermann writes that after the defeat of Ešhnunna by Marduk, and that god's assumption of the Muš huššu, Ninazu and Tišpak became associated with other snakes and dragons (ušum/bašmu, ušumgallu). The similarity between these creatures is attested again by this exchange, while at the same time it emphasizes that they are separate entities. When a god loses one, he has the other instead. Wiggermann does not state that Ningishzida lost association with the Muš huššu as a result of the Babylonian campaign in Ešhnunna or that he became associated with the Ušum as a result (as the case with Ninazu).. In fact, I believe Ningishzida was associated with both creature at the same time, if we look to the Gudea era where the god is symbolized by 2 Mus huššu which flank coiled snakes (the Gudea cup) , or when the god is in anthropomorphic form presenting Gudea to another god, the horned snakes (ušum) are at his shoulders - thus both creatures relate equally to the deity at that time. What is curious, is a statement of the authors that reads: "Ningishzida, the son of Ninazu, is associated with the [Muš huššu]; his proper animal, however, is the snake (d)Niraḫ." The snake Niraḫ, as we see in the above hymn, is connected with the Abzu and that environ, the semi-mythical underground fresh waters of the god Enki. It is distinct, or at least somewhat distinct, from the Ušum. This information, that Niraḫ should be Ningishzida's animal, is for me somewhat unexpected - the ušum/bašmu is solidly placed as the snake at the god's shoulders (see last post). I suspect the association with Niraḫ may be somewhat earlier.. while I am able to detail Niraḫ to some extent currently, I'm not at this time able to explain Wiggermann's statement or how he connects the snake with Ningishzida. So I will make a post at enenuru and get back with an answer, hopefully. Best Regards |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Aug 12, 2009 10:00:56 GMT -5

Additional Ophidian Lore: In the above post, I found it somewhat curious that Wiggermann was able to state Niraḫ as "the proper animal of Ningishzida" in his book Mesopotamian Protective Spirits. Wiggermann is a senior lecturer in Assyriology from Free university, Amsterdam, and I have referred to him extensively as he is a scholar with specific learning in Mesopotamian iconography, magic and has made perhaps the largest study into the religious concepts surrounding snakes. He should probably be considered the authority on these questions therefore. That said, his comment which places Niraḫ as the proper animal of Ningishzida troubles me - given that the author did not expand on the point or include a footnote, I was unable to explain his justification. I have since requested a friend from enenuru (Madness) who has more articles from the same author to review further material and he has kindly replied.. Madness relays that in another article of Wiggermann's.. " it is mentioned that the two [Ningishzida and Niraḫ] are associated in late texts, pointing to a temple hymn in Babylonian Topographical Texts, p. 47, with commentary on pp. 274-275.

But it is also stated that Ningišzida is associated with the mušhuššu and with bašmu; he is in fact equated with the mušhuššu and ušumgal a Sumerian hymn. I do not believe it is correct to place Niraḫ as the proper animal of Ningišzida." In other words, Wiggermann does have some basis for associating Ningishzida with Niraḫ - it appears that some late hymns, the god is paired with this snake. However, given that this appears to be a late association with limited attestations, we at this time feel Wiggermann was overstating with the "proper animal" comment, and that the Ušum/bašmu, the horned snake at his shoulders which is associated with the god in earlier Sumerian hymns, would better fit that designation. The Muš huššu is a sort of Heraldic animal which the god shares in common with his father Ninazu. As for the Sumerian hymn associating Ningishzida with the Muš huššu and ušumgal that is a Babal to Ningishzida (Ningishzida B): etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.4.19.2&display=Crit&charenc=gcirc&lineid=t4192.p1" My king, Lord Ningišzida, imbued with great savage awesomeness! Hero, falcon preying on the gods, my king -- dignified, with sparkling eyes, fully equipped with arrows and quiver, impetuous leopard, murderous, howling [muš ḫuššu], {……} " A variant of the same hymn reads instead: " dragon [ušumgal] snarling (?) in the lagoon, raging storm {reaching} .. all people!" Der Again/ At this point it may be worth it to recall the city of Der, which was in North eastern Mesopotamia and bordered modern day Iran, acting as a transfer point for the some religious tenets of the east, particularly in the case of snake gods. We see this suggested for example in a small Sumerian hymn to the temple at Der, which tells about the iconography on the walls of that city: 416-423. O Der... , taking extreme care of decisions, ……, on your awesome and radiant gate a decoration displays a horned viper [Ušum/bašmu] and a mušḫuš [Muš huššu] embracing. Your prince, a leader of the gods, fit for giving counsel and grand speech, the son of Uraš who knows thoroughly the true divine powers of princeship, Ištaran, the …… sovereign of heaven, has erected a house in your precinct, O E-dim-gal-kalama (House which is the great pole of the Land), and taken his seat upon your dais. 424. 8 lines: the house of Ištaran in Der. Ištaran was the city god of Der and one who remains unfortunately quite enigmatic. By his name (a combination of Ištar and AN) scholars deduce that that he was an astral deity who at some point merged with cthonic snake god religion - an odd combination which may attest to incoming influence from the east. The god is known to have been a god of justice, among other qualities. While the Muš huššu and the ušum were possibly on the walls of Der somewhat before the same came into use in the snake god cult centers to the south, when later Ningishzida's cult enjoyed a high point after Gudea's patronage, we see Ištaran equated briefly with the younger god (in a sense subordinating his character). An example is in the myth "Ningishzida's journey to the nether world" when the sister call to him, calling him Ištaran: etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.7.3&display=Crit&charenc=gcirc&lineid=t173.p2#t173.p215-19: .... " Ištaran of the bright visage, let me sail away with you" On Niraḫ/ Ištaran's son and messenger was Niraḫ, who also served as the iconic representation of the god - according to C. Woods late traditions even "considered the two gods to have been so close as to be identical." Niraḫ is depicted as a snake god with an anthropomorphic upper body and the lower body of a snake. This image may therefore stand for Niraḫ, or for Ištaran - (picture below) img295.imageshack.us/i/4dsq8.jpg/Woods says that "occasionally, he may hold his tail which may terminate in a dragon's or a snake's head and he is portrayed with either a single-horned headdress indicative of divinity or with a flat cap." In some types of iconography such as the Kudurru stones (boundary markers) Niraḫ appears as a naturalistic snake and not half human. Niraḫ is spelt in cuneiform by the signs d.MUŠ, which means "deified Snake". Experts reading the name must use caution as it can mean one of two snakes, Niraḫ who we have been discussing, or Irhan - Irhan is the personification of the Euphrates river, which winds its way through the country as a snake and renews itself in wet seasons (as a snake sheds it's skin.) Irhan is sometimes pictured in cosmological scenes, wrapped around the stars, sun and moon - in these scenes scholars speculate that he is the cosmic river, thought to encircle the Mesopotamian cosmos. Niraḫ, on the other hand, seems to have had more specific connection to the Abzu, the underground waters which supplied all fresh waters in Sumer (including the Euphrates). He was especially associated with objects parting the waters of the Abzu, perhaps based on observation of snakes which swam in the marshes: In Enki's jouney to Nibru he serves as Enki's punting pole (reminding us of that deities connection with snakes). In a tale of Lugalbanda, the Anzud bird is told "Your breast as you fly is like Niraḫ parting the waters!" In the building of Ningirsu's temple we read "The shining ropes attached to the doors are holy Niraḫ parting the abzu." The snake in any case may have had something to do with transport or travel from the Abzu to the mundane realm. |

|

|

|

Post by creed on Aug 17, 2009 5:42:08 GMT -5

From this board and others I gather that Ng is popular now for reasons I will not list assuming that you know them. But from what reading I have done on the subject it would seem that Enki seems to be more fitting in regard to what people are trying too fit Ng into.

It is with Enki that we have the definition of Great Magician and giver of the 'Me' too civilization, also he is associated with the double helix snake. Why is he over-looked and such regard put on to Ng?

Edit: I am aware that two of the above associations can also be attributed to Ng - but are they not originally placed with Enki?

Also, Enki is portrayed as the balance of Enlil - Enlil, in my opinion, the prototype for God in certain passages of the Old Testament - well at least the ones where God wants to kick some ass. And as you are aware - we have Enki standing up to the Ruler on behalf of humanity. A veritable 'Light Bringer' for the masses...

|

|

|

|

Post by madness on Aug 20, 2009 1:08:25 GMT -5

Hi creed > it would seem that Enki seems to be more fitting in regard to what people are trying too fit Ng into < I'll assume here that you are referring to the serpent in Eden? I don't see how confusion could arise between the two gods. The one (Ningišzida) is a snake god, associated with trees, death, and the Netherworld. The other (Enki) is not a snake god by any means, neither is he a god of the Netherworld. They seem quite distinct to me... If we're going to "fit" Mesopotamian gods into West Semitic parallels, we may as well look at the available evidence. Fortunately, a pantheon list from Ugarit makes this easy (but should be used with some caution, as it is a speculative text). John F. Healey, The Akkadian "Pantheon" List from Ugarit, SEL 2. You can download this article: www.ieiop.com/www.ieiop.com/publicaciones/listado.php?idcategoria=56Here we see that Ea (=Enki) is equivalent to the Ugaritic god ktr (=Kothar-wa-Hasis), whose name means "Skillful-and-Wise." Wikipedia has a decent explanation of this god: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kothar-wa-Khasisen.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baal_cycleKothar's craftiness and his role as a magician easily compares with Enki. And as we see in the Baal cycle, the role of Kothar in the battle is similar to the usual role of Enki in battle myths (i.e. assisting the protagonist in defeating the monster). Thus we have no reason to identify Enki with any West Semitic deity other than ktr. Also in the pantheon list, Ašratu is equivalent to 'atrt (=Asherah). As I have already noted in the Asherah thread, Ašratu seems to be another name for Geštinanna/Bēlet-ṣēri, whose name reads geš+tin "tree + life" and she is the wife of Ningišzida. Leslie S. Wilson says, in The Serpent Symbol in the Ancient Near East (pp. 207-210), that the garden of Eden story is actually a mythological explanation of Solomon and his sympathy for Asherah worship, so... I hope this is of some help. Feel free to repost in other boards if needed. |

|

|

|

Post by madness on Aug 20, 2009 4:16:54 GMT -5

Further insight: Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, pp. 126, 275, 490.

|

|

|

|

Post by ninurta2008 on Aug 20, 2009 16:55:05 GMT -5

Though if you point to what they pointed two between the cultures, which I don't see why they chose the sumerian one, the greek one is closer to the biblical tradition. But based on what they did, when they compared the stories, assuming they are correct (In which they were not, or at least there is nothing to suggest there were), that the stories originated from the same story, here is who the "equivalents" in the story could be:

Ea = God, though a much nicer more forgiving one

Ningishzida and Damuzi = The serpent

Adapa = Eve, and its obvious how rediculous equating the two would be

|

|

|

|

Post by madness on Jan 3, 2010 3:18:44 GMT -5

Yes well, I now feel that we should take a step back from such panbabylonism; the Genesis story in all likelihood developed out of Canaanite beliefs involving Asherah and Nahash, there's no need to throw Mesopotamian myth into the fray (except for, and only for, comparative purposes, without implying that one is derived from the other unless derivation can be proven).

|

|

|

|

Post by madness on Jan 5, 2010 0:17:56 GMT -5

William Hayes Ward examined cylinders that were in the J. P. Morgan library in New York. The hematite cylinder above he believed represents the deity Ningišzida. [1] Cylinders and Other Ancient Oriental Seals in the Library of J. Pierpont Morgan (1909), p. 63f. no. 118. [2] The Seal Cylinders of Western Asia (1910), p. 129. DOWNLOAD HEREThe deity has two serpents arising from his shoulders which is characteristic of Ningišzida, but most unique about this image is the coiling of the serpents around the body of the deity. In [1] Ward even suggests that "a deity such as this may well be the source of the Mithraic figure of a god entwined with serpents, and of a Cretan serpent deity." So far I'm at a loss trying to find more recent studies that deal with this cylinder. Need more details about it, I would certainly like to know its provenance and date (though Ward gives a possible date of 2000 BC). Perhaps we have found a proto-Aion? img35.imageshack.us/i/aionbk.jpg/EDIT: I did not realise this was already pointed out by sheshki above reply #116. |

|