david

dubĝal (scribes assistent)

Posts: 43

|

Post by david on Nov 14, 2007 10:25:38 GMT -5

I can't say anything about the post, but I really think your drawing is really cool, it looks good.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Nov 17, 2007 0:23:23 GMT -5

Well L.H., This is certainly one Ive been figuring on getting to, and this would be a good pretext. Ning̃išhzida (I'm using the rendering of the name as it appears in a recent scholarly publication. But my tilde wont get over my g as its supposed to..) is a deity who has incurred much speculation and comparison I notice from a moments googleing around. There would appear to be three main source's for perspective on this deity: 1. People who take the sign on the ambulance and work backwards in a horrible sequence of comparison 2. Thorkild Jacobsen 3. Papers and articles primarily from sometime around 1902 which focus on the instance of Gishzida in the story of Adapa. I enjoy Jacobsen, and your understanding accords well there. Thats who I lean on in any case, I dont think it would be wise to draw from 1 or 3. It would be beneficial to have much more still, I hope this thread will take the form of a study aid for Ning̃išhzida therefore, and ultimately it should answer your above question. Though I can say I am skeptical in many places about what is quoted above. To start with I am looking through a book " The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia" by A.R George [1993] this book is a wonderful resource for temples. With careful referencing and some difficulty, Cohens accompanying notes may provide further leads. The author in this book has some 1449 temple entries, the following 8 correspond to our Deity: Temples: - 102. é.bàd.bar.ra, "House, Outer Wall," temple of Ning̃išhzida at Lagaš-Girsu (G with tilde) in Ur III times (MVN VI 301, obv. ii 20: offering list)

- 408. (é).g̃iš.bàn.da, "House of Gišbanda," (G - tilde) temple of Ning̃išhzida at Gišbanda, often paired with Ninazu (MSL XI, p.142, viii 42; above, p.4, IM 96881, iii'11?; Temple Hymns 190; Lamentation over Sumer and Ur 210-11), also known from the cultic lament edin.na ú.sag̃.g̃á (Cohen, Lamentations, pp. 676, 154; 684, 33).

- 434. é.gu.za.lá.maḫ;, "House of the Exalted Chamberlain." temple of Ning̃išhzida at Babylon (Topog Texts no. 1 = Tintir IV 13). Written é.gu.za, alim.maḫ, "House, Throne of the Exalted Bison," in a mythological text (BM unpub, courtesty Lambert).

- 593. ki.gal.la, "Great Place," seat of Ning̃išhzida in é.sag̃,íl at Babylon (Topog Texts no.1 = Tintir II 24).

- 877. é.níg̃.gi.na, "House of Truth," temple of Ning̃išhzida at Ur, rebuilt by Sin.iqīsam [unable to render accents] (Frayne, RIME 4, p.196, 8) and Rīim-Sin (ibid., p.285,41)

Temples attested to in text without accompanying names: - 1378. Ning̃išhzida: chapel in é.an.na at Uruk, built by Anam and Merodachbaladam (Gadd, Iraq 15 [1953], pp. 123ff.)

- 1379. Ning̃išhzida: temple at Girsu [tilde] built by Gudea (Steible FAOS 9/1, Stat. I, iii 9; P, iii 10; Gud 67-68; etc)

- 1380. Ning̃išhzida: sanctuary at Isin in OB documents, Kraus, JSC 4 (1949), p.60.

The Temple Hymns, etcsl t.4.80.1, contain this hymn which Cohen notes as corresponding to temple 408 (according to the incidental numbering of that book.) "187-196. O primeval place, deep mountain founded in an artful fashion, shrine, terrifying place lying in a pasture, a dread whose lofty ways none can fathom, Ĝišbanda, neck-stock, meshed net, shackles of the great underworld from which none can escape, your exterior is raised up, prominent like a snare, your interior is where the sun rises, endowed with wide-spreading plenty. Your prince is the prince who stretches out his pure hand, the holy one of heaven, with luxuriant and abundant hair hanging at his back, Lord Ninĝišzida. Ninĝišzida has erected a house in your precinct, O Ĝišbanda, and taken his seat upon your dais. 197. 10 lines: the house of Ninĝišzida in Ĝišbanda. "Articles to note (and access when available): Ningišzida and Ninazimua by J.A. Black, Orientalia 2004 vol. 73, no2, pp. 215-227 issn: 0030-5367 Three Hymns to the God Ningiszida by AW SJOBERG - Studia Orientalia Helsinki, 1975 - 1975, vol. 46, pp. 301-322 P.S. L.H, I'll have to ask you about art sometime. cheers. |

|

|

|

Post by xuchilpaba on Nov 24, 2007 11:03:12 GMT -5

>3. Papers and articles primarily from sometime around 1902 which focus on the instance of Gishzida in the story of Adapa. Isn't Adapa what many scholar take to be the origins of the biblical Adam? So Ningishzidda is the serpent or related in the tree in eden and Adapa would have been "Adam"?  |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Nov 28, 2007 17:20:25 GMT -5

dnin.giš.zid.da G. Leick's 1991 book " A Dictionary of Ancient Near East Mythology" gives a fair sampling of brief useful entries, her entry for Ning̃išhzida (p.131) presents a reasonable framework to start with: "The meaning of the name dnin.giš.zid.da, 'Lord of the good tree', is obscure (although Jacobsen 1973, 7, reads it as: 'the power of the tree to draw substance through its roots'). He was an Underworld deity; the Sumerian Temple-Hymn (Sjoberg, Bergmann, No.15) describes his 'house' in Gišbanda as 'a dark cellar, (an) awe-inspiring place'; maybe it had a subterranaen sanctuary, Ning̃išhzida himself is the 'prince who stretches his pure hand to heaven, with luxuriant and abundant hair (flowing down his) back'. In the Neo-Sumerian period, Gudea introduced him into the Lagash pantheon as his personnel god, whom he loved 'above all others'. He was also worshipped in Shuruppak, Ur, Umma, Larsa, Nippur and Uruk. Ning̃išhzida's cthonian aspects are confirmed by the god-list An- Anum. His emblem was the horned serpent and Gilgameš see's him officiating in the underworld ( Gilgameš, Enkidu and the Netherworld). He was sometimes identifed with Damu, the dying god, and was mourned by his sisters. As a (temporarily) absent god in the company of Dumuzi, he was found by Adapa at An's gate in heaven. This close connection with Dumuzi and fertility is further underlined by the fact that his wife was Geštinanna, Dumuzi's sister. His astronomical correlate was the Hydra. "(Leick gives her references as: -The God Ningizzida (1934) a book By Elizabeth Douglas Van Buren (An early specialist of Iconography)/ -Roux, G. (1961) 'Adapa et le vent', Revue d'Assyriologie 55) From " The Treasure of Darkness" (Jacobsen 1973, 7 as cited above) and " Toward the Image of Tammuz" Jacobsen/Moran 1970 Jacobsen opens this book [1976] with a discussion of the terms used in the study to elucidate and define Mesopotamian religion and in speaking on "name and form", he states that in earliest Mesopotamia the name and form of Numinous (feel/presence of the Divine) tended simply to be the name and form of the phenomena in which the power seemed to reveal itself; however the form given to a Numinous encounter may adjust to the content revealed in it - as an example Jacobsen use's Ning̃išhzida: "The god Ning̃išhzida, "Lord of the good tree," who represented the numinous power in trees to draw nourishment and to grow, had as his basic form that of the tree's trunk and roots; however, the winding roots, embodiments of living supernatural power, free themselves from the trunk and become live serpents entwined around it. "Southern Orchards- From Uruk to Ur there are three different groups of early economies and thier gods, according to the author: Cities of the marshlander's family of gods decended from Enki ranged from Eridu and Ku'ar to Nina in the east; cities of the Herdsmans family of gods descended from Nanna in Ur extending northwards; and lastly "there is a group of cities that have city-gods belonging to still a third family of gods descended from Ninazu. The gods of this group all have pronounced cthonian character as powers of the netherworld, and several of them appear closely connected with trees and vegetation." Genealogy- Along the lower Euphrates Jacobsen relays, there are a mix of deities attributable to cowherds and orchardmen - its in the latter group that "Ning̃išhzida, the "Lord of the Good Tree", Ninazu the "Lord knowing the waters", and Damu, "the child," power in the sap that rises in trees and bushes in the spring." are included(1976). It seems almost paradoxical for a father to be identified or to absorb mythological aspects from a son, but still the genealogical tradition Jacobsen outlines is as follows:

Ninazu > son of Ereskigal [variant tradition, of Enlil/Ninlil]> Ninazu is the Spouse of Ningirda (a daughter of Enki)

Ningishzida> son of Ninazu/Ningirda > Ningishzida is the Spouse of Ninazimua*

Damu> son of Ningishzida/Ninazimua ( *note Leick's mentioning of a variant tradition above with spouse as Geštinanna) Identification with Damu "Dying Gods of Fertility" On page 26 (1976), Dumuzi, whose cult is attested already in the forth millenium, is described as essentially "the élan vital of new life in nature, vegtable and animal, a will and power in it that brings it about." Dumuzi is however of a decidedly multi-faceted in nature, and this becomes apparent when the god's differing aspects are given as: - Amaushumgalanna, "the one great source of date clusters"

- Dumuzi the shepherd (amoung shepherd or cowherds)

- Dumuzi of the grain (farmers) and finally

- Damu The child ("This form which may originally have been independent of the Dumuzi cult, still preserves in a good many distinctive traits.")

[/color] [/li][/ul] Textual evidence attests to the fact that the cult of Damu "influenced and in time blended with the very similiar cult of Dumuzi the shepherd." [ 1970] Jacobsen understands Damu to represent the power in the rising sap, and this deity's relation to Dumuzi and depiction as a dying god is important for consideration of Ning̃išhzida in myth - as indeed the later would 'sometimes be identifed' with Damu. The reasons for this identification if Jacobsen is accurate, are more apparent when both Damu and Ning̃išhzida are understood as deities of the orchardman on the lower Euphrates, and both are deities whose primary Numinous power was in the fertility and new life of tree's and vegetation - their dying aspect (part of what brings Dumuzi, Damu and Ningishzida together) must be attributable to yearly waning in the dry season. The power of Damu is further detailed by the author "As a power for fertility and new life the god would appear to have been specifically the power in the life-giving waters as they return in springtime in the rivers, rise in the ground, and enter trees and plants as sap, for when in the cult Damu's mother and sister seek him he has died in the trees and rushes and the search moves through a world that has become the nether world, dry and lifeless. When the god is found and returns, it is from the river that he comes back. The original setting of the Damu cult would seem to have been essentially horticultural economy of the settlements along the lower Euphrates south of Uruk. Damu's home town is Girsu (Eme-sal Mersi) on the Euphrates and in the litany charactoristic of the Damu laments he is identified with a number of neighboring deities - all cthonic in character - such as Ningishzida ("Lord of the good tree" married dá-zi-mú-a, "Well grown branch") of Gishbanda, Ninazu of Enegir (cf. vsn Dijk, Sumerisch Gotterlider (Hiedelberg, 1960) 2: pp.57-80), Sataran of Etummal, Alla, lord of the net, etc. " [1 970, p.324n8] Survey of the Texts : (With appreciation to ETCSL) Within the Dying gods of fertility sphere Ninĝišzida's journey to the nether world:In the Netherworld The death of Gilgameš: c.1.8.1.3 - He set out their presents for Ninĝišzida and Dumuzid The death of Ur-Namma (Ur-Namma A): c.2.4.1.1 - To the valiant warrior Ninĝišzida, in his palace, the shepherd Ur-Namma offered a chariot with …… An elegy on the death of Nannaya - May Lord Ninĝišzida …… the house ……. May the mighty Gilgameš …… health for you

Taken as the personal god of Gudea

The building of Ninĝirsu's temple - The daylight that had risen for you on the horizon is your personal god Ninĝišzida Hymns to Ninĝišzida A balbale to Ninĝišzida (Ninĝišzida A): c.4.19.1- This Hymn helps to establish character, outside of comparisons with Damu etc. - Raised in the abzu, and called an išib priest - this is an early word for incantation specialist. - Instances of 'Royal Praise' in this hymn not as helpful as these are generic terms used to address most all deities. - Given as the son of Ningirada and Ninazu A balbale to Ninĝišzida (Ninĝišzida B): c.4.19.2 - The existence of a tradition of Ninĝišzida as incantation specialist is suggested further here "Lord, your mouth is that of {a pure magician} {(1 ms. has instead:) a snake with a great tongue, a magician} {(1 ms. has instead:) a poisonous snake}" - Perhaps Madness, Meine Freund, you might cross reference YOS XI for me to see why I remember him being mentioned there. It should be noted that Ninĝišzida is not a major feature in the incantation lore despite this piece of Hymnology howeever. A hymn to Ninĝišzida (Ninĝišzida C)

A balbale (?) to Ninĝišzida (Ninĝišzida DOther: Enki and Ninḫursaĝa: c.1.1.1 Azimua shall marry Ninĝišzida The lament for Sumer and Urim: c.2.2.3- Ninĝišzida took an unfamiliar path away from Ĝišbanda. Azimua, the queen of the city, wept bitter tears. The temple hymns: c.4.80.1- Your prince is the prince who stretches out his pure hand, the holy one of heaven, with luxuriant and abundant hair hanging at his back, Lord Ninĝišzida.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Nov 29, 2007 13:18:32 GMT -5

Lady H- Frankfort (1897-1954) was an important figure in early ANE studies and I believe had something to due with establishing a chronological framework. He also wrote on Mesopotamian religion, and its interesting that Frankfort produced in 1946 a book called "The intellectual adventures of man" with T. Jacobsen, which was later renamed 'Before Philosophy' - the book dealt with his concepts of "mytho-poetic thinking". He and Jacobsen seem likely to have alot in common therefore. The excerpt from Frankforts Chap 18 you quote above "One single rhythm flows through the life of nature and of man......." is quite cognizant of some of Jacobsen's views that I outlined in my reply, and Frankfort could probably be taken as a forerunner here. I would consider Jacobsen's portrait of "Dying gods of Fertility" as the extent to which Ningishzida should be identified with other deities over Frankforts 'one concept behind Ningirsu, Ningishzida etc..' We will probably not be informed of the latest development in this research until accessing the below however: Ningišzida and Ninazimua by J.A. Black, Orientalia 2004 vol. 73, no2, pp. 215-227 issn: 0030-5367

Your quote from "Sumer the Dawn of art" by Parrot seems fine, with iconography of any sort (not usually my area) it seems to be highly interpretative, even to the experts (especially when there is no accompanying inscription). Also interpretation on some piece's seem to vary widely according to the progress of ANE studies.  There appears to be an inscription on this cup, and Leick writes in 1991 (Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology) that the libation cup drawn above is "dedicated by Gudea, rule of Lagash, to his god Ningishzida. The symbolism on this vessel combines the ancient auspicious motif of entwined serpents with an apotopaic demonic being, eagle clawed, winged and with a feline body. The creature holds a long staff, the meaning of which is obscure, and wears a horned cap. He was probably closely associated with Ningishzida himself. Ca 22nd century BC. Louve. " This accords very well with what Parrot stated in 1961.

So far as the original question you asked, after surveying some sources, we could address that. Part of what the original poster stated was: "Ningishzidda, or Ng was the wife and mother of Dumuzi" This logic train seems in so far as Ive seen, to be basically inaccurate before it even goes anywhere. While Ningishzida had as a fundamental aspect a fertilizing principal, this does not make him a mother goddess. While he was conceptually related to Dumuzi and even identified with wth the latter as a 'Dying god of fertility', this doesn't make Ningishzida that gods mother or wife. And beyond abundant indication in the myths of Ningishzida as male (I dont know any text that suggests otherwise) there is also the philological comment which Amarsin contributed earlier. (See the 'Ningishzidda and Gizzida names?' thread): "The Sumerian "nin" means, in general, "queen" and is a common first element in Sumerian divine names. However, as this example (and many others) show, the "nin" must also refer to the masculine. Nin-gišzida is the son of Nin-azu, and so decidedly male. (Indeed, Nin-azu is Nin-gišzida's father, while his wife (and so Nin-gišzida's mother) is Nin-girida!) "Besides a rigid view of nin as female, which as we see here is incorrect, the layman may arrive at Ningishzida as female or even as a mothergoddess by reading the below link, which I think seems pretty close to what the original poster was saying Lady H. www.mazzaroth.com/ChapterThree/TowerOfBabel.htmHowever I dont believe Jim Cromwell is in anyways textually or factually amenable hrm from what Ive sifted through. So the question was "In your (scholarly) opinion, is the above paragraph in quotes true or not true?" I dont have a scholarly opinion, but no. More to come on Ningishzida! I love an obscure deity  |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Feb 13, 2008 1:58:15 GMT -5

Ningiszida's Boat-Ride to Hades by T. Jacobsen and B. Alster (Notes from the above article which is contained within the book "Wisdom, Gods and Literature: Studies in Assyriology in Honour of W.G. Lambert." Note as the article's title may suggest, this article treats the myth "Ninĝišzida's journey to the nether world".) On the Snake Imagery of the God (pg.315) : "....this seeming inconsistency of a god of trees who is also a god of serpents resolves itself once it is realized that the ancients considered the roots of trees in some ways "identical" with serpents....That they did so consider them is clear from the sign for tree root, arina, which consists of two crossed signs for serpent (MUŠ). A variant sign adds the sign for tree, g̃iš. In its earlier pictographic form this sign-group would have constituted a slightly abbreviated form of the 'caduceus." which thus shows itself as representing the trunk of a tree with its roots in sepent form. In fact, the representations of Ningišzida on Gudea's monuments may well be a humanized version of the "caduceus," the serpents' heads remain, but their bodies and the tree trunk having been made into a human figure." On Gudea's vase - - What is this vase? Jacobsen Comments: " On monuments he is pictured with serpents heads protruding from his shoulders and, in his preanthropomorphic form, as a "caduceus," a pole around which two symmetrical serpents wind themselves." (an accompaning note refers specifally to the vase and reads: "...The relief shows the gate of the god's cella through which the cult image is visible." The read is referred to L. Heuzeu, Catalogue des antiquites chaldiennes (Paris, 1902, no. 125 for an image. Does Jacobsen mean Gudea's cup I wonder? (See Nov.29 above.) I dont see how this is a gate, seems more link two semi-anthropomorphic beings holding a pole. ) The Mythology of the God: Jacobsen relays that "The mythology of Ningišzida is, as already mentioned, greatly influenced by that of the dying gods of vegetation, so much so that it reflects little, if anything of his basic nature." (See my posting on Nov. 28th above about the identification with Damu.) The author continues "As god of tree roots, Ningišzida naturally would have and, one would think, always would have had his abode underground, that is, in the Nether World. In the myths about him, though, he is not thus represented but rather as an Upper World deity who was taken forcibly down below. This, it will be recognized, is the standard pattern for the myths about the dying gods of vegetation." The myth dealt with here, Ninĝišzida's journey to the nether world. The basic plot reads as the capturing of Ningišzida by demonic forces of the Netherworld, who drag him off to the Netherworld - in effect meaning his death. He is lamented and pursued by his loyal sister but to no avail, however, when he arrives there "he is unexpectedly freed and attended to as a member of the corps of "throne-bearers" of the Nether World." As for why, Jacobsen comments "Why the mythopoeic imagination should have given him this particular office is not apparent." However this function of throne-bearing may be more broadly interpreted - while originally the throne bearer was carrier of the the chair of the ruler, "its seems probably...that the hefty throne-bearer will have served also as bodyguard, for with time the office came to imply police powers, guarding evildoers. This was Ningišzida's function in the Nether World." The challenge to understand Ningišzida in myth is therefore this: A deity who you'd expect to always be in the underworld, but is depicted as an upperworld deity forcibly brought there, perhaps due to his association with the dying gods; And once there he is given a position, the mythopoetic logic of which 'is not apparent'. And so his basic nature is perhaps to be reinterpreted by these assimulations.

|

|

|

|

Post by saharda on Feb 25, 2008 14:54:01 GMT -5

I haven't completely read the thread, but I thought I would make a few comments based upon my understanding now before I get to the end and forget that I was going to comment.

Ningishzida: He is male, god of the dawn and the dusk, and iconicly is shown with two snakes coming out of his shoulders. Much like a sun loving version of the comic book character Darkness. He is the son of the god Ninazu who is in turn the son of the fallen Bull of Heaven and Ereshkigal. There are other traditions as to his descent, but I find that this one makes sense.

|

|

|

|

Post by saharda on Feb 25, 2008 14:57:35 GMT -5

Your picture is a technically well done one. The colors and the forms are fantastic. I should note that a lot of the elements are incongruous however. The focal point around the Yin Yang for example is something I don't quite get. As for the scorpion demons, I don't really understand their significance and their forms are odd.

|

|

|

|

Post by saharda on Feb 25, 2008 15:07:44 GMT -5

oh and a final note, "Ng" is something I have run across once as a demon. I believe it may be lovecraftian in origin, or otherwise from some modern source. There is so much bad information out there that relates to Ningishzida that you would be amazed.

|

|

|

|

Post by monkeyblood on Mar 18, 2008 6:13:15 GMT -5

I know that now.....Sitchin has written a few books incorporating the premise that Ningishzida is Enki's son,Marduk's brother.I knew that his research can be suspect at times as well as the conclusions he comes to but to make such an careless mistake.......thanks to Madness again for clearing that one up.

|

|

|

|

Post by madness on Apr 11, 2008 21:04:39 GMT -5

although the cup at Lagash is "only" 7,000 years old

Gudea (of whose inscription appears on the vase) reigned for about 20 years during the second dynasty of Lagash, dating towards the end of the third millenium. The vase would not be older than some 4000 odd years.

Where did you get 7000 from?

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Apr 24, 2008 3:01:01 GMT -5

Naomi: Hey - Very nice! ;] Too mail you direct about latest art piece. In the meanwhile must type up following note while still at library.

Mr. Yoshikawa's Contribution to the Ningishzida thread:

I have typed below the notes of Yoshikawa, a studious Sumerian scholar from Japan, whose notes have been digitized for the world here. A new trick I have just learned is, upon entering the search engine, click the bottom button "Sumerian character keyboard." After this, enter what is in quotes "d." - this will tell the system to search for entries with the dingir, in effect you get a list of gods, each clickible and containing Yoshikawa's notes. It is also a SOB to search for Ningishzida's name, and even here I had tried every which way to enter it - I was able to find it only by using this new trick and only by entering the following in the same field on the Sumerian character keyboard: search "d.N" (N must be capitalized, scroll to find.) These digitized notes are those of an ANE scholar, a recognized Assyriologist, and are something somewhat we may not immiediatly appreciate, and in alot of cases may never be able to utilize - yet in those few instance we do, there will be rare insight gained. All of these time piece's when arranged together equal the modern understanding of the Sumerian charactorization of Ningishzida. In the below a single format is repeated. a ) Authors name, b ) Publication refers (usually abbreviated e.g. BASOR = Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research) c ) The relevent lines from of text which concern the point made in the given article. -See here for an abbreviation guide- The entry on d.Nin-giš-zi-da reads: d. Nin-giš-za-da - Sumerian Proverbs 1.4

dNin-giš-za-da-ra ga-ti na-an-na-ab-bé-en

(Gordon: Do not say to Ningishzida (a nether-world deity): "Let me live!"

4. cf. Van Buren, Iraq I p1934], pp. 60-89

- Kramer, BASOR SS.1

275) dá-zi-[mú -a dnin]-gišzi-da ha-ba-an-tuk-tuk

"Let Azi[mua] marry [Nin]gišzida,"

- Gudea's personal god. (See Statue s. passim)

- Gudea, Statue M (&N):

II 1)dgeštin-an-na

2) nin-a-bi-mú-a

3) dam-ki-ág

4) dnin-giš-zi-da-ka

5)nin-a-ni

III, 1) gu-dé-a

- Mercer, JSOR 10. No. 2

1)dnin-giš-zi-da 2)dingir-ra-ne

3)gu-dè-a ~

- Parr, JCS 26/2 No.10

1) 1 udu 2)dnin-giš-zi-da-šè

- Gud. cyl. B XXIII

18) dsuen(?) dnin-giš-zi-da dumu-KA-an-na-kam

- Ib. XXIV

7) [g]ù-dé-a dumu-dnin-giš-zi-da-na

- See Sjoberg, Three hymns to the god Ningišzida, Solomon - Ftestschrift, p.301ff.

- Sauren, Wer Genius der sonne und der stal des ASKlepies, 1ff.

- Perlov, Mesopotamia 8, p.77, 8.

- Karki, STOR 49, p.171. VET 8, 85

1) dnin-giš-zi-da ur-sag i-ši-im disag-ki-bi ka-hu-hu-ul ~

- Lafont, DAS 50 .passim

i,11) máš ú-šem-ma-dnin-giš-zi-da

ii, 16) máš gišgigir-dnin-giš-zi-da

vi,18) máš ú-šem-ma-dnin-giš-zi-da

x, 9) máš ú-šem-ma-dnin-giš-zi-da

13) máš gišdùr-dnin-giš-zi-da

- Krebernik, ZA 676/II,p.128,S.V.

- OECT XIII, p.51, S.V.

copy á, é, í, ú and à, è, ì, ù also š, ḫ, g̃, ĝ Š, Ĝ, paste |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on May 7, 2008 4:36:19 GMT -5

Peeking at Transtigiridan Snake Gods In Black and Greens (soon to be classic) book, "Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia", they write briefly on the Muš-huššu, the snake demon. In that short description, interesting to us here, they allude to a work of scholarship that has done more to elucidate Mesopotamian snake gods and surrounding iconography than any other to date, they say (p.166): "The complex mythologies and divine associations surrounding the creature have only recently been collected and explained. " They have?? By who, when?! But being a reference book which surveys the so much of the Mesopotamian world, we aren't given a specific reference as to whose work is referred to - Extremely frustrating. I have however seen an answer in another of Greens published works... People have recently heard me yammering about the massive 4 volume collection of scholarly works (128 in all) titled 'Civilizations of the Ancient Near East' (CANE); most likely a staple for students though I have no such privilege. Within are two relevant articles, first, Green's article on Mesopotamian Religious iconography (p. 1837), deals in one part again with the Muš-huššu.. This time, the author has more space and can afford some more detailed citations, along with the mystery author of the esteemed work into the topic of Mesopotamian Snake Gods: "complex mythologies and associations of various gods that involved the creature have been collected and explained by F.A.M Wiggermann " Well well... That actually is alot more freaking helpful! The work we should seek then, when cited in full, is from a book called " Sumerian Gods and their Representations", and in particular, an article by Wiggermann which is entitled " Transtigridian Snake Gods". The book however is elusive and currently out of stock at eisenbrauns. This brings me to the second relevant article in the book I do have, CANE 3, that is namely, "Theologies, Priests, and Worship in Ancient Mesopotamia" by F.A.M Wiggermann (p. 1857). This is not material we are looking for precisely, however, it is by the same genius and it is apparent that he frequently alludes to his work on Snake gods at various points while discussing Mesopotamian Theology..we therefore get a "peek" and some of ideas and conclusions delt it in his " Transtigridian Snake Gods" Below I have extracted various points where Wiggermann touches on Snake gods in CANES 3: Pg. 1860: Wiggermann briefly treats important Mesopotamian deities giving a description of each. His comments on the Snake gods are noteworthy: "The once important chthonic snake god, NINAZU ("Lord Healer"), city god of Eshnunna (Eshnunnak, modern Tell Asmar); his successor as city god of Eshnunna, TISHPAK, his son NINGISHZIDA ("Lord of the True Tree"), not a city god but venerated in a small rural sanctuary; and his neighbor, ISHTARAN, the city god of Der (Tell Aqr), lost their national significance during the first half of the second millennium. "Note: When the author says Ningishzida was not a city god, we might think of Gudea in Lagash; which Lagash was a city, its city god was Ningirsu and not Ningishzida (Gudea's personal god.) By "rural sanctuary" the author may refer to the (é).g̃iš.bàn.da, "House of Gišbanda," , in that local (Gišbanda) though this is a guess. See reply #2 of this post. Pg. 1862: On this page while dealing with Statue and Symbol, the authors descriptions speak to the idea that the early snake gods were part of an earlier mode of Mesopotamian religion, more directly corresponding with nature. he writes: "With the exception of some partly animal-shaped early snake gods, all major gods, whatever their origin in nature, were represented in their temples by anthropomorphic statures... "And later: "Nature and its cycles did not lose their religious significance but appeared, reframed by the anthropomorphic cult, as objects and processes managed by divine landowners to serve their needs. An ancient cult more directly inspired by the cycles of nature survived outside the main city temples until the end of the third millennium - that of the dying and resurrected chthonic snake gods. "Note: One must contrast the mode of Mesopotamian religion that was basically 'holistic' and closely reflecting or explaining the mysteries of nature, with that the post anthropomorphic, authoritative mode of religion that closely mirrored the rise of political hegemony in Sumer - and is embodied in Enlil in Nippur and later Marduk in Babylon. Also, we may wonder (until reviewing Wiggermann's chief work, directly) if earlier description of Ningishzida as a being venerated in a 'rural sanctuary' may directly correspond with the author comment "survived outside of the mail city temples." Pg. 1867: On the Prehistoric stage: The author comments here on the a stage of theology before writing, thus prehistory - or Mesopotamian theological ideas older than approx. 2500 B.C. Interesting comments read: " The later development of Mesopotamian theology implies an original pantheon of gods of nature, the most important being Moon, Sun and Venus;[and] their abode, Heaven; Earth; Ether, the space between Heaven and Earth; the hills and surrounding lowlands; and a number of chthonic gods associated with growth and snakes. Such gods had no gender (Sumerian does not formally distinguish between masculine and feminine nouns) and consequently no spouses or children. In the historical Sumerian pantheon, only Sun(Utu) and Heaven (An) retained their original names. The other original names were replaced with epithets: Moon was "Heavenly Lord"(Nanna); Venus was "Lady of Heaven" (Inanna); Earth was "Lord of the Earth" (Enki); Ether was "Lord Ether" (Enlil); Hill was "Lady of the Hills" (Ninhursag); the chthonic gods were "Lord Healer" (Ninazu) and "Lord of the True Tree" (Ningishzida). "PG. 1869 Wiggermann deals next relations gods were typically seen as having, however, in so doing he says something quite fascinating. First, it should be explained that earlier, we learned (if we didnt know already) that in each city, the city god was seen as having a mortal spouse of sorts in the figure of the En priest or priestess (depending on the sex of the deity in question. I have highlighted the key part of this the following of Wiggermann's comments: "The city gods were anthropomorphic, and consequently either male or female. Their gender, was not in all ass definitely fixed, and gender changes still occurred in the historical period. In the course of the third millennium, the anthropomorphic deities were supplied with spouses, in most cases artificial or secondary figures, and a court. The addition of a divine spouse confused the deity's relation with his human partner (the EN) and resulted in the curiously mortal god Dumuzi, Inana's husband in the historical period. At the end of the third millennium, his cult was associated with that of the dying and resurrected chthonic gods and that of dead rulers. " Note: Remember the Family tree of the Snake gods is given as: Ninazu > son of Ereskigal [variant tradition, of Enlil/Ninlil]> Ninazu is the Spouse of Ningirda (a daughter of Enki) Ningishzida> son of Ninazu/Ningirda > Ningishzida is the Spouse of Ninazimua* Damu> son of Ningishzida/Ninazimua Earlier, we had seen Jacobsen state that the cult of Ningishzida's son Damu was "influenced and in time blended with the very similar cult of Dumuzi the shepherd." ( see reply number 6 of this thread) But we had previously no word precisely on whether the tradition of Ningishzida or Dumuzid may have borrowed from each other , as they are both dieing gods who in myth make trips to the underworld (I.E. Ningishzida\s boat ride to hades.) With Wiggermann's comment that Dumuzi's "cult was associated with that of the dying and resurrected chthonic gods" at the end of the Third Millennium (maybe 2100 or so), he is saying here that the cult of Dumuzi here borrowed from the old tradition of (most likely) the Ningishzida or Ninazu cult and myth (even as the cult of Damu, Ningishzida's son, latr borrowed from that of Dumuzi.) What indeed might we learn from the man who wrote the article on the matter - or from the actual article itself? |

|

david

dubĝal (scribes assistent)

Posts: 43

|

Post by david on May 8, 2008 16:24:49 GMT -5

This one is done:  That is a very cool picture you've done, and it keeps putting me to shame (when I finish my essays for uni, I want to try and paint and create some pictures of Ereshkigal, hopefully, I can get them good enough to post up here). BTW, did you hand paint that or did you do it on computer?, either way, it definitely looks amazing and very cool (you are very talented, and could probably make a living out of it). |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on May 18, 2008 7:54:19 GMT -5

Hello Ningishziddians, While surfing through the Oriental Institute site I found a pdf file about excavations at a place called Choga Mish. Curious as I am, I looked through it and found some very interesting images which I'd like to share. Here are some links: oi.uchicago.edu/research/pubs/catalog/oip/oip101.htmlIf you download the OIP101 pdf (second arrow) you can see on page 61 an image of some clayshards, these contain the image in question which in turn is from a Vessal from the protoliterate period (object C). At page 235-239 you can see line drawings of the object. The most interesting drawing is on page 238 where we see entwined serpents, flanked by two panthers. Here you see an image quite similar in theme to the Gudea cup (refer to reply 6 of this thread for a visual.) However, this one is way older i think. "The archaeological site of Chogha Mish is located in the Khuzistan Province of Iran (Susiana Plain). It was occupied first beginning about 6800 BC and continuously from the Neolithic up to the Proto-Literate period." "Chogha Mish was a regional center during the late Uruk period of Mesopotamia; and is important today for information about the development of writing. At Chogha Mish, evidence begins with an accounting system using clay tokens, over time changing to clay tablets with marks, finally to cuneiform writing system. "Us4-he2-gal2: Further, this city was located near Susa, a city that changed hands between the Sumerians and Elamites early on. Susa was on the border between Mesopotamian and the lands to the east, and it was for Susa that the Susiana Plain was named. In many respects the Susania was an extension of lowland Mesopotamia." Excavations were conducted at the site in the mid-twentieth century by the Oriental Institute, under the direction of Pierre Delougaz and Helene Kantor." +++++++++++++++ Naomi, your art is very nice. Can't wait to add it to the enenuru gallery section. Cheers |

|

|

|

Post by ninanki on May 18, 2008 18:20:26 GMT -5

Hi, Michele here, new to the group. The dragon on Ishtar's gate is Marduk, not Ningishzidda. And the bull is Anu. Here's something I havn't been able to verify. The Ishtar Gate dragons are supposedly associated with Ningishzidda according to many websites out there, and a few books, but I can't seem to discover why this is? Is there an inscription or a plaque I'm missing? Or are they indeed the animal portrayed on the Lagash cup? I did a modern revamp of the Mûš-ruššû here:  And the original!  |

|

|

|

Post by ninanki on May 18, 2008 18:24:35 GMT -5

Ningishzida is male, and yes, his name means Lord of the Good Tree. I recommend "Netherworld" by Dina Katz. Lots of great stuff on underworld deities, lots of stuff of Ningishzida. Whoever wrote that about him being wife and mother is wrong. Although there was a point where the prefix NIN meant lady, it was originally a genderless honorific. The Sumerian language didn't genderize their pronouns and suffixes, so if you see something with a gender, such as en or -tu, you can guarantee that it is of semitic origin. Probably Assyerian or Babylonian. Per a professor at Oxford via Etana. Hello friends, I have a question and I assumed you could answer it for me. I am on another board discussing Ningishzidda and having read just about anything I was able to get my hands on I thought I had a good grasp of the basics, but then someone wrote this: "Ningishzidda, or Ng was the wife and mother of Dumuzi, and an ancestor of Gilgamesh. The whole family tree is very complicated with several names for each individual, which just adds to the confusion. To simplify Ng can be viewed as the serpent-god of Mesopotamia and also as the mother goddess/goddess of the earth/underworld. Ng could be viewed as an earlier version of Isis."My understanding was that Ningishzidda was a male deity, husband to Ninazua (Lady productive branch) and his name meant "Lord of the Good Tree" In your (scholarly) opinion, is the above paragraph in quotes true or not true? Here is a picture of Ningishzidda's symbol in a contemporary style I am working on:  |

|

|

|

Post by ninanki on May 24, 2008 1:18:05 GMT -5

Mmmm.... not sure where you got that from, but I would tend not to trust it. Ningishzida is always pictured with two serpents at his shoulders, not in dragon form. Not to argue with you, I'm sure you did see that example; it doesn't fit in with my studies, though, so I wouldn't agree with the author of that book. If we look at the images of the gods, they are almost always pictured with an animal. Now consider what Jabconson has to say in Treasures of Darkness, that "informed Mesopotamian religion with its basic character: the worship of forces in nature", and then on the progression of religion and society, "An early phase representative of the 4th millennium BC, and centuring on worship of power in natural and other phenomena essential for economic survival." which we then progress to these figures of nature in a more human form, we can deduce that the animal figures are the totemic, early images of that deity. Since the dragon belonged, originally, to Nammu, the Sumerian version of Babylonian Tiamat, it stands to reason that the image (and in essence her power) was passed from Tiamat to Marduk which he would have taken after he destroyed her. Although dragon and snake belong to the same animal family, they are two different creatures. It makes more sense to keep Ningishzida with his snakes, than it would be to place him with a dragon. Snakes have always held the meaning of renewal, which fits in with Ningishzida's role as the numinos energy of the tree (and life, if you want to bring in theory along with the Huluppu Tree myth). Dragon is primeval power, snakes are renewal. Michele Hi Michele My understanding from reading but not taking notes in a variety of local library books that the dragon was Ningishzidda, even on the Ishtar gate, but it was seen as a "tribute" animal to Marduk, ie it indicated Marduk's domination over the animals who were symbols of other gods, and the dragon was not Marduk himself, only a vehicle. There is a picture of Marduk standing on these dragons as if they were waterskis or something, somewhere. I would have to visit the library to discover this image again and right now I really don't have time. [glow=red,2,300]Sheshki, WOW WOW WOW OMG!!!!! I don't know what to say!!! That's just incredible what you found!!!!  [/glow] I'm so happy! Here is some faboo information us4-he2-gal2 posted on abrahadabra.com (where I am banned, unfortunately): I have a number of Mesopotamia art suggestions that have to do with visions no one has ever seen to pass on to you (zaqiqu/spi. summoning) Naomi, if I should you down a little longer next time.

Oh - I have a book here that says something on Mûš-ruššû (in this work the same name is rendered Muš-huššu and as this probably a more recent reading I will use it below.) The book in question is called "Civilizations of the Ancient Near East" and is actually part of a 4 volume series. The relevent article contained therein is called "Ancient Mesopotamian Religious Iconography" by A. Green. Green also produced a book which has become staple of ANE studies called "God's, Demons, and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia" in conjunction with Jeremy Black - Who I think you're already aquainted with.

Green first comments: "Perhaps the most striking thing in ancient Mesopotamian religious art is was the symbol. Generally, its significance was simple and direct. Certain relativly uncomplicated images - such as phenomena in the sky, tools of the land, animals, animal hybrids or animal-headed and other standards- were used as direct substitues for individual gods and goddesses. Occasionally a single deity might have more than one such symbol or a particular symbol might in exceptional circumstances stand for more than one deity or as a general attribute of any one deity. Generally, however, there is a one-to-one, often straightforward relationship between the image and the god or goddess thereby represented."

I myself don't have a good familiarity with the Muš-huššu as although known textually from early sources (loosely), scholarly sources give its first physical attestation as the Kassite period (1500 BC) and last attestation in the Seleucid period (305 BC). This is later in Mespotamian history then I usually focus. However, from Green, we get the description of the Muš-huššu as a '(snake-)dragon, with lion's forlegs and bird's hindlegs".

Some god symbols, Green says, are easy enough to understand and interpret - Utu the sun god is symbolised by a sun disk, Nanna the moon god by a crescent moon, Inanna a star (the planet Venus). Some were less clear. Some were plan complicated.. And, you have asked about the very example Green using to illustrate how it sometimes got complicated with god images! His explaination is as follows:

"An excellent example of how a symbol might be transferred between gods in the wake of theological and political developments is provided by the dragon called [Muš-huššu] (Furious Snake) in Akkadian (No.30). The complex mythologies and associaitons of various gods that involved the creature have been collected and explained by F.A.M Wiggermann. The origin of the dragon was apparently as as the beast of the underworld snake god Ninazu, who in the Third millennium BCE [2900 down] was worshiped in the city Eshnunna (Eshnunnak, modern Tell Asmar). When, in the Akkadian [2400] or early in the early Old Babylonian [1900] period, Ninazu was replaced as city god by Tishpak (probably in origin the Hurrian storm-god Teshubb), the latter took over the [Muš-huššu] his animal, which in Lagash (modern Tell al-Hiba) the beast became associated with Ninazu's son, the underworld god Ningishzida."

To sum - The monster was originally

a) Ninazu's creature in Eshnunna in the early period

b) Taken by Tishpak and Ningishzida in Lagash in the Akkadian or Old Babylonian periods

Green contnues: "From Middle Babylonian times [1500] , however, possibly after Hammurabi's conquest of Eshnunna, the dragon was transferred to the new Babylonian national god, Marduk , and to his son, Nabu. The Assyrian king Sennacherib destroyed Babylon in 689 BCE. Thereafter, the Muš-huššu is found in Assyrian art, usually the symbol of the national god Assur, whose cult assimilated much of the mythology and festivals associated with Marduk. On Sennacherib's rock reliefs at Maltai, the creature is seen as the mount of two deities, Assur and another god, probably Nabu. Although the "meaning" of the Muš-huššu dragon changed therefore, in terms of the specific deity or deities it represented, it remained fairly constant in terms of the types of gods it symbolized. Its distinctive reptilian iconography originated from its associations with the underworld and with an underworld god. By virtue of this god being the main deity of a particular city-state, the beast came to symbolize a succession of chief loal and national deities and their sons.

so we have:

c) Transferred to Marduk and Nabu in Middle Babylonian times

d) To Assur in the Neo-Assyrian period (at 689 BC)

P.S. Oh, and Green mentioned the work of F.A.M Wiggermann when he said " The complex mythologies and associations of various gods that involved the creature have been collected and explained by F.A.M Wiggermann." I have recently gained a few glimpse's into Wiggermann's work which I will post shortly at Enenuru, though I don't yet have the work itself, which is called "Transtigridian Snake Gods" and which is contained in a book which itself is called "Sumerian Gods and their Representations"

www.eisenbrauns.com/ECOM/_2D206TLSP.HTM

Transtigiridian refers to the Tigris river and Wiggermann must connect this with the cities of the Snake gods in some way. In anycase although the book is the essential for Ninazu, Ningishzida and related religion I would say, it must also error and limititation even still - while being the best in the field. Although it appears out of print at Eisenbrauns there are likely other places to obtain it, and as well I know someone who has it if he could be persuaded to review for us.. hm. |

I'm sorry my art was down i am reformatting my web images for my new portfolio so wait a couple of hours I shall have them up once more. |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on May 24, 2008 10:49:15 GMT -5

Ninanki:

The information Naomi has quoted is a blurb I wrote up a few weeks ago. As mentioned in that blurb this information is directly extracted from an article by Anthony Green, published in the "Civilization of the Ancient Near East" st - a huge 4 volume series which collects the all very best of the field into one series. Green is also responcible for the iconographic insights in the well known book we refer to as Black and Green (Gods, Demons and Symbols of the Ancient Near East), so you can believe what he has to say here about Mus hussu is authoritiative.

I believe what he is saying is not so much Ningishzida was not associatied with snake - rather he traces the symbol of hte Snake dragon (Mus hussu) to the early 3rd millennium, and to the local of Ninazu. Yes the symbol came ot Marduk, but only throgh the process described in the article.

|

|

|

|

Post by xuchilpaba on May 27, 2008 16:16:35 GMT -5

I love this picture! I like it alot better than the other one..

|

|

|

|

Post by ninanki on May 29, 2008 14:52:03 GMT -5

Not dragons on his shoulders, snakes. I have two pics of him here: www.babylon-rising.com/ningishzida.htmlOk, if you're talking about that author, I'll consider it. Still doesn't make sense, though, and even the experts have been known to be wrong. Information where I found the entry is in my post, please feel free to read it again if it was unclear. I am not sure either if the Muš-huššu is Ningishzidda's, perhaps us-he-gal can help explain. The first I heard of this was on Abrahadabra but I could not find any references to it, although it is not that hard to associate with the dragon cats on the cup, since they too, are horned, scaled, with bird feet and a wavy tail. If the ones on the Ishtar gate have scorpion stingers as wel, I cannot tell. What do you mean, when you say you see Ningishzidda, he is always depicted with dragons rising from his shoulders? What about the Lagash cup with the dragon cats/gryphons with scorpion tails? And you speak as i f there is more than one instance of Ning in human form, what is the other one? I know the one from Lagash of Ningishzidda leading Gudea towards water and that's it. unrelated to this tangent, I just happened to find this: Black and Green on Ningishzida as the star constellation, Hydra: "The symbol and beast of Ningishzida was the horned snake or dragon basmu (see Snakes) and astrologically Ningishzida was associated with the constellation we know as Hydra...See Damu; Snake-dragon; Snake gods." (p. 140. "Ningishzida." Jeremy Black & Anthony Green. Gods , Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, An Illustrated Dictionary. Austin, Texas. University of Texas Press. Published in co-operation with the British Museum Press, London. 1992) |

|

|

|

Post by ninanki on May 29, 2008 14:59:07 GMT -5

Off the subject but I just remembered.... Graham Cunningham! That's who I emailed for information on a few basic questions!! Knew I'd remember, if I saw the name. It's been a few years.

He told me that the Sumerians didn't genderize their words, like the Semitic languages do. If you see -tu at the end of a word, it probably has a Babylonian or Assyerian connection because -tu is feminine.

He also told me that Inanna's original name was probably Ninana, since the In prefix is Assyerian. Inanna really doesn't translate into Lady of Heaven. Ninana, however, does. Makes sense.

I got something else from him..... I'll think about it. My email binder is packed somewhere in the shed.

|

|

|

|

Post by ninanki on May 30, 2008 9:27:27 GMT -5

They're calling it a dragon? Ok. Too late for me to go knocking at their door to argue about it. Thanks for posting the other pics, those are great. I think I need to look into getting that art book. Could you post the author and ISBN #?

The conned hats represent deity. Haven't figured out how they understood the ribbed conned hats to mean deity, but that's what Kramer says.

Are you really confused over the names? If it helps, the prefix 'nin' is an honorific which means lord or lady. It used to mean just 'lady' but during language shifts it became nonspecific to gender. Giru, or girsu, means fire, or a type of fire. Urta refers to growing things, so is an earth reference. Ninurta used to be a fertility god of the fields before he became a storm god. Azu is craftsman, although if you shift the z to more of an s, it becomes disease.

The names are honorifics and epithets, rather than actual names.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on May 30, 2008 12:50:34 GMT -5

The Mus hussu did definitely come to have direct associations with Ningishzida in the complex manner outlined above. In regards to the snakes at Ningishzida's back, we can turn again to A. Greens article found in CANE vol. 3, specifically pg. 1844 ("green8.jpg.") Near the bottom Green states: "Another underworld god was Ningishzida. As he was the personal deity of Gudea, ruler of Lagash, he is depicted in the art of that time- for example, on Gudea's own cylinder seal, where the god introduces the ruler to the water-god Enki. Ningishzida is represented with horned Bashmu snakes (the horned viper Cerastes cerastes) rising from his shoulders (see fig.5 no. 4). " When we refer to "fig.5 no.4" , which is on pg. 1848 (green14.jpg), we see that no.4 is a little drawing of a horned snake. The accompanying information tells us, that this image is attested from the Akkadian (?) period, down to the Kassite period. It's proposed identity, its names in semitic language, are 1. bašmu and 2. ušumgallu and the proposed translation for both is "poisonous snake." Referring next to my favorite of all published books, G. Cunninghams "Deliver me from evil: Mesopotamian Incantations 2500-1500 B.C", pg. 78, There is a good comment on snake iconography, and some perspective as to its relation to the netherworld.

Cunningham: "Ninazu - whose name (Lord Physician) suggests an involvement with healing - is a chthonic god associated with the underworld. Thus one tradition refers to him the "šita of the underworld, given birth by Ereškigal; ('šita-ki-gal-la dereš-ki-gal-la-ke 4 tu-dal') 7. Snakes are also associated with the underworld: for example, one royal inscription requests the underworld goddess Ninki to punish a transgressor by sending 'a snake from the underworld' (muš ki-ta) 8. The Chthonic god has associations with the chthonic animal: for example, on $ulgi hymn relates Ninazu, in a broken content, to 'the fearsome snake' (muš-ḫuš) 9 and another describes him as 'born on the kurmušša (possibly snake mountain)' ('kur-muš-ša tu-da-a') 10. The deity is therefore appropriately invoked in Text 58 which is directed against the mythical ušumgal snake. This incantation confirms Ninazu's association with snakes given that its speaker addresses the ušumgal: 'Snake your king has sent me to you, your king Ninazu has sent me to you you' ('muš lugal-zu mu-ši-gi 4 lugal-zu dnin-a-zu mu-ši-gi 4'). 117. Sargonic Hymn Cycle 182 8. Pre-Sargonic Inscriptions E'annatum 1 rev v 36 9. $ulgi Hymn D 308. 10. $ulgi Hymn X 93. 11. Text 58 5-7 . For Ninazu see further Wiggermann 1992 pp.151-52 The incantation Cunningham refers to above incidentally we have obtained and listed on the Ur III Incarnations thread , reply #9. The translations itself reads: [C] 5. Snake, your king has sent me to you, *1 [C] 6. your king Ninazu [C] 7. has sent me to you. [C] 8. I have tied your nose with a cord! [C] 9. I have tied your tongue with string. [C] 10. Wild goat, I have tied you at the nose (and) tongue with taut cord. [V] 11. Do not attack the one that struggles, *2 [V] 12. the body (? uzu = known?) of [.... ] [V] 13. do not break. [V] 14. Against the man who struggles hide no poison. [C] 15. Ušumgal, your venom I have dried. *3 [C] 16. May the incantation formula, *4 [C] 17. the incantation of Eridu, the secrets, the mighty speech in the abzu, [C] 18. not be undone.

So far we see that Ninazu as a Netherworld god had associations with snakes - in particular he is related to the muš-ḫuš and has command over ušumgal in an incantation. We are not yet talking about the snakes on Ningishzida's shoulders, which we know (from the above) go by different names. The muš-ḫuš is what is called a chaos monster. Chaos MonstersBeginning in the Ur III period, incantations began to be directed not only against daimons (as in earlier periods) but also against chaos monsters. The beings were often a composite of different animal forms, and unlike daimons, only caused harm - they embody disorder as well as cause it. " Therefore the muš-ḫuš associated with Ninazu is a chaos-monster, which in some periods is treated like a daimon, is a bringer of sickness and disorder, and is targeted in incantations. Cunningham tells us that Snakes can be regarded as similar to chaos-monsters, given that in Mesopotamian terms they are classified with the same conceptual continuum as chaos-monsters of the serpent-type such as the ušumgal. Chaos Monsters and the Defeated Opponents ListCunningham further explains that the Chaos Monsters are similar to creatures mentioned in the list of defeated divine opponents. That is, certain myths include lists of creatures that gods have defeated. As it is we only have lists that Ningirsu/Ninurta and Marduk have defeated.. The defeated creatures after being defeated are subjected to the gods who defeated them or perhaps to the gods in general. Perhaps also gods who are associated with certain snakes or creatures have defeated their associated creatures in some lost myth cycle. Jacobsen, Black and Wiggermann have each offered interpretations and it is generally accepted that the defeated opponents are either a) non-human forms of anthropomorphic deities or b) minor local deities or c) concrete manifestations of aspects of anthropomorphic deities. I have quoted 2 of these listed of defeated opponents below, this first is beings Ninurta defeated as seen in Ninurta's Return. The second are beings Marduk defeated as seen in the Enuma Elish.

Ninurta's Return

Venomous snake (ušum)

seven-headed dog (ur-sag-imin)

six-headed wild ram (šeg-sag-aš)

captured cow (áb-dab5)

captured wild bull (am-dab5)

Enuma Elish

venomous snake (bašmu)

great venomous snake (ušumgallu)

giant snake (mušmaḫḫu)

fearsome snake (mušḫuššu)

wild dog (uridimmu)

To digest this information, we see that the very same snakes that feature on the Ningishzida's shoulder, the bašmu or ušumgallu, feature in a list of opponents defeated by Marduk (from the Enuma Elish). This does not mean that Marduk gave Ningishzida his symbolic associations or any such thing; Marduk's list of defeated opponents again borrows or adapts earlier traditions, however his list is the only extent list which lists these particular snakes as defeated opponents. It may suggest that these particular snakes were originally seen as divine opponents, akin to chaos-monsters, that they were originally symbols of disorder whose defeat and subjection to the god symbolizes divine power and efficacy in subduing destructive forces. It is possible they were in some early myth sequence (lost now) defeated by a snake god and subsequently they became " c) concrete manifestations of aspects of anthropomorphic deities," later to be included in Marduk lists of defeated gods, as Marduk absorbs earlier traditions. A good discussion of this would probably need to await Wiggermann.. Oh Madness??

Note: In the above Green has stated "Ningishzida is represented with horned Bashmu snaked (the horned viper Cerastes cerastes) rising from his shoulders ". In effect he is proposing an identification between a mythical creature and a scientifically categorized species. Even a highly mythologised creature takes its inspiration from something, and after browsing the wiki on Cerastes cerastes, I believe his suggestion is good despite the fact this snake isn't listed as inhabiting Iraq currently.

|

|

|

|

Post by ninanki on Jun 1, 2008 21:19:40 GMT -5

This is all interesting. I have a really bad memory, due to 27 years of migraines, so I tend to remember concepts and rarely actual quotes. I'm going to re-read Netherworld; lots of info on Ningishzida in it. Ok, I can see serpent or dragon, if we use the horned-viper. To me, though, a dragon has legs. Possibly the OCD at work.....

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jun 4, 2008 21:16:06 GMT -5

Ninantu: -We have had a discussion on the the "nin" prefix which Naomi intiated some time back and which became quite extended, see Gizzida and Ningishzida names - Don't worry about remembering quotes, who really has the mind for this? Researchers however, do very well to reference the relevant book and read the needed material. Saves brain capacity and increases accuracy in one motion ;] Naomi: - As for your earlier question on the hats which appear on divine inconography they definitly are not all that visuall appealing. I believe they are not ribs but horns. I have a discussion about headgear on my facebook group that maybe can carry over onto a new thread. - About the comparison to a panther in your above quote, we should explore how literally to take such compairsons or how much to read into this. Im just not sure yet. But Kramer wrote a piece on Sumerian similie, which we should consider. cheers

|

|

|

|

Post by madness on Jun 23, 2008 3:33:53 GMT -5

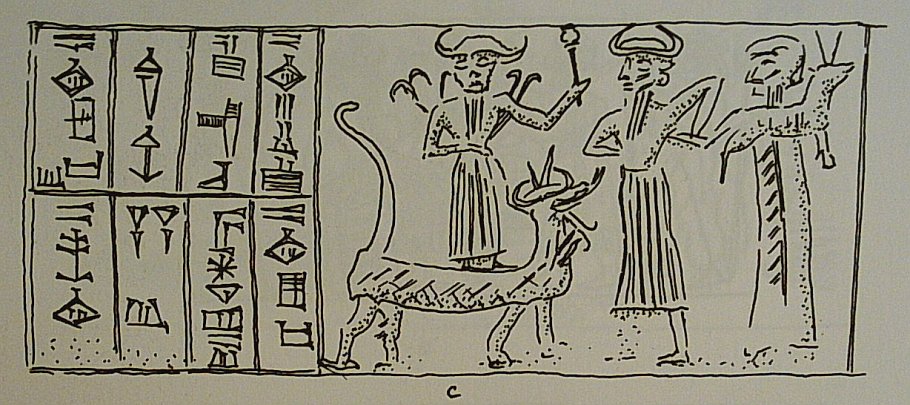

A look at F.A.M. Wiggermann's Transtigridian Snake Godsin I.L. Finkel and M.J. Geller (eds.), Sumerian Gods and their Representations. Cuneiform Monographs 7. FiguresFigure 1a - The constellation Hydra ( dMUŠ/ Bašmu) from a Seleucid clay tablet. Figure 2a - Boehmer UAVA IV abb. 283; ED III cylinder seal. Figure 2b - H. Frankfort, OIP 60 no. 331; Akkadian stone relief from Tell Asmar. Figure 2c - Boehmer UAVA IV no. abb. 570; Akkadian cylinder seal. Figure 2d - Historical development of snake-dragon/ mušhuššu (after Wiggermann, s.v. mušhuššu in RlA): 1) Protoliterate, 2) ED III, 3) Earlier Akkadian forerunner (snake's head); 4-6) Classical form and variants; 5) Winged snake-dragon of Ningišzida (from the seal of Gudea); 6) Variant Neo-Babylonian snake dragon of Marduk with feathered tail. For easier comparison all dragons are shown facing to the left. Figure 3d - Frankfort, Stratified Cylinder Seals Fig. 654 (= Boehmer UAVA IV Abb. 714); Akkadian cylinder seal from Tell Asmar. Figure 4b - H. Pittman, Ancient Art in Miniature (1987), 23 Fig. 11; Akkadian cylinder seal. Figure 4d - D. Collon, Western Asiatic Seals in the British Museum. Cylinder Seals II (1982), no. 186 (= Boehmer UAVA IV 580); Akkadian cylinder seal. Figure 5a - Upper part of stele of Untaš-Napiriša (13th century) from Susa; after P. de Miroschedji, Iranica Antiqua XVI (1981) Pl VII.

Ešnunna, the city of Ninazu/Tišpak Der, the city of Ištaran Susa, the city of Inšušinak These three transtigridian cult centres are located across the Tigris near the Iranian mountains. See wikipedia map: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Meso2mil.JPGThe canonical god list An-Anum treats the deities of death in tablet V: Ereškigal (V 213) Ninazu of Enegi and Ešnunna (V 239) Ningišzida (V 250) Tišpak (V 273) Inšušinak (V 286) Ištaran (V 287) It is this group of underworld deities that Wiggermann discusses (and two more: Ninmada, a snake charmer deity who is the brother of Ninazu; and a snake-like boat-god). This group of deities, being connected to trees, vegetation, snakes, and dragons, is distinct from the underworld war gods Erra, Nergal, Lugal-irra, and Meslamta-ea. Snakes and DragonsIn late astrological texts both Ereškigal and Ningišzida are associated with the constellation Hydra ( mul dMUŠ). To the Babylonians, this constellation appeared as "a snake drawn out long, with the forepaws of a lion, no hind-legs, with wings, and with a head comparable to that of the mušhuššu dragon (Fig. 1a)." The mušhuššu was the dragon of Ninazu, city god of Enegi and Ešnunna, and of his son Ningišzida. From Old Akkadian times onwards, Ninazu was succeeded in Ešnunna by Tišpak, whose traits mainly derive from Ninazu, including the association with mušhuššu. It is from Tišpak that the mušhuššu was taken, and given to Marduk, after the defeat of Ešnunna by Hammurabi. See fig. 2d for the development of the snake-dragon and refer to RlA 8 (1995), 455-462, s.v. mušhuššu. The earlier form was a lion with a snake's tail, as on the Early Dynastic seal in fig. 2a. Wiggermann states that this is indeed the mušhuššu as he compares it to a contemporary seal (Moortgat, VAR 147) showing a caged god and a similar dragon having an extremely long neck and a snake's head, and with a god, holding a mace in each hand, standing on the dragon. In fig. 2a the two three-headed maces are "forerunners of the later double-headed lion mace held by the god on the mušhuššu and by a number of other deities." A more developed form appears on an Akkadian alabaster relief group from a private house in Ešnunna, in fig. 2b. The dragon is now scaled and has the head of a snake, but is missing the horns and the hind-legs are not yet those of a bird of prey. The god standing on the dragon, either Ninazu or Tišpak, is also scaled, and is not yet completely anthropomorphic. "Since the piece was found in a private house, it probably played a part in the cult of dead ancestors, the typical house cult [Conceivably a domestic version of the important role played by Ninazu in rituals for the royal dead]." A fully developed form, in fig. 2c, appears on an Akkadian seal dedicated to the god I-ba-um. This I-ba-um "is probably identical with dIp-pu, the vizier of Ningišzida in An-Anum V 262. Here he is apparently the vizier of Ninazu, who introduces a visitor to his master." I-ba-um can be translated as "Viper." Although the god "Viper" of the seal is completely anthropomorphic, his master retains the ophidian nature of his vizier in the vipers rising from his shoulders. It is, in fact, not uncommon that the vizier embodies one of the properties of his master. Transtigridian Snake Gods, p. 37 Evidently the importance of the association of snakes with chthonic gods was forgotten about, as Wiggermann discusses: During the first half of the second millennium Mesopotamia loses interest in the snake-gods. Ninazu and Ningišzida, whose cult is not supported by important cities and was apparently in part a rural affair, show definite lack of character when their cults are combined with that of Dumuzi, a dying god of different origin. After that they disappear, at least as chthonic snake gods. The mušhuššu, Tišpak's dragon, loses all contact with his chthonic roots when after the defeat of Ešnunna he falls into the hands of the victor, Marduk, a god that is in no way chthonic. Transtigridian Snake Gods, p. 48 Ophidian OriginThe cult centre of Ninazu in southern Sumer, Enegi, was not much more than a village, compared to Ešnunna which was an important city. His ophidian traits at Enegi only gain importance in the late third millennium, and in the early second millennium the ophidian lore spreading from his temple in Enegi "is written mostly in foreign languages and appears to have been imported." Gišbanda "Young Tree" another name of Ningišzida "Lord of the True Tree" and also the name of his cult centre between Ur and Lagaš in southern Sumer, was a rural setting and not a city or town. The iconography of Ningišzida in Lagaš was probably imported from Ešnunna. It can of course not be denied that Ninazu and Ningišzida are Sumerian gods, but the evidence suggests that their ophidian traits were developed under the influence of transtigridian religious ideas. In fact, as has been repeatedly shown, a religious interest in snakes in these regions goes back deep into prehistory and through the ages remains quite visible in the iconography of Elam and the Iranian mountains. Transtigridian Snake Gods, p. 48 Tišpak is Ninazu's successor, and is virtually identified with him, in Ešnunna. In iconography he is shown with a plough, such as on the seal from Ešnunna in fig. 3d. Also notice that the god's hand ends in a scorpion, a popular motif in the Early Dynastic period but one that had died out in the Akkad period. However another Akkadian example is seen in fig. 4b. Ištaran is the god of Der in the Elamite borderland. Although his three main traits are that of a dying god, an arbitrator and judge, and a chthonic snake god, he is also related with the sky: he is a Semitic Venus ( Ištar-ān) and one of his names is An-gal/ Anû rabû "Great An." He appears with an anthropomorphic torso but with the lower body of a winding snake, as in figs. 4b and 4d. Inšušinak "Lord of Susa" happens to be a Sumerian god on Elamite territory, probably introduced in Susa by the Sumerian colony there in the Late Uruk period. Fig. 5a, a stele dedicated to Inšušinak, shows the god holding the rod and ring in his right hand, seated on a throne of a winding dragon, and holding in his left hand a second dragon branching off from the throne. Fire altars can be seen before snake-gods, such as in fig. 4d: Once the chthonic character of these gods is recognized, a plausible solution for the presence of the fire altar lies at hand: the earth gods need it for warmth and light in their dark and damp environment. Transtigridian Snake Gods, p. 46 |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jun 24, 2008 1:03:04 GMT -5

Lovely posting Madness! This is fascinating - exceptional  We will need to digest this all in detail, compose earth.google tours of the transtigidian area, discuss these rare iconographic insights etc etc - and doesn't the first specimen in figure 2d remind you of Sheshki's art picture here (I see you have named this item 'mush-hush' Sheshki - how did you guess what it was?) To follow up with a break down and examination of the above post soon. Wonderful study!  |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jul 3, 2008 11:13:33 GMT -5

Reviewing the Transtigiridian post: Hey all - The above post may appear thick to some or difficult, and because this really represents in some ways the farthest that scholarship has gone with Ningishzida, it would be worth it to review or highlight some of the great parts. First of all. the word 'Transtigiridian' is extremely obtuse I'd almost speculate that Wiggermann made it up ;] What it means though is trans-tigris , that which passed over the Tigris river. In this case, the author has implied that the ideology of the snake gods crossed the Tigris from Iranian territories. Above Madness has reproduced an image that appears in Wiggermann's article. Fig. 2c:  In this image we have.. On left: Ninazu on the mus-hussu middle: His vizier I-ba-umon right: A guest As is explained this is in fact the impression from an Akkadian cylinder seal, dating most likely to somewhere around 2400 B.C. This is intriguing for a number of reasons; It is the earliest representation of Ninazu I've seen - as well, it is the first indication I've got of his vizier I-ba-um (whose name means viper.) The importance of this article is that it attempts to show the influences of the Iranian ideology on these certain Sumerian gods. To understand this, some idea of the geography is important - because Wiggermann has it that these ideas came from the Iranian plateau, and crossed the Tigris and from there were dispersed into Sumer itself. For now, we might refer to the little map Madness has thoughtfully linked: Wiki mapNote that in this map, Eshnunna is very northern and is also not far from the Iranian border. We can't see the border here, but the towns of DER and SUSA are also close to the Iranian border and so we can get a sense of the divide. In the above explanations pay close attention to the content under the heading Ophidian Origins. Taking a close look at the first sentence we see the comment: "The cult center of Ninazu in southern Sumer, Enegi, was not much more than a village, compared to Ešnunna which was an important city." Keep in mind that Ninazu has two important cult centers, one was Enegi in the south, the other was Ešnunna, which we have seen to be in the far North. near the Iranian border. What do we know of Enegi? Not much, it being a small center not much much more than a village - but it did feature in some mythology. A quick look as etcsl brings up these two pieces.. a) Nanna-Suens journey to Nibru [Nippur]In this narrative, the moon god, Nanna, departs on a journey by boat to Nippur to the north east and he plans to make offerings to Enlil there. Nanna's city is Ur in the far south, so our journey starts there; according to the myth, Nanna's boat makes several stops along the way. Whats interesting here, is that his first stop is in the Enegir [Enegi]! It is received by Ningirida who is Ninazu's spouse. (Enegir [Enegi] lay ahead of the offerings, Urim [Ur] lay behind them.) After the Boat departs Enegi heading to Nippur once again, it soon stops at another local, and this time it is Larsam [Larsa] (Larsam lay ahead of the offerings, Enegir lay behind them.) We can therefore say that Enegi was most likey a small locality between Ur and Larsa - checking the map again this is still in the extreme south of Sumer. b) Ninazu's cult center in the south, Enegi, appears to have been quite involved with the ideology of the netherworld, and it compared to a libation pipe - the pipe (sometimes made of reed) that would be inserted into the ground at a gravesite, in order for the dead to receive liquidized offerings. One of the Temple Hymns is explicit about this: O Enegir, great libation pipe, libation pipe to the underworld of Ereškigala, Gudua (Entrance to the nether world) of Sumer where mankind is gathered, E-gida (Long house), in the land your shadow has stretched over the princes of the land. Your prince, the seed of the great lord, the sacred one of the great underworld, given birth by Ereškigala, playing loudly on the zanaru instrument, sweet as the voice of a calf, Ninazu of the words of prayer, has erected a house in your precinct, O house Enegir, and taken his seat upon your dais.

7 lines: the house of Ninazu in Enegir.

So we see a little about Enegi - whats explained by Wiggermann is that this local, while it had Ninazu as its patron god from early times, only depicted this deity as a Snake god later on "toward the end of the third millennium" or somewhere between 2350-2000 B.C. lets say. We are to assume then at this time, Enegi accepted influence from Ninazu's northern cult center of Eshnunna, which had for some long time been depicting Ninazu as a Snake god - this in turn is likely due to influence from the Iranian plateau's not far away from Eshnunna. To repeat Wiggermann's important statement: "It can of course not be denied that Ninazu and Ningišzida are Sumerian gods, but the evidence suggests that their ophidian traits were developed under the influence of transtigridian religious ideas. In fact, as has been repeatedly shown, a religious interest in snakes in these regions goes back deep into prehistory and through the ages remains quite visible in the iconography of Elam and the Iranian mountains. "At this point it may be worth it to remind readers of this thread of the image that Sheshki came across - the below is a seal depiction featuring entwined serpents from Choga Mish. This city, Choga Mish, is located on the Susanian plains just inside the Iranian border and not far from Susa. The image itself is ancient, dating from before 2500 B.C. We see here something of what Wiggermann most likely refers to when he states the Iranian religious interest in snakes goes back to prehistory - that same religous interest which would cross the Tigris to Eshnunna, Susa and Der, and from there influence the Sumerian depiction of the Sumerian cthonic deities. More summations to follow..

|

|

|

|

Post by madness on Jul 3, 2008 21:37:52 GMT -5

In this image we have..

On left: Ningishzida on the mus-hussu

The god on the dragon is Ninazu.

|

|