|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 23, 2012 19:27:54 GMT -5

G

[{d}]|GA2xAN|#-AN-MUSZ3-KUR P225959

{d}|GA2xAN|#-ra P010103, P225961

{d#}|GA2xIGI@g|-LAK672# P010103

{d}|GA2xMUSZ#|(LAK696) P225924

{d}|GIR3xSZE| P020429

{d}|GUD+TI| P010103, P225964

{d#}ga2#-tum3-du# P010103

{d}ga2-tum3-du10 P010566, P220697, P220703,

{d}gab2-gul P010566

{d}gal-e2-nun P010566

{[d]}gal#?-ga P010566

{d}gal-ga-iriP010870

{d}gal#-ga-uru P222174

{d}gal-iri-ga P010570

{d}GAL-NI-LA-x P225958

{d}gal-UN P010566

{d}GAN2-he2-|GAM.GAM| P010566

{d}GAN2-nun P010566

{d}gan-gir2 P220704, P220848, P010103, P222614

{d}gan-tur3 P220697, P220703, P221730

{d}GAN-ZI# P225924, P225925

{d}gar3 P010103, P225959

{d}gaszam P221673, P221699

{d}ge6-tur3 P010566

{d}geme2-zi-da P011010

{d}gesz-bar-e3 P010566

{d}geszimmar#-x [(x)] P225925

{d}gesz-zi-da P020275

{d}GI P010566

{d}gi#:bil# P010103

{d}gi6-par4-si P010570

{d}gibil6# P222153, P010508, P010566, P010600 P010570

{d}gir2-su P225925, P010103

{d}gir2-AB# P010566

{d}gir2-tag# P010566

{d}giri3 P225925, P225931, P010103

{d}girinx-gin7-du10 P010700

{d}gu2-la2 P010485, P010103, P010570, P010566

{d}gu2-szu-du8 P431040

{d}gu4-a2-nun-gi4 P010566, P225961, P010103

{[d]}gu4?-a2-[nun?]-gi5 P010566

{d#}guda2-nun P225961

[{d}]gudu4-nun P010103

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 24, 2012 11:30:56 GMT -5

H

{d}|HIxNUN.ME.U| P010103

{d}|HIxNUN.ME|(|SUMASZ.ME|) P225924

{d}HA-ESZ2-LU P225925, P225931

{d}ha-ia3 P227582

{d}har-nun P010566

{d}HE2-ga-ma-DU P010566

{d}hendur-sag P010566, P221796, P220697, P220703, P220848

{d}HUB2-x P010566

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 24, 2012 18:57:00 GMT -5

I

{d}i7 P225854

[{d}]i7#-da P221578

{d}i7-mah P222183

{d}i7-sze3 P020573

[{d}]i7-zalag-ga P221608

[{d}]i7-zi P216094

{d}IB P011024

{d}ib-gal P010562

{d}idigna(|TUMxPAP|)!? P225924

{d}idim(LAK4) P010566

[{d}ig]-alim P221796, P220704, P220848, P010566

[{d}ig-alim-ma] P222604

{d}igi-ama-sze3 P220841, P220942

{d}IGI-KU P225958

{d}ilx(KISZ)-la P225925, P225931, P010103, P010566

{d}inanna P221796, P221673, P220697, P220703, P221730, P010103

{d}inanna eb-gal P220703, P220847, P221730

{d}inanna-kur-si P010566

{d}inanna-menx(|GA2xEN|)* P221716

{d}I-NUN P225924

{d}i-pi-ku P225958

{d}irhan P222183

{d}iri-gal-ga P010566

{d}iri?-za3-x P010566

{d}IR-MUSZ-HA-DIN-BALAG# P225958

{d}iszkur P010485, P221796, P220703, P221730, P010103, P221362, P010566

{d}isztaran# P010103, P010566, P011024

{d}izi P010566

{d}izi-dag P010566

{d}izi-gar-dim2 P222174, P010570

{d}izi-la2 P010566

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 24, 2012 19:36:18 GMT -5

K

{d}KA-DI ...]-x P010102

{d}KAK-IG# P225925

{d}KALAM#?-KI P010566

{d}KA#-nun#-ku3 P010566

{d}kas-gal{muszen} P010566

{d}kesz3 P225924

{d}KI#-BAN? P011112

{d}KID#? P225958

{d}kid-szu2-DU P010566

{d}kid-szu2-tur3 P010566

{d}ki-du3-sumasz!(LAK225)-mah2 P010566

{d}KI-IG#-SZU P225925

{d}ki-ki{muszen} P010103, P010566

{d}kinda2-zi# P010562

{d}kin-nir P010706

{d}kin-sze3-la2 P010570

{d}ki#-nun-si P010566

{d}KISAL-si P010569

{d}KISZ P225925, P225931

{d}kisz:din-sikil! P225958

{d}kisz{ki} P010103

{d#}KISZ#-am#-gal P010103, P225961

{d#}KISZ-AN P010103

{d#}KISZ-BUR2# P225958

{d}KISZ-ISZ P010103

{d}kisz-ki-gal P010102, P010562

{d}kisz-ur-sag P010102

[{d}]kisz#-x P010102

{d}KI-UD-ug5 P010566

[{d}ku3-{su3}]|PA.EL|# P225958, P225961, P010103

{d}ku3#-ad# P010103

{d}ku3-nun-KAL P010566

{d}ku3-PAD-lam P010566

{d}ku3-PA-EL#-su3#-ga P221376

{d}ku3-rib-ba P010566, P010103

{d}ku3-su3-PA-EL-ga P225755, P227557, P221709, P221699

{d}ku3-tuku? P010566

{d}ku3#-x-x-SAL-SAL P010566

{d}kur{ki}-ta-e3 P010870

{d}kur-e3(|UD#.DU|)# P225958

{d}kusz7-ba-U2 P010103

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 26, 2012 19:48:12 GMT -5

L

{d}{la}lazx P011024

{d}|LAGABxGAL| P221796

{d}LA P225959

{d}LAK175-ma-[(x)] P010566

{d}LAK242-[(x)] P010566

{d}LAK566 P010566

[{d}]LAK566(|DUGxKASKAL|)# P225959, P010566

{d}LAK765 P010870

{d}LAL2-MUSZ3? P010566

{d}lamma P221796, P220704, P220848, P222174, P010103, P431040, P010570

{d}lamma-igi-hul P010566

{d}lamma-iri P010562

{d}lamma-menx(|GA2xEN|) P010566

{d}lamma-sza6-ga P221796, P222604

{d}lamma-uru P010103

{d}lam-sag-za-gin3 P010566, P225958

{d}li9-si4 P220878, P225931, P010103

[{d}lu2?]-lil?-nu P010566

{d}lu5-ga P010566

{d}lugal P010562, P010566

{d}lugal#-[BU?-NUN?-GAN2?-x?] P225958

{d}lugal-{gesz}asalx(|TU.GABA#.LISZ#|) P010103

{d}lugal-|SAGxX| P225958

{d}lugal-|URUxUD| P222174

{d#}lugal#-a-ki# P225958

{d}lugal-ambar P010566

{d#}lugal-aratta(|LAM.RU|) P010103

{d}lugal-banda3{da} P010566, P010103, P225961

{d}lugal#-BU#-NUN#-GAN2#-x P010103

{d}lugal#-dar# P225958

{d}lugal-dur# P225958

{d}lugal-e2-musz3 P220848

{d}lugal-e-gur P010566

{d}lugal-elam P010103

{[d]}lugal#-gir2# P010566

{d#}lugal#-gi-zi P225958

[{d}]lugal#-IMIN-GI4# P225958

{d}lugal-ISZ-|EZENxAN#|(LAK613) P010103

{d}lugal-kalam#! P225959

{d}lugal-ku5-da P225958

{d}lugal#-masz-masz P225958

{d}lugal-mes-lam P010570, P010017, P225959

{[d]}lugal#-NE# P010566

{d}lugal-SAG@g-DU!(KU7) P010103

{[d]}lugal#-SAHAR P010566

{d}lugal#-SIG4 P225958

{d}lugal-sila P010566

{d}lugal-sud2 P010103

{d}lugal-SZA6 P225958, P225959

d}lugal#-U2-GU#-IGI@g# P225958

{d}lugal-UD P222174

{d}lugal-ur-tur3 P431040

{d}lugal-uru11 P222399

{d}lugal-uru11{ki} P220697, P220703, P221730, P222496

{d}lugal-uru2# P010570

{[d]}lugal#-x P010566

[{d}]lugal#-x-AB# P225958

{d}lugal-za3-e3 P225958

{d}lul-dul3-le P010566

{d}lul-lul P225958

{d}LUL-NI P225958

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 26, 2012 20:01:26 GMT -5

M

{d}|MUSZ3.USZ| P225854

{d}|MUSZ3xZA.ZA| P225851, P225870, P225871, P225872, P225874

{d}ma2-ti P010103, P225964

{d}masz2-x-zu-da?-kas4# P010566

{d}masz-masz-zi P010566

{[d]}ME P010566

{d}ME-DAR# P225958

{d}me-dim2-sza4 P010103

{d}ME-e2#-nun P010103

{d}ME-ESZ2 P010103, P225958

{d#}me-gar P225958

{d}me#?-[kul?]-aba4{ki}-ta P220868

{d}me-lam2 P010566, P010570

{d}me-nu-nus-DU P010566

{d}menx(|GA2xEN|) P010566

{d}ME-RU P225959

{d}mes P010566

{d#}ME-SAG-DU P225958

{d}mes-an-du P220848, P221730, P250388, P221699, P220697, P220763

{d}mes-E2-NUN-ta-e3 P010566

{d}mes-eden P010566

{d#}mes-kalam# P225958

{d}mes#-lam#:ta#-e3(|UD#.DU|)# P222174, P010103, P010566

{d}mes-sa-du-ka P221285

{d}mes-sanga-unu P010566

{d}mu-an P010566

{d}muhaldim-zi-unu P010566

{d}mu-nun-DU P010566

{d}munus-gesz-nu11#-[(x)] P010566

{d}munus-nun-pa4-su13-banszur P010566

{d}MUNUS-U8-zi P010566

{d}munus?-x-nu-x P010566

{d}MUSZ3# P010103

{d}MUSZ3-AN-MUSZ3#-KUR P225959

{[d]}MUSZ3#?-KUR-HE2 P010566

{d}musz#-ir-ha-TIN-[...] P010566

{d}musz-ir-ha-TIN-BALAG-UD P010566

{d}MU#-SZITA?-LAGAB#? P225924

{d}musz#-KU#?-KU#? P010566

{d}musz-pad!-da-DU P010566

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 27, 2012 10:03:54 GMT -5

Fasten your seat belts here comes...

...N

{d}{nu}NUNUZ P225925, P225931, P225958

{d}{nu}NUNUZ:HI P225925, P225931

{d}{nu}NUNUZ-|LAGABxGUD+GUD| P225958

{d}{nu}NUNUZ#-gal5 P225958

{d}{nu}NUNUZ-HI P225958

{d}{nu}NUNUZ-x P225958

{d}NAGAR# P010566

{d}nam-|URUxSIG4| P010772

{d}nam-|URUxSZESZ2| P010570

{d}nam2-abzu P010566

{d}]nam2#?-a?-[x-(x)] P010569

{d}nam2-gi#?-[(x)] P010566

{d}NAM2-KISZ# P010103

{d}nam2-me-gara2 P010566

{d}nam2-nir P010566

{d}nam2-nun P220821, P222174, P010569, P010570

{d#}nam2-urta P010103

{d}nam2-x P010566

{d}namma P010566

{d}NAMMU-LAK592 P010566

{d}nanibgalx(NAGA){gal} P010566

{d}nanna P010489, P010103

{d}nansze P221796, P220697, P220697, P220703, P221730, P222390

{d}na-ru2 P225925

{d}NE P010700

{d}ne3-urugal2 P225925, P225931, P010103

{d}NE#-dag# P225958

{d}nergalx(|KISZ.UNUG|) P010566

{d}NI2 P010085

{d}NI2-lu-lu P010566

{d}ni2-pa-e3P222604

{d}ni-dam-gi6 P225958

{d}nig2-SAR P010562

{d}NI-la2-x P010566

{d}nin P010982

{d}nin#-[DI-ug5] P010103

{d}nin#-[ti] P225964

{d}nin-{d}inanna-e2!-gal-sze3-ba?-DU P010566

{d}nin-{gesz}kiri6-KA P010566

{d}nin-{ka15}kas2-si# P225961, P010103, P225958

{d}nin-|EZEMxASZ|-e2-gal P010566

{d}nin-|GA2xMUSZ| P010566

{d}nin-|GESZxKID2|-a-x P020586

{d}nin-|HIxNUN| P010103, P225958

{d#}nin-|KAxME|-KID# P010103

{d}nin#-|LAGABxMUSZ| P010103

{d}nin-|MUSZ%MUSZ|-da-ru P221673, P221699, P220821, P227555, P221316

{d}nin-|MUSZ%MUSZ|-ru P010566, P0105700

{d}nin-|NINDA2xBULUG3| P010566

{d}nin-|NINDA2xHI|# P010566

{d}nin-a P010566

{d}nin]-a:zu5-x P010103

{d}nin-a2 P010566, P010103, P225958

{d#}nin#-AB-[...] P225958

{d}nin-AB-x P010566

{d}nin-a-di P010566

{d}nin-aga3-szum2 P010566

{d}nin-a-gub2 P010566

{d}nin-a-LAK590 P020586

{d}nin-alla P010566

{d}nin#-ama# P010103

{d}nin-AMA-ME P010566

{d}nin-a-mir P010566

[{d}]nin#-an P010103, P225958

{d}nin-<<AN>>-tin-ug5# P010566

{d}nin-apin P010103, P225961

{d}nin-asilal3(|A.EZEM|) P010566

{d}nin-a-su P220701, P220704

{d}nin-aszag P225961, P010103

{d}NINA-ta-e3 P010566

{d}nin-azu P010566

{d}nin#-BA?-nun P010566

{d}nin-BAR:LA-ASZ-ESZ2 P225961

{d}nin#-BAR#:LA#-ESZ2 P010103

{d}nin-bara2 P010566

{d}nin-bi2-lu#-lu P010566

{d}nin-bil-lu-lu P225958, P225959

{d}nin#-BU#-|SZA#xDISZ#|-NUN#-KI# P225958

{d}nin-bulug3 P010566, P225958, P010103

{d}nin#-BU-NUN-KI-x P225958

{d}nin-bur# P010566

[{d}]nin#-da/a2#? P010566

{d#}NINDA2#-gu4-gal# P225958

{d#}nin#-da-HI P225959

{d}nin-dam-an-kusz2 P010566

{d}nin-dam-ge6 P010566

{d}nin-dar P220697, P220703, P220786, P221730, P222496

{d}nin-DI P010566

{d}nin-DI-TI-RA#? P010566

[{d}]nin#-DI#-ug5(|EZENxAN|(LAK613))P225958

{d}nin-DU P010566, P225962

{d}nin-du6 P010566

{d}nin-dub P221796, P220697, P220703, P221730, P010566

{d}nin#-dumu#-sag#? P225959, P225958

[{d}nin]-DUR2-TUG2 P010566

{d}nin-e2 P010566

{d}[nin]-e2-duru5 P010566

{d}nin-e2-gal P010566

{d}nin-e2-gal-ZA7 P010570

{d}nin-e2-ku3 P010566

{d}nin#-e2-SUM#? P010566, P221801

{d}nin-e2-za7-gal P010870

{d}nin-edin P010566

{d}nin-eme5(|SAL+HUB2|)? P010103, P225961

{d}nin-en-te P010566

{d}nin-er2(|IGI.A|) P010566

[{d}]nin#-esz:kug P010103

{d}nin-esz3-dar P010103

{d}nin-esz3-LAK175 P431040

[{d}nin]-esztub{ku6#} P010566

{d}nin-ezem-esz3 P010566

{d}nin-gal P225925, P225931, P010103

{d}nin-gal-tur3 P225959, P225958

{d}nin-gesz-gi P225959, P010566, P225958

{d}nin-gesz-zi-da P225931, P010566

{d}nin-GI P010566

{d}nin-gi4#?-sila4? P010566

{d}nin-gi-ge6 P010566

{d}nin-gir2-su P221798, P221796, P221670, P220703, P220703, P221730, P010103

[{d}]nin-gir2-su-nibru{ki}-[ta-nir]-gal2 P221384

{d}nin-giri16? P010566

{d}nin-girimax(|A.HA.BU.DU|) P225925, P225931

{d}nin-girimx(|A.HA.MUSZ.DU|) P010566

{d}nin-girimx{|A.BU.HA.DU|} P221801, P221796,

{d}nin#-gu4-ga-[(x)]-DU# P010566

{d}nin-gu4-sag P010566

{d}nin-gublaga P221796, P221441, P010566

{d}nin-gukkal# P225958, P010103

{d}nin-gur7#-gur7# P225958

{d}nin-guru7 P010566, P221796

{[d]}nin-HI{ku6} P010566

{d}nin-hur-sag P010566, P220704, P222183

{d}nin#-hursag#!(|PA+DUN3#|) P010103

[{d}nin]-ib2? P010566

{d}nin-ILDAG#? P010566

{d}nin-ildu3 P010103, P270822, P010566, P225961

{d}nin-imma3 P010566

{d}nin#-in#? P010103

{d#}nin#-in#-gar# P225958

{d}nin-iri P010566, P220841

{d}nin-iri-sza3 P010570

{d}nin-isinx(IN) P010566

{d}nin-KA P010566

{d}nin-ka-asz-bar!-ki P010566

{d}nin-KA#-GISZ#? P010103

{d}nin-KAK-KASZ#-si P010566

{d#}nin-kar P010103

{d}nin-KA#?-SAR P010566

{d}nin-kas-bar P010870

{d}nin-ka-si P222174, P010570

{d}nin-kaskal P010566, P010570

{d}nin-ki P010103, P222399, P010566

{d}nin-ki#-gar P010103

{d}nin-KID P010103

{d}nin-ki-da P222174, P010570, P010700

{d}nin-ki-en-gi-sze3 P010566

{d}nin-ki-im-DU P010566

{d}nin-ki-ki#{muszen} P010566

{d}nin-kilim P010566, P222174, P010103, P010570, P010870

{d}nin-kilim{+gi4-li2} P010566

{d}nin-kilim-asz-bar P010570

{d}nin-kilim-sila4-dah P010566

{d}nin-kin-nir P010570

{d}nin-ki-nu2 P010566

{d}nin-ki-sa2 P010566

[{d}nin]-ki-SAL P010566

{d}nin-ki-[(x)]-ku3 P010566

{d}nin-ki#-za3# P010566

{d}nin-ki#-za-ak-si P010566

{d}nin-kur P010570, P010700

{d}nin-LAK358 P010566

{[d]}nin#-lam-DU P010566

{d}nin-lamma-e2-sag-sur P010566

{d}nin-lamma-gi6-edin P010566

{d}nin-lamma-gi-ug5 P010566

{d}nin-lamma-szeg12#-tu P010566

{d}nin#-lamma-zi P010566

{d}nin-lil2(KID) P010566

[{d}]nin#-lilx(KID) P222763

{d}nin-limmu2 P010103

{d}nin-LUL-TUK-GUD P225958

{d}nin-mah2 P010566

{d}nin-mar P010570

{d}nin-mar{ki} P221476, P221670, P247619, P221697, P221695, P221371

{d}nin#-mar-gi4 P225958

{d#}nin-mar#-gi4# P225959

{d}nin-masz P010566

{d}nin-me P010566

[{d}]nin#-me-[szu]-du7# P010021

{d}nin-me-nu-e3 P010566

{d}nin-menx(|GA2xEN|)-kal P010566

{d}nin-me-szu-du7! P010570, P010705, P010747

{d}nin-mete-gal-ti P010566

{d}nin-mu2 P315467, P221485, P220704, P220771, P220848

{d}nin#-musz#-[x] P010103

{d}nin-musz3-bar P220697, P220703, P221730, P222496

{d}nin-musz3-kur P010566

{d}nin-nagar-esz3 P010566

{d}nin-nam2#?-ki#?-DU P010566

{d}nin#-NI#? P010566

{d}nin-nigar P010566, P010570

{d}nin-nigar P010570

{d}nin-NU2 P010566

{d}]nin-nu-nir P221796, P220841

{d}nin-nun-kal P010566

{d}nin-PA P010501, P010524, P010570, P010705

{d}nin-PA-gal-ukken P010570

{d}nin-PA-men P010532

{[d]}nin-PESZ P010566

{d}nin-pirig P010566, P010570

{d}nin-ri8-ru P010979

[{d}nin]-rin4#-ru P225958

{d}nin-sa2:a P225924, P010103

{d}nin-sag3 P220847, P431040

{d}nin-SAR P010570, P010103 P010566

{d}nin-SAR#-sag# P010103

{d}nin-sa#-za(LAK798) P225959, P225958

{d}nin#-SIG4 P020586

{d}nin-su13-ag2 P010566

{d}nin-sud2 P010103

{d}nin-su-ga P010566

{d}[nin?-sun2?] P010103

{d}nin-sun2!-LAMMA P010566

{d}nin-sza3-iri P010870

{d}nin-[sza3?]-uru#? P222174

{d}nin#-szag5# P225958, P225959

{d}nin-szara P225958

{d}nin-szara2 P221241

{d}nin-szeg12-tu P010566

{d}nin-szeg5-szeg5 P010566

{d}nin-szen P010566

[{d}nin]-szesz2(LAK668) P010566

{d}nin-szilig P010566

{d}nin-szuba3 P010566

{d}nin-szubur P221476,P221673,P247619, P221697, P221699

[{d}nin]-szubur#-mah2 P010566

{d}nin-szu-du7 P011034

{d}nin-szu-gisal P010566

{d}nin-szuszinak(|MUSZ3.EREN|) P225961

{d}[nin]-szuszinak(|MUSZ3:SZESZ2|)P010103

[{d}nin]-szu-tur#?-sze3 P010566

{d}[nin-ti] P221672, P221336

{d}nin-ti-menx(|GA2xEN|) P221710

{d}nin-tin{ti}-ug5(|EZEMxAN|)-[ga] P010570

{d}nin-tin{ti}-ug5#-<ga> P010570

{d}nin-tin-ug5#-ga P010569

{d}nin-ti-[ug5-ga] P222174

{d}nin-tuP221798,P221797,P221796,P220703

{d}nin-tu zabala5{ki} P221798, P221797

{d}nin-UD P010566

{d}nin-UD-da-e3 P010566

{d}nin-UD-KA P010566

{d}nin-UL-a P010566

{d}nin-ul-du10 P010566

{d}nin-unu P010566, P010103

{d}nin-unug# P010532

{d}nin-ur3 P220697, P220703, P221730

{d}nin-ur4 P221796, P010103

{[d]}nin#-uri5 P010566

{d}nin-urta P222183, P010566

{d}nin-uru:sag P225961, P010103

{d}nin-uszur3# P010566

{d}nin-uszx(LAK777)-du6 P010566

{d}nin#-utua(LAK777)#-x P225958

{d}nin-utuwa(LAK777)-X P010103

{d}nin-x-a2#?-x P010566

{d}nin-x-ama-na P221730

{d}nin-x-PI P010566

{d}nin#-x-PIRIG#-TUR P225958

[{d}nin-x]-SAR P010566, P010566

[{d}nin]-x-sze3 P010566

{d}nin#-[(x)]-ti# P010566

[{d}]nin#?-x-x-LUL# P225931

{d}nin-za3 P010566

{d}nin-zadim P220770, P222174,P010103, P010570

{d}nin-zi P010566

{d}nin-zil2 P010566

{d}nirah P010566

{d}]nisaba P222174, P010103, P010566, P010570

{d}NU11-e2#-nun#-ta-e3(|UD#.DU#|)#P010103

{d}NU-BU-DU P225925

[{d}]nu-dag-KI# P225958

{d#}nu#-gal P225958, P225959

{d#}nu-kiri6 P225958

{d}nu-musz-da P010485, P010505, P221638, P010570

{d}nu-musz-da P010570, P010705

{d}nun#:ki:gar:TAB#? P010103

{d}nun-a-gal2# P010103

{d}nun-gal#? P010566

{d}nun-giri17-zal! P010566

{d}nun-idim(LAK4) P010566

{d}nun-nun P010566

{d}nun-sze3-<UD>-nu-u3-DU P010566

{d}nu-nus-du10 P010566

{d}nu-nus-gal P010566

{d}nu-nus-gu2-nu P010566

{d}nu-nus-tur3 P010566

{d}nu-nus#-x P010566

{d}nun-[x] P010566

{d}nusku P020573

{d}NU-SZID# P225925

{d}nu-szu2-DU P010566

{d}nu-szum? P271228

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 27, 2012 18:37:07 GMT -5

P

{d}{pa}PAP-bil-sag P225958

{d}PA P221480

{d}pa-bil3-sag P221796, P221673, P220763

{d}pa-bilx(|GESZ.PAP.BIL|)-sag P010566

{d}PA-GAL-|URUxX| P225925

{d}PA-igi-du P220703, P220763, P221730, P221362, P220703

{d}PA-KAL P220703, P221730

{d}PA-nam2 P221800

{d}PA-nun-KID2!?-x P010566

{d#}PAP-KAL#? P225958

{d}PAP-NU-x-BU?-[...]-x P225958

{d}PA-urugal2 P010566

{d}pirig-kalag P010566

{d}pirig-KISZ P010566

{d}pirig-sag-kal P010566

{d}PIRIG-TUR P010566

{d}pisan2#-mes#:unug#? P010103

{d}pisan2-mes-unu P225961

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 27, 2012 18:49:12 GMT -5

S

[{d}]{[sir2]-sir2#}AB P225961

{d}sag:ku5 P010103

{d}sag-ga2{muszen} P010566

{d}sag-SAL4-x P010566

{d}SAHAR-LAK651 P010566

{d}SAL-KU#?-BA P225959

{d}saman3 P010566

{d}saman3-a2-a:zu5 P010103

{d}saman3-a2-zu P010566

{d}saman3-sukkal P010566

{d}samanx(|BU.NU.NUN.X.ESZ2|)# P010103

{d}samanx(|BU.NU.NUN.X.ESZ2|)#-sukkal P010103

{d}samanx(|SZE.NUN.SZE3.BU|) P221796, P227557, P222604

{d}SANGA P010566

{d}SAR#-GI-ME-RU P225958

{d}SAR-da P010706

{d}si4#?-e2-da P010566

{d}si4-[e2?]-E2-NUN P010566

{d}si4#-e2-E2-NUN-ta-e3 P010566

{d}si-bi2 P221476, P221670, P247619, P221697, P221695, P221371

{d}sig17{muszen} P010566

{d}SIG4 P020586

{d}sikil-a-x P010566

{d}sila4-dah P010566

{d}sila-gaba-kul-aba4 P010566

{d}SUD2# P225925

{d}sud3 P010485, P010501, P225931

{d}sud3-anzu P010019, P010501, P010700

{d}sud3-anzux(IM){muszen} P010532

{d}suen P020413, P010103, P010570

{d}sur-ta P010562

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 29, 2012 15:47:44 GMT -5

SZ

{d}{sze3}szer7 P010566

{d}{sze3}szer7-da P020413, P315467, P221480, P221485, P220689

{d}{szu}szaganx(AMA){gan} P010975, P010501

{d}|SZE+LU3| P225958

{d}|SZITA.GISZ.TUG2|(|SZITA+GISZ+NAM2|)-e2-nun P225961, P010103

{d}|SZITA#+ME#|-GUR7 P225925

{d}sza3-zu P010019

{d}sza#-gan-x P010103

{d}szakir(|DUGxNI|) P010085

{d#}sza-ma-da# P225958

{d}sza-ma-gan P225858

[{d}]sza#-ma-szu#? P225959

{d}szara2# P010103

{d}sze3-nir P010103, P225961

{d}szeg9-nam-DU P010566

{d#}sze-gu:na P225958

{d}szerrida(|UD.AN.UD|) P010566

{d}szesz-ib-gal P010566

{d}SZESZ-IB-gi6 P225958, P010103

{d}SZESZ-KI P010777, P010982, P011034

{d}SZIM-KI P010566

{d#}szu#:usz#:urugal2# P225958

{d}szuba3(|MUSZ3.ZA(LAK798)|) P010103, P225961

{d}szuba3-MUSZ3-KUR P225959

{d}szubur P011034

[{d}szu]-gal# P225959

{d}SZU-KAL P222463

[{d}]szukurx(|DUGxNI|) P010600

{d}szul P010501

{d}szul-|MUSZxPA| P221797, P220697, P220703, P221730, P222364

{d}szul-|MUSZxPA| e2-mah P220703, P221730, P221362

{d}szul#-EDIN# P225958

{d}szul-ga-me P020586

{d}szul#-LAK4b P225958

{d}szul-LAK4b-an P225959

{d}szul-pa-e3 P220763, P220821, P222174, P010570

{d}szul-pirig P225961

{d}szul-sza3-ga P222364

{d}szul-sza3-ga-na P220704, P220868, P222604

{d}szul-sza3-na P010566

{d}szul-szag4-na P225958

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 29, 2012 15:52:44 GMT -5

T

[{d}]tab P222174, P010870

{d}TAG-nun P010979

{d}TE@g#?-xP225958

{d}temen#-ku3# P225958

{d}ti-ge6-ga P010566

{d}tir P010562

{d}TIR-[...] P010566

{d}tu P222174, P010570

{d}tu!-dim2? P010566

{d}TUM P010103

{d}tu-sag P010566

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 29, 2012 16:08:18 GMT -5

U

{d#}|U.U.U|#-gi#? P010103

{d}|U.U.U|-UD-NUN P225958

{d}|UR2xUD| P010566

{d#}|UR2#xUD#|(LAK480) P225931

{d}U2-|(SZE.NUN&NUN)%(SZE.NUN&NUN)| P225925

{d}u3 P010566

{d}u3-du10 P010566

{d}u3-TAR? P010566

{d}u4-gur P225958

{d}UB3 P010566

{d}UD-KA P010566

{d}UD-ni3?-x-(x) P010566

{d}UD#?-PA P010566

{d}UD-sag-kal P225961, P010103, P010566

{d}UD-su-buru4{muszen} P010566

{d}UD-TAK4-ALAN P225961, P010103

{d}UD-TAR P010103

{d}ug-banda3{da} P010566

{d}ukken-du10 P010566

{d}UL-idim(LAK4) P010566

{d}um-a#? P010566

{d}umbisag2 P010566

{[d]}um#-hur{muszen} P010566

{d}um-me P010566

{d}um-nun P010566

{[d]}ur-[x]-ra# P010566

{d}ur2-nun-ta-e3-a P222604

{d}ur3#-|BARxTAB| P010103

{d}ur3-bar@gP010566

{[d]}uri3-[gal?] P010566

{d}uri3-mu P271228

{d#}UR#?-NI P225958

{d}URU-GA-GAL P010532

[{d}]UR#-URU-RA P225958

{d}uszum-gal-a-da P010566

{d}uttu(|TAG.NUN|) P010021, P222174, P010570

{d}utu P221800, P221798, P220868

{d}utu-anzu2{muszen} P220786

{d}utul2# P010566

{d}utul2-kul-aba4# P010566

{d}utu-lugal P010570

{d}utu-usz-x-lamma P010102

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 29, 2012 16:10:14 GMT -5

Z

{d}{za}za-gin3 P010570

{d}za-ba4-ba4 P010102, P010566

{d}zax(LAK383)-nun P010566

{d}za-za-gin3 P222174

{d}za-za-ri2 P222604

[{d}]ZI#-NA#-|LAGABxHAL|# P225958

{d}zum-nun P010566

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Sept 11, 2012 10:12:33 GMT -5

It is clear that not each divine name in these lists represents a unique god/goddess. Also some of these name may actually be personal names. Some of them are titles of gods, like for example {d}nin-eb-gal, which seems to be a title of Inanna, others may be personal names. I did a bit of research in the cdli on {d}nin-eb-gal, and found out that e2 eb-gal (temple of the great oval) was the Eanna temple of Inanna in Uruk. In the texts we find {d}nin-eb-gal and {d}eb-gal, possibly titles of Inanna, but also {d}inanna eb-gal and {d}szara2-eb-gal. Shara is a god often associated with Inanna. Speaking of Inanna, on a tablet from Mari i found {d}|MUSZ3.USZ| the male Aštar (Ishtar/Inanna). Some tablets that caught my attention because they are full of godnames: www.cdli.ucla.edu/P010103www.cdli.ucla.edu/P225958www.cdli.ucla.edu/P225959www.cdli.ucla.edu/P225961www.cdli.ucla.edu/P010566Also very useful is this page with a Gudea statue, because the text is translated and contains some titles of gods. www.cdli.ucla.edu/P232275 |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 30, 2012 12:57:06 GMT -5

taken from:

Mario Liverani, Uruk, the first city

4.Politics and Culture of the Early State

4. Ideological Mobilization

Inevitably the extraction of resources, upon which the complex society was based, was painful. It could not realize itself without the use of factors that transcended the natural tendency to self-sufficiency and self-reproduction. Those would range from physical coercion to ideological persuasion. They focused on a higher interest, which was not immediatly visible to the single individual-that is, the comprehensive development of the system. The unequal access to resources between various groups, and the imbalance between giving and receiving, must have been the principal problem that confronted the emerging state, to a degree much greater than in an egalitarian society.

...

First of all, it should be noted how the urban revolution, with its increased labor specialization, was reflected in the emergence of a polytheistic religion. Religiosity that focused on the single problem of reproduction, be it by humans, animals, or plants, was more suited to a Neolithic society. With the urban revolution an entire pantheon was conceptualized, which was internally structured along the lines of human relations of kinship, hierarchy, and functional specialization. In short, there was one god to supervise each type of activity: one for agriculture, one for herding, one for writing, one for medicin, and so on. All gods collaborated, whatever be their rank. Also their decision-making structure was clearly anthropomorphic in character. It had a supreme deity and a divine assembly. This assembly did not refer back to an assumed stage of pre-monarchical primitive democracy (as was stated in the famous theory by Thorkild Jacobsen), but to the everlasting assemblies with local jurisdiction.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 16, 2013 12:13:59 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 16, 2013 12:20:18 GMT -5

Some of them are titles of gods, like for example {d}nin-eb-gal, which seems to be a title of Inanna.

I did a bit of research in the cdli on this one especially, and found out that e2 eb-gal (temple of the great oval) was the Eanna temple of Inanna in Uruk. In the texts we find {d}nin-eb-gal and {d}eb-gal, possibly titles of Inanna, but also {d}inanna eb-gal and {d}szara2-eb-gal. from: Gebhard J. Selz ENLIL UND NIPPUR NACH PRÄSARGONISCHEN QUELLEN [probably 1992] translation may follow   |

|

darkl2030

dubĝal (scribes assistent)

Posts: 54

|

Post by darkl2030 on Jan 17, 2013 5:03:20 GMT -5

Great information Sheshki, I will have to find that article. I can try to provide a brief summary for the non-german speakers that maybe sheshki or others can add to if they see fit...

Selz sees two main cultic circles in prehistoric Mesopotamia: that of Enki and centered around Eridu and that of Inana centered around Uruk, the one Enki being the more ancient. For Enki he bases this not merely on the late literary sources of OB times, but on the widespread existence of abzu-shrines throughout all of Babylonia, in all the main city states (since Enki, is of course, king of the abzu).

The early importance of Inana is shown not only in the Uruk textual and material evidence, but also in the fact that shrines to Inana existed throughout Mesopotamia. She played a particularly important role in Lagash, where her temple district was called Eanna, named after the one in Uruk in what is apparently a reflection of the Uruk expansion. Her temple itself was known as "ibgal" and there were many other "ib" shrines throughout the whole province. To the information given by Selz I can also mention the fact that a "clan" of Inana bearing her "standard" (a lioness) was present at the dedication of Gudea's Ningirsu temple (the other two were that of Ningirsu and Nanshe).

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 17, 2013 9:07:06 GMT -5

Thank you for the brief summary. Here is another piece of article if you feel motivated  Something i found in another Selz article concerning Elamite influences on the Presargonic Sumerian pantheon. from: G.J. Selz "`ELAM´ UND `SUMER´" - SKIZZE EINER NACHBARSCHAFT NACH INSCHRIFTLICHEN QUELLEN DER VORSARGONISCHEN ZEIT  |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Jan 17, 2013 15:01:54 GMT -5

Hey Sheshki / DarkL: Some interesting stuff here for sure. Well Selz' articles are now very accessible thanks to his academia.edu profile, where one can download much of this content: univie.academia.edu/GebhardJSelzOn a related note Selz expressed these ideas in an email one time: "We have indications that Inanank and and Enkik belong to the earlier stratum of Sumerian religion, the former as the astral deity, the latter connected with water and irrigation and other techniques. It is for chiefly political reasons that they were moved to become stadtgottheiten (under various names)." The notion that the dominance of Enki and Inanna as religious powers preempts Enlil occurs in earlier Sumerological literature as well, although without some of the specific justifications we see in the above sources. While the argument about spread of abzu and ib shrines seems to have great merit, a degree of caution has to be used when gauging early religion based on OB source materials. The debate over the time of the emergence of Enlil (a foreign god?) would have a big impact on this, the latest attempt to summarize that debate appears in Wang 2011 (although this work could not be overly conclusive in my opinion, due to complexities.) |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 6, 2013 14:45:14 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 6, 2013 14:50:36 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 7, 2013 14:47:37 GMT -5

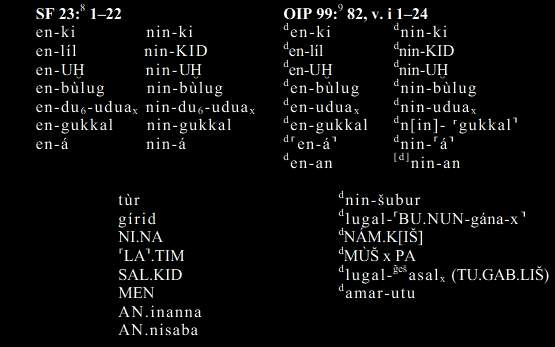

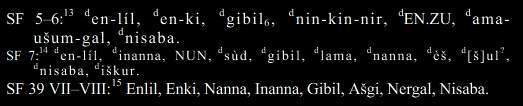

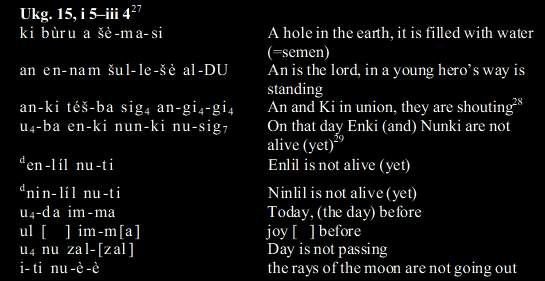

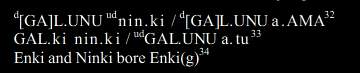

From: Acta Antiqua Mediterranea et Orientalia, Band 1 Some Early Developments in Sumerian God-Lists and Pantheon by Peeter Espak Abū Salābīkh and Fāra God ListsSF 23 list from Fāra shows seven divine pairs headed by Enki and Ninki, followed by Enlil and Ninlil, then five en and nin pairs.  Similar order is followed in the Abū Salābīkh list with slight variations adding a pair en-an and nin-an. In both lists, the major gods of Sumer appear after the en and nin pairs and the first divine figure coming after the primordial gods seems to be the mother-goddess (tùr and dnin-šubur). The Abū Salābīkh list adds den-an and dnin-an to the seven pairs of the Fāra list. It might be a theological speculation to adjust the system of the list with the understanding that world was created by the intercourse of An and Ki. When the cult of the mother-earth Ki and the great sky-god An had already been overshadowed by the later more artificial and scribal mythology, it could be imaginable to guess, that in this list the scribe refers to den-ki – dnin-ki and den-an – dnin-an as some sort of primordial powers manifested in the images of earth and sky. However, this does not explain the nature of en-ki and nin-ki in other texts where en-an and nin-an are never mentioned. Other lists such as SF 5–6, SF 7 and SF 39 VII–VIII both start with Enlil whereas the second and third place is held by Enki or Inanna:  SF 1 and Abū Salābīkh god list seem to begin with An and are then followed by En-lil, Inanna or Ninlil, and Enki:  Three different traditions of god lists seem to exist at the same time during the composition of Abū Salābīkh and Fāra texts. The first starts with Enki and Ninki followed by Enlil and Ninlil, altogether seven en and nin pairs. These lists also differ in a sense that one list adds a pair of en-an and nin-an to the end of en and nin pairs. Identification of the primordial Enki with the great Sumerian god Enki(g) in some level of thinking seems also possible. The second group of the lists (SF 5–6,SF 7, SF 39) has Enlil heading the row of the gods followed by Enki(g) or Inanna.The third group (SF 1; OIP 99, 82, 1–9) starts with An followed by Enlil, then a female deity (Inanna or Ninlil), and Enki having the fourth position. This is similar to the canonical order followed by all the later Neo-Sumerian listings. Do the differing ways of grouping the gods also reflect distinct traditions in creation mythology, for example, is difficult to answer, since “phrases used to sum up these lists offer great divergences, which suggest that not even the ancient scholars were unanimousin their understanding of these lists.” There was no overall imperial pantheon in existence in the early periods of Sumerian history. The most important gods of different regions such as Enlil, Enki, Inanna (or other mother-goddesses), An and also the primordial gods Enki and Ninki were all dynamically ordered as the most im portant divine concepts in the developing Sumerian mythological system reflected in the god lists. |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 7, 2013 15:18:13 GMT -5

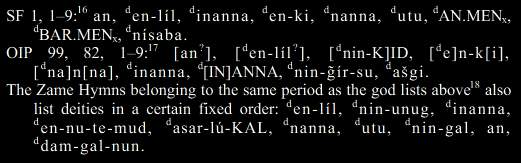

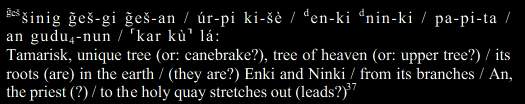

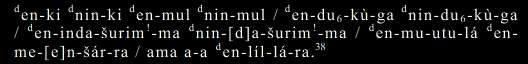

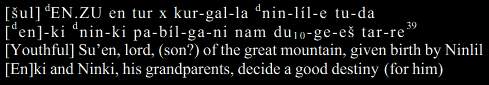

From: Acta Antiqua Mediterranea et Orientalia, Band 1 Some Early Developments in Sumerian God-Lists and Pantheon by Peeter Espak Enki and NinkiThe textual material demonstrating the genealogical relations between different divine entities in Old-Sumerian sources is in many ways confusing and the small number of texts available makes the task more complicated. Some larger preserved mythological texts though allow making some general conclusions. The fragment Ukg. 15 found from Girsu mentions the cosmic marriage of An and Ki followed by en-ki and nun-ki then by Enlil and Ninlil. An and Ki have intercourse that probably results in births of Enki-Nunki deities:  After Enki and Nunki, Enlil and Ninlil are mentioned. The text does not give any evidence whether Enlil and Ninlil are direct offspring of An and Ki or given birth by Enki and Nunki. At least one text shows Enlil separating An from Ki, and therefore it seems that two different traditions might have been in existence concerning the genealogies of deities. One relates An and Ki to the birth of all the other gods; the second tradition again places Enki and Ninki first as indicated by the early god-lists. UD.GAL.NUN texts reveal that Enki and Ninki were responsible of giving birth to Enki and Enlil as well as to other major gods of Sumer:  In some textual examples, Enki-Ninki deities seem to be in a certain way related to Enki and his city Eridu and Abzu. As was defined by Th. Jacobsen, it seems possible that Enki-Ninki deities have something to do with a sort of a chthonic or underworld cult: “This deity, whose name denotes ‘Lord Earth’ (en-ki) is a chthonic deity distinct from the god of the fresh waters Enki, whose name denotes ‘Lord (i.e., productive manager) of the earth’ (en-ki (.ak)).” The explanation seems to bequite possible in light of the Sumerian incantations from Ebla where the roots of a Tamarisk tree are equated with Enki and Ninki:  Based on that example, it can be imagined that Enki-Ninki are seen as residing inside the earth just as the roots of a tree. In Neo-Sumerian texts, the pair Enki and Ninki is listed in some literary compositions but their importance as major mythological figures seems to have been somewhat declined compared to the earlier sources such as Ukg. 15 or UD.GAL.NUN texts. The Neo-Sumerian composition known under the title “The Death of Gilgameš” seems to list them as some sort of underworld gods whom the burial offerings or gifts are dedicated. The texts describes them and the other primordial gods as “the mothers and fathers of Enlil” and “the lords and ladies of the holy mound,” so being in accordance with the earlier literary sources where Enki and Ninki were described as ancestors of all the major Sumerian gods:  One hymn of the Larsa ruler Gungunum titles the moon-god Su’en to be the off-spring of Enlil and Ninlil. Enki and Ninki are probably titled to be the grandparents of Su’en (Gungunum A, obv. 10–11):  According to the UD.GAL.NUN texts, Enki and Ninki gave birth to the succeeding primordial gods, then to Enlil, Enki(g) and also to Su’en. The Gungunum text demonstrates that Enlil is still considered to be the son of the primordial Enki-Ninki. Su’en, however, has developed into a third generation deity. This is slightly similar to the events in Ukg. 15: An and Ki have intercourse, Enki and Nunki are born who in turn might give birth to Enlil and Ninlil. Then the day (Utu) and moonlight (Su’en) are mentioned. As illustrated by a later Babylonian bilingual emesal vocabulary list, understanding the difference between Enki-Ninki and Enki-Damgalnunna/Damkina was already problematical for the Babylonian scribes: dumun-ki = den-ki = dé- ra] / dgašan-ki = dnin-ki = ddam-ki-n . At least by the present knowledge about the divine concept of Enki and Ninki, it seems impossible to determine their function in the Sumerian mythology with certainty. They might belong to a certain early phase of the Sumero-Akkadian creation mythology as the pre-eminent creator gods residing inside the Holy Mound and the earth (Ki or underworld regions). This understanding then was later adjusted with the mythology of An and Ki being the first creators. The close relation or sometimes even assimilation of Enki(g) (and also Enlil) with the primordial en-gods is also detectable but the nature of that relationship remains unclear. |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 9, 2013 13:38:36 GMT -5

From:

The God Enki in Sumerian Royal Ideology and Mythology

by Peeter Espak (PhD 2010)

8. ENKI (EA) IN THE MYTHOLOGY OF CREATION

The role of Enki in the creation of the world as well as in the creation of mankind

is one of the features that is not explicitly explained in precisely datable

royal hymns and inscriptions. What is certain, is that Enki is described as one of

the main characters responsible for natural forces, vegetation and animal

reproduction. How the world and humans were imagined emerging or being

created does not seem to be well organised or systematised in the royal ideologies

and mythologies of the different periods of Sumero-Akkadian history.

The myth about the separation of heaven and earth seems to be strongly present

in the ancient Sumerian mythological mind but the Sumerian texts only briefly

discuss the matters as introductory parts to the larger mythological narratives or

as shorter passages inside a larger text. It also seems probable that in earlier

texts the role of the mother-goddess Nintu/Ninhursag as the creator of human

beings is especially emphasised and Enki might not have been the primary force

behind the creation of mankind. Texts from Old-Babylonian Malgium, however,

already seem to refer to Enki/Ea (and probably to Damgalnunna/ Damkina)

as the main creators of man.

8.1. Enki and Ea as Cosmic Entities

Early Dynastic texts from Ebla and elsewhere always use the name den-ki for

the god while the name é-a is only present in personal names starting from the

pre-Sargonic period. The name Ea first occurs in the royal inscriptions (without

a determinative) in the later periods such as Iddin-Dagan B, 14 or Iahdun-Lim

2, 147. The Semitic name Ea bearing no determinative is in some extent comparable

with the Sumerian sky god An who can be interpreted as “the god of

heavens An” or “the heavens/sky” as natural phenomenon or geographical

region in the universe. It seems probable that for the (Western) Semites the

name Ea might have been similarly interpreted. é-a designated “the god Ea” and

the name was also used to refer to his divine element which can be determined

using the Ebla lexical lists (den-ki = ’à-u9) as spring-water or running water.

This hypothetical and watery god Hajja or Aya does not seem to be of Akkadian

origins. As C. Gordon points out, “the É in É-um / É-a reflects West Semitic ḫy

‘he lives’ or ‘is alive.’ The name É-a can only be West Semitic; for the root ḫyy

/ ḫwy ‘to live’ is replaced by an entirely different root (blṭ) in Akkadian.

Also Ubaidian and Sumerian origins of the name Ea are still sometimes discussed.

As W. G. Lambert states: “The attempt at a modern scientific etymology

of the name Ea: from West Semitic ḫy ‘he lives’ or ‘is alive’ cannot be

proved, and likewise the view that ‘Ea can only be West Semitic’. Although

not proven with certainty, the origins of the name Ea from the root ḫyy and its

possible West Semitic character are the only scientifically acceptable solutions

at the moment.

If “the Syrian É-a was not the god Enki of Sumer, but a genuine Amorite

divinity, whose indigenous name was Aya” as is probably claimed by J.-M.Durand

in his "La Religion amorrite en Syrie à l’époque des archives de Mari",

this hypothetical West Semitic god may have represented some sort of

primordial mythological waters or the “waters of the universe.” The other

option would be to consider that god representing the overall concept of running

water of rivers and springs for the Semites.

The god Enki(g/k) cannot be described as a “primordial element” or a symbol

representing certain clearly definable numinous force. Attempts at interpreting

his name have run into serious difficulties and by the modern state of knowledge

it is usually referred to as Enki(g) of unknown meaning (and origins).

The main reason for denying the existence of ki (“earth”) in Enki’s name is the

fact that the name obviously represents an entity en-ki(g/k) not related to

Sumerian ki. This fact is usually augmented with statements that the cosmic entity Ki

is not a suitable region for the god whose primary area is the (sweet)

waters or the under-earth ocean Abzu. Analysis of available Sumerian

sources does not support this kind of understanding. Enki is the manager or en

of the fertile earth and his region Abzu is situated under or inside that earth Ki.

One probable way out of this problem was offered by K. Butz: “Der Auslaut -g

in En.ki.ga, er tritt nicht immer auf, findet sich auch in ki.in.dar ‘Erdspalte.’ Es

ist demnach wohl *kig bzw. *ki anzusetzen.” When to analyse ki-in-dar in

different contexts it seems to be almost synonymously used with ki-in-du both

are translatable as “earth hole,” “earth starch” referring to something inside (or:

near the surface, in the boundaries?) of the earth as the following examples

seem to indicate:

Inanna and Ebih 83:

kur-kur-ra muš ki-in-dar-ra-gen7 šu `u-mu-da-dúb-bé-eš

Let him pull out (=destroy) the enemy lands (or: mountains) just like a snake in

(or: from) the earth hole

Hendursaga A, 94:

ki-in-du kù-ge ¡ál tak4-tak4-[...]

(so that) the holy earth holes will be opened up

The names Ea and Enki are not associated and probably represent two different

ancient gods (or divine concepts). Their complete assimilation is visible only

from the Old-Babylonian period onwards.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 13, 2013 12:33:19 GMT -5

From:

The God Enki in Sumerian Royal Ideology and Mythology

by Peeter Espak (PhD 2010)

Chapter 1 EARLY DYNASTIC PERIOD

1.9. Conclusions

Enki is worshipped in all the major Sumerian states although the textual

material from Umma, Ur or Uruk is not numerous compared to the royal

inscriptions of Lagaš. G. Selz has concluded that the gods Enki and Inanna were

universally honoured in Sumer and Akkad, as indicated by the existence of ibgal

shrines for Inanna and abz/su temples for Enki in early Mesopotamia: “Die

hohe kultpraktische Bedeutung beider Gottheiten in der präsargonischen Zeit ist

offenkundig und der Schluss auf eine ursprunglich Suprematie beider zumindest

naheliegend.” The emergence of the importance of Enlil might then be

explained by that god being a central religious power behind an ancient political

union with its meeting place in the city of Nippur. Enlil’s only function in all

the Early Dynastic royal inscriptions is the nomination of the king, giving

strength or power to the king or granting the king the sceptre.

The lexical list from Ebla translates den-líl as il-ilu “god of the gods” or

“head of the gods.” Already Eanatum legitimises his treaty with the hostile

Umma by mentioning the god Enlil as the first granter of the oath. The origins

of that hypothetical political god are hard to determine and all the available

different solutions are speculative. The same must be said of the theories

considering Enki the “original head” of Sumerian pantheon. The inscription

Giša-kidu 2 seems to picture Enki as a more important god compared to Enlil.

This indicates that in Ummaite theology, the Lagašite tendencies to list Enlil as

the preeminent god might not have been present. But even though Enki is

mentioned before Enlil, Giša-kidu still titles himself énsi kala-ga den-líl-lá-ke4:

“mighty city ruler of Enlil.” This is an indication of the fact that a ruler had to

be approved by Enlil (i.e. the priesthood of Nippur) to be legitimate.

The most important characteristic of Enki from the whole period is his ability to

grant ĝéštu (“knowledge / understanding / wisdom”) for the king. Enki is

connected to Abzu, Engur and Eridu and is titled the king of Abzu or Eridu.

Inscriptions associate him with the reeds. Enki is less important than Enlil in

terms of royal ideology, but he is always in a prominent position when all the

major gods of Sumer are listed.

Chapter 2 THE DYNASTY OF AKKADE

2.3. Conclusions

Only the inscriptions of Naram-Su’en mention Enki, and the information about

the role, status or character of that god in Akkadian ideology remains obscure.

The god is always written using his Sumerian name; only in personal names is

the name Ea ever used. Enki is mentioned as capable of blocking the waters of

irrigation canals in a curse formula of Naram-Su’en. Enki’s association with

canals is paralleled with the appearance of the god with streams of water in

Akkadian glyptic art. This is in accordance with the description of Enki’s name

in Ebla texts titling him most probably as “the living.” Enki is not among the

most important gods for the Akkadian rulers and his position seems to be less

important than that of several presumably Semitic deities such as Inanna/Aštar

or Utu/Šamaš.

Chapter 3 THE SECOND DYNASTY OF LAGAŠ

3.4. Conclusions

The texts of the Second Dynasty of Lagaš continue the traditions of Early

Dynastic royal inscriptions in describing the overall canonical pantheon of

Sumer and the local Lagašite gods. The supreme status of An and Enlil is

recognised in the inscriptions of Gudea and they are mentioned before the gods

Ningirsu and Nanše. Enki is listed after the mother-goddess Ninhursag. The Ur-

Bau inscription 5 however demonstrates an older tradition listing Ningirsu and

Nanše first. Also Enki is mentioned after Bau in this inscription. It seems that

the gods of Enki’s circle have been adopted to the Lagašite pantheon in the

earlier periods and the listing of An and Enlil as supreme might be a newer

tradition.

Enki’s main function in the Gudea’s Temple Hymn is to give practical

advice or help in different stages of construction. He gives “plans” (ĝeš-ḫur)

and “oracular pronouncements” (eš-bar-kíĝ) for the benefit of the construction

works of Ningirsu’s temple. Enki’s relation to all kinds of practical skills is

probably reflected in Enki’s title or in the name of his temple ĝeš-kíĝ-ti:

“craftsman” / “workshop.” Enki’s close relation to Nanše, detectable already in

the Early Dynastic inscriptions, is also strongly outlined in the texts of the

Second Dynasty of Lagaš. A reference of the cultic journey of Ningirsu to Eridu

underlines the early importance of that city as a religious centre.

Chapter 4 UR III PERIOD

4.9. Conclusions

One of the most important developments concerning Enki in the Ur III period

sources is the change of his rank in the listing of gods. Contrary to the earlier

inscriptions, he gets the third rank in the pantheon after An and Enlil and begins

to precede the mother-goddess in the inscriptions of Ibbi-Su’en.

A similar change in rankings was already introduced in Ur-Namma C.

Starting from the reign of Ibbi-Su’en, the new order becomes paradigmatic.

The inscriptions of Šulgi show great respect towards the city of Eridu. Contrary

to the earlier traditions where the city of Nippur was always listed first as the

primordial city, Eridu gets this position. Enki is associated with canals, high

waters bringing abundance (ḫé-ĝal) and boats. Cleansing rites (šu-luḫ) and

incantations (nam-šub) are also related to Enki. Among his titles not present in

the earlier inscriptions he is called pap-gal (“older brother of the gods”) and denlíl-

bandà (“junior Enlil”). A new concept of seven me-s and seven knowledges

(ĝéštu) is mentioned in Ur III hymns.

Puzur-Inšušinak of Elam, a contemporary of Ur-Namma, lists Enki after

Enlil as the most prominent deity of Sumer and Akkad. This fact shows that

Enki was known and honoured in all the regions of the wider Ancient Near

East. In Mari, the gods Enki and El were probably seen as similar divine

concepts. The inscription of Puzur-Eštar titles Enki as “the lord of the assembly

of gods” – a title held by the god El in West-Semitic mythology. Later West-

Semitic mythological material allows the equation of their divine abodes and

their “wisdom/ knowledge” is pictured almost identically. When the creation of

mankind is in question, El and Enki are both creator-gods. This is indicated also

by the title of El “the father of mankind.” However, Sumerian mythology does

not refer to Enki as the creator of earth – as was the case with El. Enki’s role as

the creator of mankind is not attested in the Ur III sources where this function

seems to be attributed to the mother-goddess.

Chapter 5 THE DYNASTY OF ISIN

5.9. Conclusions

In the ideology of Isin, Enki’s city Eridu does not have the pre-eminent position

it had during the reign of Šulgi. In the titulary formulas of the Isin kings, the

cities are usually ordered: Nippur, Ur, Eridu, Uruk, Isin. Nippur is listed as the

ancient pre-eminent city of Enlil from where the kingship is legitimised. Placing

Ur second probably indicates the wish of the kings of Isin to show their respect

towards the previous power centre in Mesopotamia. Eridu’s third position

testifies that the city was considered among the most important centres of

religious (and also political) influence. Lipi-Eštar’s inscriptions show that he

had been crowned as king in Eridu. Uruk’s elevated status in the titles is also

notable. The god of Uruk, An, was highly praised in the royal hymns of the

kings of Isin. Enki was titled to be “the son of An;” also the mother-goddess

Uraš was described as his mother.

According to the royal hymns of Isin, Enki received his duties, me-s, powers

and all the other aspects of his nature from the gods An and Enlil. He seems to

be nominated as the head of the Anunna gods by Enlil and An. Enki is

described as receiving his me-s from the E-kur temple of Enlil. The Isin royal

hymns already refer to Enki as one of the creators of mankind. In addition, his

role is to take care of the everyday needs of the people of Sumer and to

guarantee the abundance of agricultural life. The abundance also comes through

the waters of the rivers and as rain from the sky.

It is reasonable to suggest that in addition to the city laments, several

Sumerian myths also might have originated from the mythological thinking of

Isin period. Some similarities between the Isin era hymns and Sumerian myths,

such as Enki and the World Order, Enki’s Journey to Nippur, and Enki and

Inanna, were taken into consideration. It was concluded that it is at least

possible that they might be Isin period texts. The age and provenance of the

mythological ideas, however, is not determinable with certainty.

Chapter 6 THE DYNASTY OF LARSA

6.9. Conclusions

The inscriptions of Rim-Su’en describe Enki in almost similar terms to the

inscriptions of Isin. Enki is responsible for granting abundance (ḫé-ĝál). Enki is

also described as the advisor to the great gods. He is characterised as the god

who “assigns to the living beings their share” which is similar to the texts of

Isin Dynasty praising Enki as responsible for organising the life of the people.

One noticeable aspect in Rim-Su’en’s inscriptions is that there is an inconsistency

in grouping the most important gods of Sumerian pantheon. Several

inscriptions omit the name of the mother-goddess and the “triad” An, Enlil,

Enki (and) the great gods” (an den-líl den-ki / d¡ĝir gal-gal-e-ne) is beginning to

appear in the royal ideology. This seems to be another indication of the

diminishing role of the mother-goddess in the pantheon. Enki, in turn, is listed

among the three most important deities.

Enki’s close relation with the shrine of the moon-god at Ur is detectable

based on the inscriptions of Rim-Su’en. Although it is impossible to claim that

the priests of Enki had migrated to the city of Ur, their presence there is

influential, expressed in several hymns dealing with the Eridu circle gods such

as Asaluhi and Haia (whose etymology is closely similar to that of the Akkadian

name Ea). The connection of Ur shrine and Enki’s Abzu was detectable already

in the earlier periods which does not seem to support the theory of migration of

the priesthood of Enki.

Asaluhi is identified with Marduk in Asaluhi A hymn, presumably dating to

the reign of Rim-Su’en. He is also titled to be the son of Enki and responsible

for the incantations. Asaluhi appears under the name Ilurugu, meaning “the

river of the ordeal.” The previous royal inscriptions did not mention Enki and

Asaluhi (or Marduk) together in close context and relatable to incantations.

One inscription of Su’en-kašid of Uruk titles Enki to be the eldest son of An

(dumu-saĝ maḫ an-na) in accordance with Enki’s common status as the son of

An from the Isin texts onwards. An inscription of Iahdun-Lim of Mari uses the

name-form Ea instead of Enki and titles him “Ea, the lord of destiny:” é-a šar

ši-im-tim.

Chapter 7 THE FIRST DYNASTY OF BABYLON

7.7. Conclusions

During the years of Hammurapi and his successors, the texts reveal a certain

mixture or syncretism of two different systems of beliefs. One is the system of

the Amorites and the official pantheon of the city of Babylon, the other the

canonical pantheon of the previous Mesopotamian states. The Babylonian

system seems to be more centered on the figures of Šamaš and Marduk; the

canonical Mesopotamian system around An, Enlil, Enki and also the mothergoddess.

It seems possible that the Babylonian system might have originally

considered Marduk the son of the sun-god and his consort Aya (da-a). When

Hammurapi had taken control over all the ancient Sumero-Akkadian areas, he

must have had the necessity to mix the two pantheons together in a single

imperial pantheon. The Sumerian god Asaluhi, known to be the son of Enki,

might have been equated with Marduk already in the earlier periods. The texts

of the First Dynasty of Babylon describe Marduk in similar terms as Enki was

described in the inscriptions of Isin. Marduk receives the Enlilship from the

great gods and An and Enlil. Marduk also becomes the god of knowledge and

wisdom as had previously been the role of Enki. However, in all the available

inscriptions, the importance of the previous heads of the Mesopotamian

pantheon (An, Enlil and Enki) is not overshadowed by the theology of Marduk.

The system of Enuma eliš where the other gods are symbolically described as

the names of Marduk is not reflected directly in Old-Babylonian inscriptions.

The texts from Malgium show an extraordinary devotion towards the gods

Ea/Enki and Damkina/Damgalnunna. This refers to their high importance in the

eyes of the Amorites in Mesopotamia. Whether they were simply following an

older Sumero-Akkadian tradition and to what extent does the god Ea/Enki in the

sources of Malgium and also in the texts of the First Dynasty of Babylon reflect

the concept of the hypothetically Semitic deity Ea, is hard to answer. If the two

concepts were originally significantly different, then during the Old-Babylonian

period the assimilation is already clearly attested. There is no possibility to

claim with certainty which aspects might be originally Semitic and which

characteristics should be originally Sumerian.

GENERAL CONCLUSIONS

The abundant presence of Abzu cult sites in Early Dynastic Sumer refers to

Enki’s prominent position in the archaic pantheon. When the first longer written

text appeared, the god Enlil clearly had the pre-eminent position. From the first

inscriptions onwards, Enki is pictured as the god of technical skill and planning.

Early Dynastic sources list the primordial gods Enki-Ninki as his parents. The

sources of the Dynasty of Isin, however, clearly state that his parents were the

sky-god An and the earth-goddess Uraš. The texts of the Dynasty of Akkade

begin to associate Enki with rivers and canals. During this period appeared the

flowing water motive on cylinder seals related to Enki. The Ur III period texts

describe Enki as the god of fertility and granter of natural abundance. The texts

do not relate him directly to the creation of man and this function is attributed to

the mother-goddess Nintu/Ninhursag. Among the most significant changes

during that period, Enki receives the third position in the listings of gods and

begins to precede the mother-goddess.

Enki-mythology was present already in the 3rd millennium Ebla and in the

later texts from Mari and Elam, far from the actual Mesopotamian territory. It

remains unclear to what extent the West Semitic mythology saw the god El

connected to Sumerian Enki. However, the relation or closeness of the two

divine concepts is clearly visible. The gods share the function of being the

creators of mankind. The motive of crafting mankind appears in the later layers

of Sumerian mythology and is not detectable in the Early Dynastic or Ur III

texts. Since both, El and Enki, are described as creating by handicraft and using

clay as the material of creation, it cannot be excluded that the crafting motive of

creation originally had close connections with the Semitic mythology. On the

other hand, the motive of creation by the means of copulation is present in the

earliest layers of Sumerian mythology.

The texts of the Dynasty of Isin consider Enki one of the prime forces behind

organising the natural world as well as the human civilisation. Enki is said

to be acting by the orders of the gods An and Enlil. His role as the one primarily

responsible for different purification rituals and incantations has also become

clearly attestable. The texts of Larsa start relating Enki with Asaluhi who has

already been assimilated with the Babylonian god Marduk. It seems that the

mother-goddess is continuously declining in rank and is often not listed among

the most important gods. Enki has maintained his third position. Several other

Eridu circle gods, such as Haia, are also praised by the scribes of Ur. The later

Babylonian theology brings a change to the Mesopotamian pantheon. The

ideology of Babylon tries to adjust the god Marduk into the ancient and

generally accepted Sumerian pantheon. Although Enki’s position as the father

of Marduk secures his prominent status in the theology of Babylon, it is

detectable that Marduk starts to take over the active functions of Enki. Texts

from Malgium state that Enki (and possibly his wife Damgalnunna) are the

creators of the king.

The position of Enki’s cultic city Eridu must have been extremely important

already during the Early Dynastic period. This is indicated by the references to

different cultic journeys to Eridu. However, in most of the available texts, the

city of Nippur has the pre-eminent position. It is only during the reign of Šulgi

when Eridu is listed as the first city. The texts of the Isin-Larsa period do not

consider Eridu the pre-eminent city and list it as second or third in rank.

Based on the Sumerian evidence analysed, there is no reason to directly call

Enki a water-god or a deity embodying the sweet waters. In several texts, Enki

is related to canals and is associated with fertilising floods, reeds and canebrakes

growing out of Engur. However, canals and agricultural abundance

brought by water are not the most frequently mentioned characteristics of Enki.

In addition, all these features can be attributed to several other deities of

Mesopotamia. Enki’s semen was symbolically considered to be water (of the

rivers and canals), a feature shared with the sky-god An. The fertilising water is

a divine attribute of both gods; but they cannot be considered to be “water personified.”

There is no direct evidence that the Sumerian Abzu was seen as the

(sweet-)water ocean or an area filled with water. This seems to be the case in

later Babylonian mythology. On the other hand, the entity called Engur certainly

seems to represent ground-waters or marsh-waters.

There are no textual examples or sound philological arguments available

clarifying the possible meaning of the name Enki. The Semitic name Ea is most

probably derived from the root *hyy (“to live, the living”) and refers to the

concept of running water in Semitic contexts. This interpretation cannot be

proven in absolute terms. The nature of Ea’s Semitic name allows to determine

the ancient (West-)Semitic origins of that divine concept. In the 3rd millennium

texts, the name Ea appears only in personal names. All the early mythological

compositions and royal texts use the name Enki. The complete assimilation of

the two concepts is visible starting from the Old Babylonian periods.

Based on the Sumerian royal inscriptions and myths, there is no grounds for

claiming that there was any detectable rivalry between the theologies of Enlil of

Nippur and Enki of Eridu. Enlil is the most important god in terms of royal

ideology and his priesthood had the upmost influence in the political life of

Mesopotamian. Enki, in turn, is the cultural hero of the Sumerians while Enlil is

the political and military lord representing the aspect of power. In mythological

compositions as well as in royal hymns, the theologies of Enki and Enlil are

almost always described as harmonious. Detecting the different schools of

Mesopotamian theology (Nippur and Eridu) did not seem possible based on the

available sources. All the differences in mythological accounts can be explained

as resulting from other reasons than that of the existence of two distinct schools

of mythology. However, it cannot be excluded that the priesthoods and scribes

of Nippur and Eridu might have had different mythological goals or understandings.

One apparent feature in Sumerian mythology is the fact that Enki is always

closely related to the concept of the mother-goddess. He often copulates with

different mother-goddess figures and seems to be unable to create without the help

of the birth-goddesses. The suggestion of P. Steinkeller that Enki might

have been an archaic head of the Sumerian pantheon, always paired with all the

major mother-goddess figures in different cities and regions of Sumer, seems to

be one of the most probable scenarios. Enki has all the characteristics of an ancient

Mesopotamian fertility god, who may have started losing his original

importance when the Sumerian society grew more complex, and instead of

religious-agricultural activities, the concept of divine political might was

growing more important. The origins of Enlil and his archaic nature are hard to

determine with certainty. His emerging supreme might be related to the rise of

his city Nippur to the rank of the predominant political centre of Mesopotamia.

Due to a lack of written evidence, all the solutions offered are only speculative.

Among the most important conclusions, it must be stated that contrary to the

widely shared opinion, the religious thinking of Ancient Mesopotamia reflects

continuous change. There is no constant and static divine figure Enki comparable

in similar terms in Early Dynastic mythology and the first millennium Enuma

eliš theology. Almost every period in Mesopotamian history introduces the

re-evaluation of the pantheon and new mythological ideas. The older material

is, of course, preserved in the newer thinking; however, the older periods cannot

be analysed accurately based on the information of more recent texts. Changes

in religion are often related to the political aims of a certain dominating political

power. On the other hand, the Ancient Near Eastern mythology reflects internal

mythological developments not associable with any particular political motivator.

Understanding and presenting this change of ideas and concepts was one

of the main goals of the current dissertation.

++++++

The whole document can be found at P.Espak´s Academia.edu page.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 26, 2013 15:13:12 GMT -5

Here is some information about a goddess i was unaware of so far named Lisi, who seems to have been the patron deity of Abu Salābīkh.

from:

The Name Nintinugga with a Note on the Possible Identification of Tell Abu Salābīkh

Author: Mark E. Cohen

Source: Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Apr., 1976)

We suggest that the zà-mì hymns edited by R. Biggs OIP99 hold the key to

revealing the ancient name of modern Tell Abu Salābīkh.

Noting that no other fragments of this work have appeared in either Fara or Adab,

we see no reason not to conclude that this work wasn´t native to Abu Salābīkh.

And if this be the case, then according to an analysis of the zà-mì hymns,

Lisi was the goddess of Abu Salābīkh. We base this statement upon three observations:

1) The ordering of the compilation of the zà-mì hymns:

The only other Sumerian work of a structure similar to that of the zà-mì

hymns is the Temple Hymns, edited by A. W. Sjoberg, TCS3. Tradition,

attributed the compilation and the ordering of the hymns to Enḫeduanna,

the daughter of Sargon of Akkad. The Temple Hymns conclude with a

doxology to Nisaba, the goddess of the scribal arts, in a fashion similar to

the previously discussed closing doxologies to Nisaba during the Fara

period. Actually the concluding temple hymn is to the é-a-ga-dè.ki, the

temple of A(m)ba in Akkad, the city of the redactor, Enḫeduanna. This

final position of this temple hymn thus appears to be a place of honor.

Similarly we suggest that the positioning of Lisi at the conclusion of the zà-mì

hymns to be no accident, but rather a deliberate honor bestowed upon

the goddess of Abu Salābīkh.

2) The form of the individual zà-mì hymns:

Each individual zà-mì hymn concludes with the formula DN zà-mì

"DN, praise!" However the conclusion to the zà-mì hymn to Lisi is unique:

dingir-gal-gal ama dLi8-si4zà-mì

"The great gods (and) mother Lisi, praise"

The fact that Lisi alone is deserving of being singled out from the collective

body of the great gods is obvious evidence of the special position of Lisi in

this composition.

3) The epithet "mother Lisi":

In the zà-mì hymns only three goddesses have the prestigious epithet

ama, "mother," Ningal, Nintu, and Lisi. This is not surprising with Ningal

and Nintu, yet it is slightly unexpected in the case of Lisi. Later

Babylonian tradition relegated Lisi to the status of being Dingirmaḫ's

daughter. Moreover, during this period Lisi was not identified with any

particular city. That Lisi was an important mother goddess in the Fara

period is clear. Besides our reference in the zà-mì hymns, note that in the

god lists from Abu Salābīkh Lisi occurs directly after dBIL.GI. In the god

list from Adab, Dingirmaḫ occurs in this position suggesting an

identification of Lisi with Dingirmaḫ. The proof of this identification is

VAS10 198 which has the colophon[ . . .]-dingir-maḫ-a-kam "a[, . . .]-(song)

to Dingirmaḫ." The opening lines of this work equate the goddesses

Dingirmaḫ, Ninmug, Ninḫursag and Lisi. This might well explain the

attraction of the Keš temple hymn for the people of Abu Salābīkh, for they

saw the goddess Nintu/Ninḫursag of Keš as another form of their goddess,

Lisi. Lastly note that the naming of a month as ezen-dLi8-si4 indicates the

importance of Lisi at one time. Thus we have a portrait of a goddess who

was extremely important during the Fara period, yet from the Old

Babylonian period on she is city-less, finally relegated to the position of a

daughter of the mother goddess. To us this indicates that Lisi's native town

no longer existed by the Old Babylonian period.

Summing up, the excavations at Abu Salābīkh, D. Hansen states,

"occupation [at Abu Salābīkh] ceased at the end of Early Dynastic IIIa or

shortly thereafter, and the site was never reoccupied." Thus if we are to

uncover the ancient name of Abu Salābīkh we must exclude any

geographical name that occurs in an economic text from the Sargonic

period onward. It is our suggestion that the ancient name of Abu Salābīkh

occurs in the zà-mì hymn to Lisi. Note that at least twenty-six

(and we're sure more were we able to translate all the zà-mì hymns)

zà-mì hymns name the deity's city in the very first line.

So too in the zà-mì hymn to Lisi the very first line indicates the name of

Lisi's city "Giš-gi ki-du10, Gišgi the good place."

Lastly, note that in four pre-Sargonite texts the

geographical name Gišgi occurs. All references are from Nippur,

suggesting Gišgi might be situated near Nippur, as is Abu Salābīkh.

Therefore we believe that Tell Abu Salābīkh is ancient Gišgi.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Mar 3, 2013 9:50:12 GMT -5

Frank - This is an excellent addition!  I love Cohen's article and his reasoning here. Could Gišgi be the name of ancient Abu Salabikh? Possibly. I think I remember Frayne saying that scholars were split by Cohen's suggesting,some withholding support for the idea. But this is normal of course, nothing is uncontentious in Assyriology (a field where the majority of 'facts' are not provable). I have encountered Lisi here and there and she definitely merits interest as a major goddess who has been forgotten. I will try and post below a collection of identifications of the gods of the zà-mé hymns I put together for a paper. I've just read about the existance of a emesal lamentation 'The lamentation for the goddess Lisin' which I think is the same as Lisi. The lamentation may be OB and from Larsa. This text was treated by Kramer in his article Lisin, the Weeping Mother Goddess. A New Sumerian Lament which appears in G. Van Driel et al (eds) ikir šumim. Assyriological Studies Presented to F.R. Krause on the Ocassion of His Seventieth Birthday." |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 17, 2013 8:25:32 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 20, 2013 13:12:26 GMT -5

|

|