|

|

Post by sheshki on Nov 20, 2013 16:55:45 GMT -5

from Die Göttin Ninegal/Bēlet-ekallim nach den altorientalischen Quellen des 3. und 2. Jt. v. Chr.by Geetā De Clercqchapter 2.2.2 Die Šurpu-Beschwörung>>>LinkZu den oben vermerkten Gottheiten lässt sich folgendes sagen: Die Gottheiten Panigarra und EN.KA 2.GAL, der "Herr des großen Tores bzw. des Stadttores", sind sehr selten bezeugt, so dass ihre Funktion ungewiss bleibt. Enkimdu ist der Gott der Bewässerungsanlagen und des Ackerbaus. Gula ist eine Heilgöttin, die auch mit Ninisina gleichgesetzt wurde; Laḫmu ist wahrscheinlich ein Monster, dass mit Toren verbunden wurde. Rammanu bedeutet "der Brüller" und könnte daher mit dem Wettergott Adad in Verbindung stehen. Rammanu ließe sich auch mit Erdbeben verbinden. Auch Riḫşu könnte auf eine Verbindung mit Adad hinweisen; der Name selbst bedeutet "Überschwemmung" (AHw), sowie "Vernichtung" (CAD R 335-336). Nisaba ist die Getreidegöttin und die Schwester Ningirsus (der mit Ninurta gleichzusetzen ist, cf. Weidner Liste II 2.1.2); Ereškigal ist die Herrin der Unterwelt und Lugalgudua ist als Beiname für Nergal, den Gatten der Ereškigal, bekannt. |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 15, 2013 14:56:37 GMT -5

from Die Göttin Ninegal/Bēlet-ekallim nach den altorientalischen Quellen des 3. und 2. Jt. v. Chr.by Geetā De Clercqchapter 2.3 Die Genealogie der Göttin>>>LinkDie Frage nach der Genealogie der Ninegal/Bēlet-ekallim ist nicht eindeutig zu beantworten. Wie bereits ausgeführt, dürfen die ältesten Belegstellen als Zeugen einer selbständigen Göttin, die den Namen Ninegal trägt und die den Königspalast verkörpert, aufgeführt werden. Von dieser Gottheit ist wenig bekannt und auch Informationen über die Genealogie fehlen ganz. Seit Ninegal, "Palastherrin", für eine Sonderform der Inanna verwendet wurde, teilt unsere Göttin die Genealogie mit dieser und ist demnach Tochter des Mondgottes Su'en/Sîn und der Mondgöttin Ningal und Schwester des Utu/Šamaš. Ihr Geliebter ist Dumuzi, ihre Schwägerin Geštinanna und ihre Botin Ninšubur. Eine andere Quelle verwendet die Bezeichnung Ninegal in einem ganz anderen Kontext, nämlich als Anrede für Nungal, die Göttin des Gefängnisses. Folglich wird die Genealogie des Namenträgers auf unsere Göttin übertragen: Sie ist nun das Kind des Himmelsgottes An und der Unterweltgöttin Ereškigal und verheiratet mit Birtum. Weiterhin lässt sich eine interessante Tradition aus den Texten Nordmesopotamiens ableiten: Hier erscheint Ninegal neben dem Stadtgott von Dilbat, der den Namen Uraš trägt. Diese Verbindung ist einzigartig, denn zum ersten Mal bekommt Ninegal einen Partner zugeordnet. Die Tatsache, dass Uraš einen Sohn namens Lāgāmal hatte, liefert allerdings keinen ausreichenden Beweis dafür, dass Ninegal dessen Mutter war. Schließlich bleiben uns noch einige Daten, die nur in den oben besprochenen Götterlisten verzeichnet sind: So verfügte Ninegal über einen Wesir, der den Namen Diku(m) trägt; eventuell bestand noch eine gesonderte Ninegal-Gestalt ('Ninegal der Geborgenheit'), aber dies bleibt noch relativ problematisch. |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 16, 2013 13:01:22 GMT -5

from Die Göttin Ninegal/Bēlet-ekallim nach den altorientalischen Quellen des 3. und 2. Jt. v. Chr.by Geetā De Clercqchapter 1.3.2.1.2 Die Verehrung im Palast>>>LinkNach Sallaberger sind bestimmte Götterreihen wie u. a. Inanna-Ninegal-Utu oder Ninegal- Inanna-Ninsun, wobei die Reihenfolge nicht festgelegt ist, weitere Indizien, die die Identifikation von Palastritualen erlauben. Ein Palast als Kultort für die Versorgung von Gottheiten und für monatliche Feierlichkeiten kann in der neusumerischen Zeit in verschiedenen Orten belegt werden; hierbei kommen vor allem die Palastanlagen in Ur, Uruk und Nippur in Betracht. Mit Sallaberger wird bei fehlender Ortsangabe wahrscheinlich der Palast in Ur gemeint gewesen sein. ... Wichtige Befunde aus den Palastritualen sind folgende: • Die meisten Palastritualtexte stammen aus der Zeit Šu-Su'ens. Es kann jedoch an der Überlieferung liegen, dass aus den Regierungszeiten anderer Könige weniger Texte erhalten sind. • Die sizkur 2 ša 3 e 2 -gal hängen manchmal mit bestimmten Festen (Vorabendfeier und Mondfeier, Totenopferkult) zusammen. • Die dargebrachten Opfer bestehen überwiegend aus Kleinvieh. • Ninegal kommt in festen Götterreihen vor, wobei die Reihe 'Inanna-Ninegal-Utu' die am häufigsten belegte ist; daneben stehen andere Reihen wie 'Inanna-Ninegal-Ninsun', 'Inanna-Ninegal-Dagan', 'Utu-Ninegal-Nisaba', in denen entweder Inanna oder Utu von einer anderen Gottheit ersetzt werden können (Ninsun, Dagan, Nisaba). Außerdem sind noch andere Reihen bezeugt, die palasttypische Götter neben Ninegal stellen (u. a. Nanna und Geštinanna). Diese Texte tragen zusätzlich die kennzeichnende Formel 'sizkur 2 ša 3e 2-gal', so dass sie zweifelsfrei als Palastrituale zu betrachten sind. • Über die Gestalt der Ninegal sagen die Texte nicht sehr viel aus, jedoch ist zu beachten, dass sie in den Texten neben Inanna, also als selbständige und nicht mit Inanna identifizierte Göttin, erscheint. Wegen des Auftretens der Ninegal neben einer Inanna 'ša 3e 2-gal ' ist sie auch nicht mit der Gestalt einer 'Inanna des Palastes' gleichzusetzen (Cf. zu dieser Zeit auch in Mari, III 2.2.2.1.1). • Die Opfer wurden in den Palästen in Ur und Nippur dargebracht. |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Dec 19, 2013 9:13:14 GMT -5

Sheshki - I am glad you brought de Clercq's 2003 dissertation to our attention. When it comes down to it, Ninegal seems to have been an important goddess in her own right who often escapes out attention, likely because she was equated with Inanna at some point in antiquity. Due to the loss of her distinct character, she is likely difficult for modern scholars to discuss, unless with a microscope like that used by de Clercq. Here is a collection of general views on the goddess collects by D. Franye, an entry from his forthcoming dictionary of gods and goddesses:

Nin-egal(a) (Sumerian), B@elet-ekalli(m) (Akkadian) (M) A Sumerian/Babylonian goddess. Nin-egal means “Lady of the Palace (literally “Great House”).” Originally a separate deity, but later often equated with Inanna/I@star, so that her name became a name of Inanna/I@star. It was also a name of other major goddesses. For instance, the patron goddess of prisons Manun-gal or Nungal received the epithet on a few occasions and so was “Lady of the Big House,” the “Big House” being the prison. However, Nin-egal’s main function was likely as patron of the royal palace. Her task was, then, to ensure the ruler’s position, as well as guarantee the economic well-being of his seat of government and home. At Mari, B@elet-ekalli(m) had her shrine inside the palace. Nin-egal’s spouse was Ura@s, the tutelary deity of the city of Dilbat, and her vizier was the judge Diku. In one of the Sumerian love songs in which the lovers compared their pedigrees, Dumuzi called Inanna Nin-egala, and the name occurs often in the songs as a name of the goddess. In the Sumerian poem “Gilgame@s and the Bull of Heaven,” Nin-egal and Inanna appeared to be interchangeable. The Sumerian king @sulgi (2094-2047 BCE) mentioned Nin-egal in a self-praising hymn. An Akkadian treaty appealed to Nin-egal and her husband Ura@s to preserve the integrity of the treaty. B@elet-ekalli(m) was mentioned in two dream revelations sent in letters to Zimr@i-L@im, king of Mari (ca. 1775-1761 BCE). Nin-egal was worshiped in every major Mesopotamian city. She had a temple at Ur, where her cult was celebrated at least in the Ur III Period. At Umma, also in the third millennium BCE, clothing was provided for Nin-egal for the New Year Festival. At Laga@s in Gudea’s time (second millennium BCE), she was called “Lady of the Scepter” and received offerings in her own temple. B@elet-ekalli(m) had temples at Ur, Dilbat, Larsa, A@s@sur, and Qatna, a city of which she was patron deity. She was worshiped at Nippur and Babylon. At Mari, where she was regularly presented with an offering of oil, she was the patron of the royal family. She was also honored in Elam and at Emar. (Foster 2001: 225; Frayne 2001: 123; Leick 1999: 153, 181-182; Leick 1998: 25; Litke 1998 (1959): 155; Sefati 1998: 197; M. Cohen 1993: 130, 156, 168, 243, 290-291, 347; George 1993: 32, 88 #320, 110 #604, 138 #939, 166 #1373; Tallqvist 1974 (1938): 401; Kramer in Pritchard 1969: 586, 637; Moran in Pritchard 1969: 630, 631; Reiner in Pritchard 1969: 533; Behrens and Klein in Reallexikon IX: 342-347)

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 19, 2013 19:25:11 GMT -5

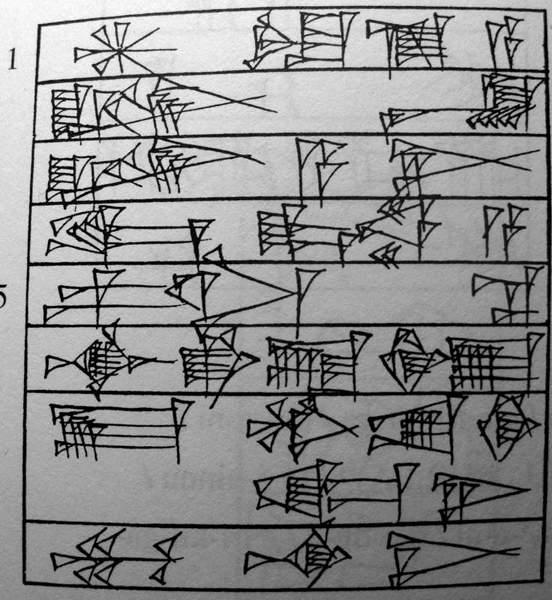

Here is a list of deities in Emesal. >>>LINK |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 29, 2013 15:35:16 GMT -5

Ninegal was also worshipped in Elam possibly from URIII times down to the 14th/13th century BCE. According to textual evidence there has been a temple in Susa and also at least one other in Tschoga Zambil. For more information read Die Göttin Ninegal/Bēlet-ekallim nach den altorientalischen Quellen des 3. und 2. Jt. v. Chr.by Geetā De Clercq>>>Link |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 4, 2014 15:40:58 GMT -5

Here is a loose translation of the summary of Die Göttin Ninegal/Bēlet-ekallim nach den altorientalischen Quellen des 3. und 2. Jt. v. Chr. by Geetā De ClercqDevelopment Over TimeShe appears earliest in the Fāra lists, then throughout all periods up to Late Babylonian texts from Uruk. Therefore, she is visible for nearly 3000 years in the Near East. The peak period for her cult was the 2nd millennium. Her Spatial DevelopmentThe distribution of her cult reached from southern Mesopotamia east to Elam, northwest and west via northern Mesopotamia to Asia Minor, the area that now is Syria and the Levant. She appears in all greater cities and archives except in Ebla. Her CharacteristicsFirst, Ninegal is the deified palace, she becomes the patron goddess of the king, his dynasty and family. At the end of the 3rd millennium in a new development her name becomes also a title for other goddesses (often Inanna/Ištar). After that it is hard to distinguish whether dNin-e 2-gal is a title of a different deity or if she still is worshipped as the deity "lady of the palace" herself, maybe with added new attributes. Aspects And AttributesProtection: for the king/his family/his dynasty, sometimes also for high officials or private persons. Fertility: because of the connection with Inanna in the sacred marriage; in the 1st millennium there are indications of a function as a midwife. War: with the king, possibly as another aspect of her protective function or an assimilation of the war aspect of Inanna. She is named together with warlike Inanna figures like Annunītum in Mari or the warlike Aštarte in Ugarit. Justice: with the king, probably resulting from a connection to Nungal or Inanna, who sometimes is also called a judge (i.e. Inanna and Iddindagan A) Healing: possibly within the framework of her protective aspect: healing powers to assure good health for the king (connection to Bau in the 1st millennium). Underworld: protection for deceased kings and ancestors (UR III ki-a-nag and in Ugarit) The pantheon of Ninegal/Bēlet-ekallim- Ninegal belongs to the circle of Inanna

- She belongs to the circle of Ninurta (mostly in northern Babylonia, where she appears next to Uraš)

- She is the centre of the palace pantheon and was worhsipped along with the protective gods of the kings.

Examples of palace deities: - Inanna of the palace (Ur III cities and Mari)

- Ḫebat of the palace (Emar)

- Išḫara of the palace (Emar)

- Sin and Šamaš of the palace (Emar)

Epiphets of Ninegal/Bēlet-ekallimnin-gidru (PA) - "Lady Of The Sceptre" [Gudea Iscription] nin-gal - "The Great Lady" [OB Inscription] na-ri-maḫ - "The Noble Adviser" [OB Inscription] dumu-gal-dEN.ZU - "The Great Daughter Of Sin" [OB Inscription] sukkal-nin - vizier [OB Syllabar] [be-el]-ti uruqat2-naki - "The Lady Of Qatna" [Inventory I Qatna] be-let um-ma-na-a-ti3 - "The Lady Of The Troops" (EMESAL: dgašan-e2-gal-la mu-lu ama-eren2-na) gašan e2-i-bi2 da-nu-um - "The Lady Of The Eibianum" [1st millennium literature/Dilbat] >>>Link |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 17, 2014 14:14:35 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 19, 2014 9:41:36 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 20, 2014 10:35:50 GMT -5

The article The Moon as seen by the Babylonians by Marten Stol published in Natural Phenomena, Their Meaning, Depiction and Description

in the Ancient Near East is a very interesting one. Starts at page 253 --->link |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 21, 2014 6:14:51 GMT -5

Detailed article ( Mythological Foundations of Nature) about the Mesopotamian cosmogony by F.Wiggermann from: Natural Phenomena, Their Meaning, Depiction and Description

in the Ancient Near EastStarts at page 287 .... No machine metaphor in Mesopotamia, but a history of gods; yet, in trying to understand nature, there is one metaphor we share with the ancients. It is the mathematical metaphor: all events belong to a series that must have a first member, a beginning, an unmoved mover . In third millennium philosophy this is Ocean, Nammu, distinguished from what follows by producing it asexually. What she produces is undivided Heaven-Earth, An-ki, and from then on production is in male-female pairs. Inside, Earth grows (Enki and Ninki) and produces a mound, Duku. Finally Ether, Enlil, and Mountains, Ninḫursagak, separate Heaven from Earth. Ether produces the moon, Nanna, the moon produces the sun, Utu, and the planet Venus, Inanna; the sky god, the offspring of sky, An, produces wind, Iškur, and (together with Ocean) Enkig, who remains a cosmic riddle. The universe is founded, but far from finished. Numberless minor entities are born from the great gods, but most of the work is done by hand: the great gods led by Enlil finish the universe and finally create man to take care of them. Natural phenomena, gods and their activities, are subordinated to just rule: Enlil and An. ... read the whole article here --->link |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Sept 10, 2014 16:38:47 GMT -5

From: The Religious Iconography of Cappadocian Glyptic in the Assyrian Colony Period and its Significance in the Hittite New KingdomBy Grace Kate-Sue WhitelinkPage 71

Sumerian Pantheons The pantheons of the different geographical or occupational units of Sumer have been summarized by Thorkild Jacobsen. Each city in Sumeria had a city-god, but the pantheons can be grouped as the "marshland," "herder," "shepherd," "orchard," and "farmer," patheons. The majority deities in these groupings are mostly the same, but family relationships vary, and the minor deities differ. Pantheon of the southern marsh Enki is prominent in this pantheon, and so most of the major deities appear as his children; whereas in the herder´s pantheon, the same deities are the children of Nanna.

|

| Enlil/Nammu (his housekeeper) |

|

|

| Enki/Ninhursaga (wife also known as Damgalnunna)

|

|

| Ereshkigal

| Inanna | Dumuzi

| Asalluhe

| Nanshe

|

|

|

|

| Ninmar |

In this pantheon, the deity Nanna(Sin) is the father of Ishkur, Inanna, Utu, Ereshkigal, etc. The character Dumuzi is a human sheepherder, and not Inanna´s brother as in the marshland pantheon.

|

| Enlil/(wife)Ninlil |

|

|

|

| Nanna(Sin)/(wife)Ningal |

|

| | Ereshkigal | Inanna | Utu | Ishkur | Ninhar |

|

| Shakan |

|

|

This pantheon contained deities associated with the nether world of the dead. Damu appears here as the greatgrandson of Enlil or Ereshkigal. Enlil/Ninlil or Ereshkigal

| Ningasu/Ningirda(daughter of Enki)

| Ningishzida/Ninazimua

| Damu

|

Ninurta was a deity with a double nature--that of the "farmer of Enlil" and god of the south wind, and hence a storm god of pestilence. This war-like side of Ninurta was symbolized by the beast Imdugud a lionheaded or double-headed eagle. A myth concerning Ninurta reports his adventures in slaying a dragon/serpent.

| An |

|

| Enlil/(Wife)Ninlil |

|

| Ninurta/(Wife)Bau | Nergal/(Wife)Ereshkigal |

In general, in all the Sumerian pantheons Enlil was a storm god and king of heaven. As king of heavens he made plans, but it was Enki who put the plans into action. Enki was the god of water, both fresh water of lakes, rivers, canals, and marshes, but also of rain. Enki´s title was "lord of the earth." He was the god of ablution because of the cleansing power of water. It is the god Enlil who brought "evil" to justice. i.e Enki´s son Asalluhe who saw evil, reported to Enki who sent his messenger (the incantation priest) with a human complainant "to the law court of the divine judge Utu (Shamash), the sun god, who hears the complaint and gives judgement in an assembly of gods. Enki undertook the responsibility for execution of the judgement. Enki was also the holder of the mes. The 100 mes were divine decrees fundamental to civilization. Each of the 100 elements required a me to originate it and keep it going. The elements included godship, kingship, sheperdship, sribeship, wisdom, peace, sexual intercourse; and the crafts of leather, basket weaving, metalworking. Enki´s wife was Damgalnunna another name for Ninhursag. In the marshland pantheons he was considered the father of Inanna, Dumuzi, Asalluhe, Ereshkigal, and Nanshe. Utu was the god of the sun as well as justice and equity. In the herder´s pantheon he was the son of the moon god Nanna, and the sister ( sic) of Ereshkigal and Inanna. Dumuzi was considered the son of son of (sic) Enki in the Marshland pantheon, a human son of Ninsun in the cowherd pantheon, and son of Duttur, goddess of the Ewe in the sheperd´s pantheon. Dumuzi is the "dying" god. In the myth of Inanna´s descent into the Netherworld, Inanna chooses her husband Dumuzi to replace her in the underworld when she returns to earth. In the orchard-man´s pantheon Damu is a related figure. Damu is a vegetation god. His name means `the Child´ and he was a disappearing god. His cult "centered in rites of lamentation and search for the god, who had lain under the bark of his nurse, the cedar tree, and had disappeared. The search ended in finding the god, who reappeared out of the river. Part of the cult in the third Dynasty of Ur and the early kings of the following dynasty of Isin, was the recognition of all dead kings as deified and as incarnations of Damu. "The cult of Damu influenced and in time blended with the very similar cult of Dumuzi the shepherd. There were several weather-gods; Ninurta, Asalluhe, and Ishkur. Ninurta was considered the son of Enlil and thus could be considered at least a half-brother to Ennki (sic) (they had different mothers). Ninurta was the farmer´s version of god of the thunder and rainstorms of the spring. It was the early rains that melted the snow in the mountains and swelled the rivers, and so he was also the power of floods. Because of the violent nature of spring rains and floods, he also had a violent, war-like side. | Ninurta´s earliest name was Imdugud, which means ´Rain-Cloud.´ and his earliest form was that of the thundercloud, envisaged as an enormous black bird floating on outstretched wings, roaring it´s thunder cry from a lion´s head. With the growing tendency toward anthropomorphism the old form and name were gradually disassociated from the god as merely his emblem; enmity toward the older, inacceptable shape eventually made it evil, an ancient enemy of the god, a development culminating in the Akkadian myth about it (Imdugud) as Anzu. |

This Akkadian myth concerns the slaying of the dragon Anzu. Ninurta was also considered as the chtonic aspects of the sun-god, and as a god of fertility.

Ninurta was especially important in Assyria.

Ishkur in the shepherd´s pantheon was also a god of rain and thunderstorms in the spring. He was equated with Ninhar of the cowherder´s pantheon and was thus considered to be the son of Nanna, the moon god. His symbol was the lightning fork. As a god of rain and thunder he corresponds in the herdsman´s pantheon to Asalluhe in the mashman´s and has the epiphet, `men-drenching`in common with him. In the farmer´s pantheon his counterpart is Ninurta. Ishkur´s wife was the goddess Shala. Since Asalluhe was Enki´s son, when Ishkur and Ninurta are equated with Asalluhe they can be concidered sons of Enki.

Asalluhe´s name `Man-Drenching Asal` indicates that he was the god of thundershowers. In the incantations, it is regularily Asalluhe who first observes and calls Enki´s attention to existing evils. He was later identified with Marduk of Babylon.

Nergal was the ruler of the nether world and spouse of it´s queen Ereshkigal. "This may not have been original with the god, since other gods are mentioned as Ereshkigal´s spouse in the older tradition, and since an Akkadian myth explicitly tells how he came to occupy that exalted position." In the farmer´s pantheon he may originally have been a tree god under his other name Meslamtaea. Nergal was similar to Ninurta and was considered to also have war-like aspects of the sun-god.

Ninhursaga in the northern ass herder´s pantheon was the spouse of Shulpae. Frankfort says that Nergal was also known by that name. As the spouse of Shulpae she was the mother of sons Mululil and Ashshirgi and a daughter Egime. "Mululil appears to have been a dying god, comparable with Dumuzi and Damu." In the marshland pantheon she was the spouse of Enki.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Sept 22, 2014 20:29:07 GMT -5

Sheshki:

Thanks very much for this post! As White mentions, her view of the regional pantheons of ancient Sumer is heavily indebted to the classic formulations on this subject published by Thorkild Jacobsen, perhaps best seen in his The Treasures of the Darkness. Her subsequent comments about the individual gods seem generally on the mark to me. It's easy to forget that Asalluhi was a weather god, I believe he had particular relevance to rain clouds, this is often overshadowed by his role in the incantation literature. To say that Ninurta was certainly the Imdugud at some early point in the mythology seems to overstate our understanding in my opinion. Further, White should refrain from referring to Henri Frankfort about the character of Nergal or his supposed identification with Shulpae, there are far more recent studies which examine Nergal. Beyond that, this is an excellent note on the pantheons of Sumer and an important reminder to our readership: there were numerous different conceptions of pantheon, and variations were not only regional but could vary from one urban center to another, and again between priestly, royal and scribal traditions.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Apr 6, 2015 9:15:42 GMT -5

NANAIA Nanaia (Sumerian     , DNA.NA.A, Babylonian DNA.NA.A.A; also transcribed as Nanâ, Nanãy or Nanãya; in Greek: Nαναια or Νανα; Aramaic: ננױננאױ) is the canonical name for a goddess worshipped by the Sumerians and Akkadians, a deity who personified "voluptuousness and sensuality". Her cult was large and was spread as far as Syria and Iran. She later became syncretised with the Babylonian Tashmetum. 1The following is a sum-up of the article about Nanaia from RIA9/146, for more details go there. -Firstborn of Anu -two known daughters, Kanisura and Gazbaba -"Hand of Nanaia of Uruk", a desease that only affects woman -Cultic places of Nanaia: main cult centre is Uruk, where she can have the names "Queen of Uruk" or "Lady of Uruk", Ur - "Nanaia in the palace", Kiš, Sippar, Borsippa, a sanctuary between Babylon and Borsippa, a shrine in the Esagila in Babylon and others -consort of Nabu -later conflated with Ištar -Temple in Uruk is E 2-ḫi-li-an-na, Borsippa E 2-ur 5-ša 3-ba, E 2-me-ur 4-ur 4 in Uruk and Babylon, E 2-ḫi-li-diri-ga in Uruk, E 2-ša 3-hul 2-la in Uruk and Kazallu, E 2-tur 3-kalam-ma (for dInanna and dNa-na-a-a) in Babylon, a temple to dInanna and dNa-na-a in Isin -cultic activities: according to the Uruk calendar each month on the 7th day the lament A-še-er-gim e 3-ta was sung, on the 14th day of the 8th month a lament for the lady of Uruk and the song Uru ḫul-am 3-ke 4, on the 3rd day an Eršemma song ect. -according to a letter "after 1635 years Assurbanipal brought her statue back from Elam...where she was brought by Kutir-Naḫḫunte II of Elam" 2Sacred marriages of Nabu took place in both Babylonia and Assyria. The Babylonian ceremony began on the 2nd day of Ajaru, when Nabu and Nanaia entered their bedroom in a nocturnal procession. From here the god went out into the garden on the 6th, and on the 7th reached the Emeurur,"temple which gathers the divine ordinances" in the area of the Eanna. Here Nabu received the kingship of Anu, perhaps as a result of marriage with his daughter. 3Early Old Babylonian royal inscription from Larsa ( P448427) | {d}na-na-a | For Nanaia, | | nin hi-li še-er-ka-an di | lady adorned with allure, | | nam-sa6-ga-ni gal diri | whose beauty is surpassingly great, | | dumu zi-le an gal-la | the good daughter of great An, | | nin-a-ne-ne-er | their mistress - | | ku-du-ur-ma-bu-uk | Kudur-mabuk, | | ad-da e-mu-ut-ba-la | father of Emutbala | | dumu si-im-ti-ši-il-ha-ak | and son of Simti-šilḫak, | | u3 ri-im-{d}suen dumu-ni | also Rīm-Sîn his son, | | nun ni2-tuku nibru{ki} | the prince who reveres Nippur, | | u2-a uri5{ki}-ma | provider of Ur, | | lugal larsa{ki}-ma | king of Larsa | | lugal ki-en-gi ki-uri-ke4 | and king of Sumer and Akkad, | | e2-sza3-hul2-la | the Temple That Gladdens the Heart, | | ki-tuš ki-ag2-ga2-ni | her beloved residence, | | nam-ti-la-ne-ne-še3 | for their lives | | mu-na-du3-uš | they built for her. | | sag-bi mu-ni-in-il2-iš | Its top they raised up high there | | hur-sag-gin7 bi2-in-mu2-uš | and like a mountain range they made it grow. | | ur5-sze3-am3 | For this, | | {d}na-na-a | may Nanaia, | | nin {d}lamma-ke4 | queen of the female guardian angels, | | u3-mu-ne-hul2 | rejoice at them, | | nam-lugal ša3 hul2-la | and a kingship of happiness, | | bala nam-sa6-ga | a reign of goodness, | {d}lamma šu-a gi4-gi4

| and a responsive(?) guardian angel | | ki an {d}inanna-ta | from An and Inanna | | al hu-mu-un-ne-de3-be2 | may she request from them. |

That the goddess's spiritual domain and her imagery found even greater ramifications in subsequent centuries, is now documented by recent archaeo- logical evidence uncovered in Soviet Central Asia. It now appears that the worship of NanA eventually spread beyond the Near East and the Iranian plateau, to Bactria and Transoxiana where the goddess played a leading role in the local pantheons of the east Iranian world...Nana's cult and manifestations prevailed in Transoxiana because the Mesopotamian goddess was there equated with an equally powerful Iranian deity. My Lady, Sin, Inanna, born of ..., similarly (?) / I am the same (?) Wise daughter of Sin, beloved sister of Samas, I am powerful in Borsippa, I am a hierodule in Uruk, I have heavy breasts in Daduni, I have a beard in Babylon, still I am Nana. Ur, Ur, temple of the great gods, similarly (?). They call me the Daughter of Ur, the Queen of Ur, the daughter of princely Sin, she who goes around and enters every house, holy one who holds the ordinances; she takes away the young man in his prime, she removes the young girl from her bedchamber-still I am Nana In the Third Dynasty of Ur the goddess appeared to combine the qualities of Inanna with those of Ištar. In an Old Babylonian hymn Nana's father An, is said to have elevated her to the position of a supreme goddess, which presumably symbolized the ratification of her superlative qualities. The Sumero-Akkadian hymn quoted above, gives a description of the goddess under her different names, in various cities and temples, and the names of her different husbands in the Late Assyrian period. Nana's attributes, noted in that hymn, were those of Ištar, daughter of the moon-god Sin and sister of the sun-god Šamaš. Her manifestations ranged from a bearded Ištar in Babylon, to a goddess with heavy breasts in Daduni. 4Nanaya The goddess Nanaya, who seems to have shared some of the sexual aspects of Inana, was worshipped together with her daughter Kanisura (Akkadian Usur-amassa) and Inana of Uruk in a sort of trinity of goddesses at Uruk, and later at Kis, during the Old Babylonian Period. Later Nanaya's name was used in cultic texts to denote little more than another aspect of Inana/Istar. 51 Wikipedia

2 RIA9/146 3 RIA9/22 4 NANA, THE SUMERO-AKKADIAN GODDESS OF TRANSOXIANA by G. AZARPAY 5 Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, Black and Green Sumero-Akkadian Hymn of Nanâ by Erica Reiner |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on May 10, 2015 11:42:13 GMT -5

interesting object from the Diyala region link |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on May 10, 2015 12:24:52 GMT -5

From J. Hayes A Manual of Sumerian Grammar and Texts

Inanna She was the Sumerian goddess of love and fertility, of the morning and evening star,

and to some degree of war; she had other sides as well. She may have absorbed some of the

attributes of originally independent deities. Later equated with the Akkadian Ishtar, she was the

most important goddess in the Mesopotamian pantheon. Because of her fiery temperament and

the manifold aspects of her personality, she is perhaps the most interesting of all Mesopotamian

deities. Mesopotamian mythology was rather inconsistent about her ancestry; she was usually

described as the daughter of An, but sometimes as the daughter of Nanna.

She was worshipped in many cities, but especially in Uruk, where she was the tutelary goddess.

Her principal temple complex at Uruk was the E2-an-na, "House of the sky/heaven,

which occurs in Text 9b.

The reading of her name is much disputed; it is variously transliterated as Inana, Inanna,

Innin, and Ninni. It is usually interpreted as nin.an.a(k), "Lady of the sky/heaven". This is how

the Akkadian scribes understood her name. Jacobsen thinks that Inanna was originally the

"numen of the communal storehouse for dates". He says that the AN-component of her name

meant "date-clusters": "Her name ... would appear to have meant originally 'The lady of the

date-clusters"' (1970 [I9571 376 n.32). Later, her name was re-interpreted as "Lady of the sky/

heaven".

The sign for her name may represent a bundle of reeds.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on May 16, 2015 7:45:11 GMT -5

Sheshki: A nice commment from Hayes, I am particularly interested in what he says about the name of Inanna. The analysis "nin.an.a(k)" lady+heaven+genitive (of) certainly fits with that we know of the religion of Inanna, especially as evident in the myth "Inanna and An". I am interesting in Hayes remark "this is how the Akkadian scribes understood her name" , here he probably refers to a lexical list somewhere, such list is probably discussed in the series MSL (materials for a Sumerian lexicon) - in this series scholars isolate and discuss the bilingual and lexical material which sheds light on the Sumerian language largely with the help of Akkadian scribal efforts. Unfortunately we don't know which lexical text Hayes was referring to, but yes, that is the means by which much has been figured out.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jun 15, 2015 15:38:53 GMT -5

from RIA10/302

Gods in the Sumerian temple hymns

wisdom and art of writing:

Enki - Eridu

great gods and local circles:

Enlil- Nippur

Ninlil, Nuska, Ninurta, Šuzianna - Nippur

Ninb-ursaga - Keš

Nanna - Ur

Šulgi - Ur

Asarlubi - Kuara

Ningubalag - Kiabrig

Nanna - Gaeš

Utu - Larsa

Ninazu - Enegi

Ningišzida - Gišbanda

Inanna - Uruk

Dumuzi - Badtibira

Ninšuhur - Akkil

Ningirima - Murum

following the Tigris upstream:

Ningirsu - Lagaš

Bawu - Eriku

Nanše - Nigin

NinMAR.KI - Guabba

Dumuzi-abzu - Kinirša

Šara - Umma

Inanna - Zabalam

Iškur - Karkar

[ ... l .

Ninhursaga - Adab

Middle-Babylonia:

Ninisina - Isin

Numušda - Kazallu

Lugalmarada - Marada

Ištamn - Der

Northern Babylonia up to Akkade:

Ninazu - Ešnunna

Zababa - Kiš

Nergal - Gudua

Nanna - Urum

Utu - Sippar

Ninbursaga - HI.ZA

Inanna - Ulmaš (Akkade)

Ilaba - Akkade

Wisdom and art of writing

Nisaba - Ereš

gods in the Codex of Hammurabi, Prologue

Great Gods:

Enlil - Nippur

Ea - Eridu

Marduk - BabyIon

Sin - Ur

Šamaš - Sippar und Larsa

(Anu und) Ištar - Uruk

Ninisina - Isin

Zababa und Ištar - Kiš und Hursagkalama

Erra - Gudua

Tutu - Borsippa

Uraš - Dilbat

Mama - Keš

Tigris upstream:

(Ningirsu) - Lagaš und Girsu

Ištar - Zabalam

Adad - Karkar

(Ninmah) - Adab

(Nergal) - Maškanšapir

Ea und Damgalnunna - Malgium

middle Euphrates:

Dagan - Mari und Tuttul

further upstream

Tispak - Esnunna

Ištar - Akkade

"Genius" (Aššur) - Assur

Ištar - Ninive

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 14, 2015 16:37:09 GMT -5

Dream God(s)

From RIA7/ 331

Mamu(d) dMa-mu/mu; in PBS 112 112:

48: dMa-mu (collated». The Sum. noun

"dream" used of the deity of dreams. In An

= Anum III 137: dMa_mu[šu].ut.tum = du=

mu.munus dUtu.ke4 "Mamudream

daughter of Samaš" her sex and parentage

are given, and the latter seems to be confirmed

by two OB documents which begin

their witness lists with "Samaš, Aja, Mamu"

However, the female sex in

An = Anum is apparently conditioned by

the gender of the Akk. noun šuttu. Elsewhere

Mamu is male: in Akk. prayers and at Balawat

where Aššurnasirapli built a temple for him.

Other names of the dream god are Sisig (Sum.) and Ziqiqu

(Akk.), also AN-za/zag-ga(-ra) (used in

both languages).

A.L.Oppenheim, Dreams (1956) 232.ff.

W.G. Lambert

From: Mesopotamian Conceptions of Dreams and Dream Rituals (1998)

by Sally A.Butler

"For some reason the Mesopotamians also developed a concept of a Dream God

(in fact, the sources provide us with four main names: Mamu; Sisig; Za/iqiqu; and Anzagar),

yet his functions are ill-defined, and he is rarely mentioned in the technical dream literature."

dMA.MÚ

MA.MÚ mainly occures in Sumerian texts. There are various references to dMA.MÚ which place the god within the retinue of Shamash.

Ashurnasirpal II erected a temple to him at Bawalat (ancient Imgur Enlil)...

dSIG.SIG

We have noted already that the God List an=Anum attributed a brother

to a feminine Mamu: CT24, pl.31, col.IV line 85:

dSI.SI.IG | DUMU dUTU.KE4

Sisig (is) a son of Shamash

The late version, SpTU 3, No.107, presents this line, with a gloss,

in col.III line 137:

dSÌGZi-qi-quSÌG | DUMU dUTU.KE4

The correlation of two names of the Mesopotamian Dream God,

the Sumerian Sisig ("the one who constantly blows"or "the winds")

and the Akkadian Zaqiqu ("a breeze", see on) is reinforced by ZI, line 1,

where its Akkadian manuscript has Zi-qi-qu,

but its two Sumerian texts have SI.SI.IG and SIG.SIG - all without

the determinative. All these passages invalidate the generally accepted,

yet unproven, identification of Anzagar with Zaqiqu. These lines are the only references that

the writer has found, and only ZI suggests that he was a Dream God.

(References cited here under dZaqiqu/Ziqiqu offer more examples of the

equation with the logogram SI.SI.IG, etc., also with LÍL.LÁ.)

dZaqiqu/dZiqiqu

The Akkadian name of the Dream God was Zaqiqu, also written Ziqiqu, which is not known in logographic form.

zaqiqu is a derivative of the verbal root zig or, possibly, from zqq. The word has

been given many nuances by modern translators, which are briefly mentioned below.

Nuances of zaqiqu

a). Wind And Nothingness

The associated verb, zaqu, means "to blow", and zaqiqu is equated in lexical texts

with words denoting wind, storms, etc.

zaqiqu usually refers to a mild breeze, but may imply a storm...

CAD Z, p.60b stated that zaqiqu only refers to a wind in lexical texts and in a few passages

concerning the north wind. It preferred meaning "ghost" from equation with with LÍL.LÁ,

as in the names of certain demons. Accordingly, expressions used in lamentations, literary texts, and royal

inscriptions to portray the total destruction of a site such as ana zaqiqi manu, "to count as wind",

and ana zaqiqu taru, "to turn into wind", are rendered as "to count as ghosts" and "to turn into a haunted place",

respectively [CAD Z, p. 59].

In some passages zaqiqu expresses "nothingness": e.g., the Verse Account, col. I line 20:

20'). ib-ta-ni za-qi-qi

He (Nabonidus) created wind (i.e., none of his achievements lasted or were of any value).

b). A Wind Demon Or A Type Of Ghost

The verb zaqu describes the swift movements of various demons whilst attacking mankind[CAD Z, pp. 64-65].

The zaqiqu winds developed into a category of Mesopotamian demons, which was characterized by

forms of našarbutu, "to rush forth": e.g., CT 16, pl. 15, col. V lines 37-40:

37). ù munus.nu.meš ù nita.nu.meš

38). ul zi-ka-ru šu-nu ul sin-niš-a-ti šú-nu

39). e.ne.ne.ne líl.lá bú.bú.meš

40). šú-nu za-qí-qu mut-taš-rab-bi-tu-ti šú-nu

37-40 They are neither men nor woman, they are the zaqiqus, who constantly rush along.

OrNS 39 [1970], pls. 54-55 (after p. 464), col I lines 4-10 reveals that

zaqiqu-demons were envisaged as being similar to ghosts, and dwelling in the Underworld/grave:

4). líl.lá.e.ne hul.a.meš urugal.la.ta

5). im.ta.è.a.meš

6). za-qí-qu lem-nu-ti iš-tu qab-rì it-ta-su-ni

7). ki.sì.ga.a.dé.a.meš (an) urugal.la.ta

8). im.ta.è.a.meš

9). a-na ka-sa-ap ki-is-pi u na-aq mé-e

10). iš-tu qab-rì MIN (i.e., it-ta-su-ni)

4-6 The evil zaqiqu(-demons) come out from the grave.

7-10 They come out from the grave for the presentation(s) of funerary offerings

and libation(s) of water.

The idea of the zaqiqu-demons residing in the Underworld is reinforced by the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Enkidu descended to the Underworld to retrieve the pukku that Gilgamesh had dropped,

but was detained because he disobeyed all the instructions which would have allowed him to return

to the world of men. Ea tells Gilgamesh how to talk to Enkidu after this has happened - Tablet 12,

lines 83-84, and the Sumerian version, Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld, lines 242-243 (see A. Shaffer[1963]):

242). ab.làl.kur.ra gál im.ma.an.tag4

83). lu-man tak-ka-ap KI-tì ip-te-e-ma

243). si.si.ig.ni.ta šubur.a.ni kur.ta mu.ni.in.e11.dè

84). ú-tuk-ku šá dEn-ki-dù ki-i za-qí-qí ul-tú KI-tì it-ta5-sa-a

242, 83 Scarcely had he (Gilgamesh) opened a hole in the earth/Underworld,

243, 84 The utukku of Enkidu, his servant, came out from the Underworld like a zaqiqu.

(utukku normally refers to another type of demon, but in this passage it seems to mean "ghost".)

c). Human Soul

When zaqiqu is used with amilutu, "mankind", or nišu, "people", it appears to mean "human soul" (see T. Jacobsen [1989], pp. 274-275 on this nuance of líl; and DB, p235, for an altermative explanation):...

The Dream God dZa/iqiqu

The only evidence we have that Zaqiqu was a Dream God is that the Dreambook was called (d)Za/iqiqu from the incipit of its first incantation (ZI). (Zaqiqu is not always prefixed with the divine determinative, possibly indicating his minor or demonic status;...)

C.J. Gadd [1948, p. 74] believed that ZI was a brief introductory myth, which described Zaqiqu as the first to interpret dreams and residing in Agade. However, ZI mentions that Zaqiqu had been sent to Agade, whereupon he caused someone to dream (the manuscripts vary as to the category), and that a third person interpreted them. E.I. Gordon [1960, pp 129-130, n57] suggests that an allusion may have been made to Naram-Sin as "the luckless ruler of Agade"

ND 4368 (Iraq 18 [1956], pl. 25) provides us with the only reference to the deity Zaqiqu outside the dream literature and lexical texts. J.V. Kinnier Wilson [1957] stated that this fragmentary and difficult tablet formed part of a companion medical series to the diagnostic omen series SA.GIG; both belonging to the löore of the exorcist. The listed deseases are termed 'Hands' of various demons who, in turn, are designated as the šedu-demons and agents of the divine triad....

CAD Z, p.59, § 1 2' (based on DB, p.235) presents passges in which zaqiqu "refers to a specific manifestation of the deity", which may or may not reply to human inquiries. AHw 3, p. 1530b, §4a placed the same citations under "Traum(gott)". In the passage below , the basic problem is wether zaqiqu is a human ritual expert or a spiritual entity. The writer inclines towards the former.

The protagonist of Ludlul bel nemeqi unsuccessfully sought omens and remissions of his suffering on Tab.2, lines 6-9. including:

8). za-qi-qu a-bal-ma ul ú-pat-ti uz-ni

I appealed to a zaqiqu but he did not enlighten me (lit., did not open my ear).

P.C. Couprie [1960, p. 186] stated that here zaqiqu had to be a ritual expert, paralleling the other pracvtioners, and certainly one would expect a reference to a human, rather than to a spiritual being or a "specific avenue of communication with the god" [DB p.235]. This zaqiqu is distinguished from the ša'ilu (often translated as "dream interpreter") of line 7.

....

....DB p. 235 stated that this zaqiqu was not a Dream (God), against F.R. Kraus [1936, p.88], but was the insubstantial carrier of the divine message. Still, the description of the Dream God Anzagar as "the medium of Nannaru" (i.e., of Sin) on SDR, line 32, is brought to mind.

M. Streck [VAB 7, p.347, n. 11] proposed another alternative; this zaqiqu was a type of Wahrsagepriester or baru, who was especially concerned with incantations against ghosts. It is possible that a ritual expert uttered an inspired speech in a temple while standing in front of a statue of Nabu.

...

In conclusion, it seems that zaqiqu occasionally denoted a professional, who may have prophesied and/or supervised the incubation process (remembering the bit zaqiqi in the successive dream incubations on the Epic of Gilgamesh, Tab.4, page 225).

dAN.ZA.GÀR/AN.ZAG.GAR.RA

In earlier studies this name was written as dZA.GÀR yet, recently, perhaps since [DB], the custom has been to write it AN.ZA.GÀR. T.Jakobsen rendered it as Ìl-za-kár,

designating it as early loan from Proto-Akkadian.

*AN.ZA.GÀR appears in rituals to obtain a pleasant dream as well as in incantations connecting him to demons, ghosts, and the Underworld.

|

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Aug 17, 2015 5:07:14 GMT -5

Sheshki - thank you for looking into the dream god, I think you are on the right path so far as research goes, these are some of the very few descriptions of these deities in Assyriological literature. As I mentioned to you, should you want to introduce further material to enenuru, there are a few German treatments of the drem gods which have eluded us for some time now..  |

|

|

|

Post by hukkana on Oct 21, 2015 15:11:22 GMT -5

So I was wondering, would the seemingly very obscure Eblaitic Gods qualify for inclusion in this list ? I'm talking about deities like Agu, Aniru and the like ?

Some of these Gods have a Syrian origin so I was wondering if that would be covered as well.

|

|

|

|

Post by hukkana on Oct 28, 2015 8:33:34 GMT -5

Well, after talking with Sheshki I'll add the following: Gods of EblaThe Eblaite Gods stem from various sources so it includes moth Sumerian and Syriac deities. This is a short list, as I've found refferences to many more Gods reffered to anonymously but finding the specific God lists and offering lists is very hard. Kura

The Chief God of the city of Ebla, venerated in the so called Red Temple. His Temple has the "House of the Dead" mausoleum attached to it. During the Greater Šaba'tum ritual he was invoked as "Gutim", "the Former one". In the Third Month of the Eblaitic cultic calendar, silver was given for the renewal of the silver head of his statue, and then for the renewal of the bracelets of said statue in a later month. He also plays a part in the very lengthy Royal Marriage cermeony/procession which consisted of rituals which I summed up on one of my projects thusly: "The ceremonies of the royal wedding begin with the Bride-Queen sacrificing one sheep to the Sun and one to the royal ancestor of the dynasty. On the first day the bride cannot enter the city. Gifts of her "father's house" are sent to the Gods and Temple of Kura on the second, entering through the Gate of Kura at the Nort-Nort-East Side of the city. In the Temple of Kura the Bride offers to Kura, Barama, Išru and Išhara. On the fourth day, a procession follows in the direction of Nirar. The Gods Kura, Barama and Aniru are moved from their Temples, each on seperate carts drawn by oxen, while the King and Queen travel on carts pulled by mules. They are accompanied by the High Priest of Ebla and the Attendant of Kura. The procession goes on the road to Masad, Nirar, Lub, and passed into Irad, then to Uduḫudu, making offerings to the deified Kings, then go to Bir, where offerings are made to Išru, and then entering the city of Niap where offerings are given to the Gods Kamiš, Aʾaldu and Daiʾn. On the seventh day the procession enters Nenaš. The king and queen, together with the statues of Kura and Barama enter “the house of the death”/é ma-tim /bayt mawtim/. The King and Queen then "sit on the throne of their fathers by the Waters of Mašad, those of NIrar". The Mother-goddess Nintu “makes an announcement, and the announcement that Nintu makes is that there is a new god Kura, a new goddess Barama, a new king, a new queen." The subsequent rights at Nenaš take place in three seven day cycles, with offerings to Kura, Barama and the deified ancestors during each cycle. On returning to Ebla the "renewed" King offers to the deified ancestors and to Išḫara and at the Kura Temple, which rites takes a further two seven day cycles, the ceremony totalling six weeks. " During this ritual the deified ancestor Kings also receive regular offerings at certain points, see Archi's "Ritualisation". He is the husband of the Goddess Barama. BaramaWife of Kura, Chief Goddess of Ebla. AdarawanMountain God, Lord of the Eagles, God of Današ and Sutig. RašapGod of protection against plagues, with an origin in the Caanan, also venerated at Ugarit. AdammaConsort of Rašap, also worshipped among the Mittani. ŠanugaruGod of the New Moon, husband of Išhara . BalihaRiver Goddess/deified river. AšdabilGod also worshipped in Mittani, apparently a version of Aštabi, mentioned in The Song of Ullikummi as one of seventy gods defeated by Ullikummi. BaraduConsort of Ašdabil. HaburitumGoddess of the Khabur river. Hadabal

A god which seems to be derived from Hadad. A Princess of the royal house was chosen as Dam-Dingir/High Priestess/Spouse of the God and had a residence in his cult centre at Luban. He had festivals at Luban and Larugadu and a yearly procession that went through Mardum, Zidaik, Zarami, Ibsarík, Darib, Ibsuki, Aneik, then through Darib again into Gubazu and then into Ebla and then through Adatik, Arigu, Arzú, Ganat, Išdamugú, Šadadu, Daraum, Dubù tur, Arga, Nanabiš, Dubuki, Ùdurúm, Šè’àmu, Adubù, Zabu, Bùran, Sidamu, Darin, Ambar, Abaum, Gàru, Dušidu, Ùran, Abùdu, Arugú, Ikdar and Lu-teki. GananaGoddess associated with rituals of Kura and Barama, received a mašdabu pallium ever year. IdaDeity of the Palace. KamišPresumabely a version of the Moabite god Chemoš. KašaluA version of Kothar-(wa khasis ?) from Ugarit. IsatuPresumabely a Goddess of Fire. KabkabGod of the morning star. BelatuConsort of Dagon at Ebla. Hadda of HalabStorm God of Halab. HalabatuSpouse of Hadda of Halab. IšharaImportant Goddess, worshipped at Emar and among the Hittites. Šipiš Version of the Sug God, Guardian of Justice. UtuSun God. Utu.salSpuse of Utu. ŠamaganVersion of Šumugan. ZilašuGoddess of wine and honey. Wada'anuThe "divine spirit" god to consult in relation to the deceased. Sasa of GaramuSpouse of Wada'anu. Other Rarely Attested Gods:Gods: Nidakul of Luban A'aldu Agu Alu Aniru Daiʾn Gapadu Garainu Išru Lalitum Ninkardu Timut Goddesses Dabinatu - Spouse of Alu Guladu - Spouse of Agu Most of this information came from Archi's Ritualisation at Ebla, www.academia.edu/6637106/Ritualization_at_Eblaand Studies in the Ebla Pantheon, II www.jstor.org/stable/43078145?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contentsWhile I found mentions of other deities like the local version of Kothar in the publicaly viewable version of Handbuch der Orientalistik: Geschichte her Hethitischen Religion books.google.cz/books?id=-BsEXO8BVokC&pg=PA547&lpg=PA547&dq=%22Zuramu%22+Ishara&source=bl&ots=PGdyZpTJma&sig=PX8mpKOL4qxcOAxloPA0z8xGv24&hl=cs&sa=X&ved=0CB8Q6AEwAGoVChMI5r7hhuHTyAIV5v9yCh2i2A36#v=onepage&q=%22Zuramu%22%20Ishara&f=false |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Oct 28, 2015 15:47:52 GMT -5

From: CANE; Religion and Science; Theology, Priests, and Worship in Canaan and Ancient Israel; Pantheons p.2045

The oldest known Syro-Palestinian pantheon is that of Ebla (about 2450-2250). Its principal god is Dagan, "lord of the land" and "lord of the gods." One of the most popular West Semitic deities, Dagan was a major god in western Mesopotamia as well. In Old Babylonian texts from Mari he is referred to as the "judge of the gods" and the "god of the land." Texts from Emar (1300-1200) call him "lord of the cattle" and "lord of the seeds," implying that he was expected to provide fertility. Yet in the same texts Dagan figures as a warrior god: he is "lord of the military camp" and "lord of the quiver." The latter designations are similar to the earlier texts from Mari, where Dagan is said to go at the head of the royal army.

Only second in rank to Dagan in the Eblaite pantheon is Adda, elsewhere known as Addu, Adad, or Hadad. Several Adads were worshipped at Ebla, each related to a different city in the vicinity. Closely associated with the storm, Adad has both fierce and beneficial traits. He is the "thunderer" (Ramman...), pictured on plaques and seals as a warrior brandishing a shaft of lightning. In Ugaritic texts he is said to be the son of Dagan. Such was presumably the relationship between the two gods in Ebla as well. In the religion of Ugarit, the god Adda (usually called Baal) gained precedence over Dagan. His ascendency had apparently not yet been established by the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age.

The category of the "chthonic" deities, that is, gods associated with the earth and the underworld, is represented by at least three figures in Ebla: Rasap, Kamish, and Malik. Rasap, elsewhere known as Rushpan (Mari) or Rashap (Ugarit, Emar), is a god of war and pestilence. In the state cult of Ebla, various local Rasaps were provided with offerings. Kamish is probably the same Kammush, a variation of Nergal according to a Middle Assyrian copy of a god list. Since Nergal is a god of the underworld, Kamish also must have been regarded as such. In the Late Bronze and Iron ages, worship of Kamish was largely limited to the Transjordanian region. Malik - later Milku (Ugarit, Emar)...- occurs only as an element in perosnal names. He, too, was assimilated to Nergal in Mesopotamian texts.

From: CANE; History and Culture; Ebla: A Third-Millennium City-State in Ancient Syria; Palace Economy and the Role of the Temples p.1225

...Some of these gods had Semitic names, such as Dagan, Ishtar, and Hadda (´Ada), while the names of other gods were either of Hurrian (Ishkara and Ashtapi) or of an as yet linguistically unidentified language (Nidakul and Kura). The most important temple was certainly that of Kura, the tutelary god of the royal family, in association with Barama, a goddess attached to his cult. To make a vow before Kura (DU11.GA GABA dKU.RA) and to take an oath (NAM.KU5) in his temple were common procedures to validate state agreements or private deeds, such as dividing up an inheritance and donating real estate.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Oct 29, 2015 11:33:40 GMT -5

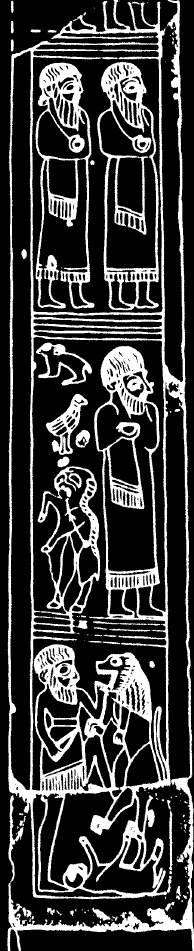

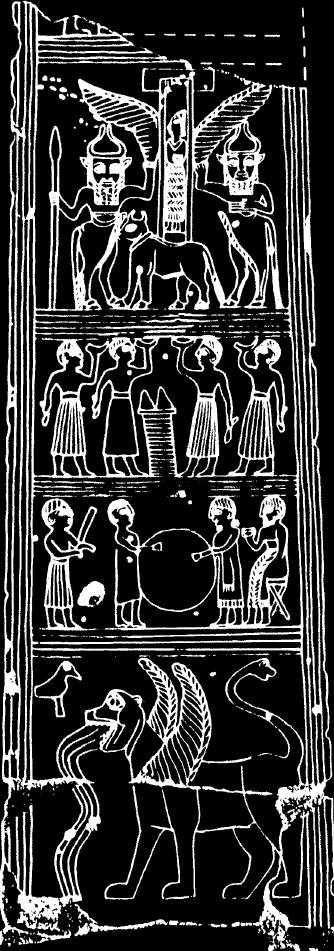

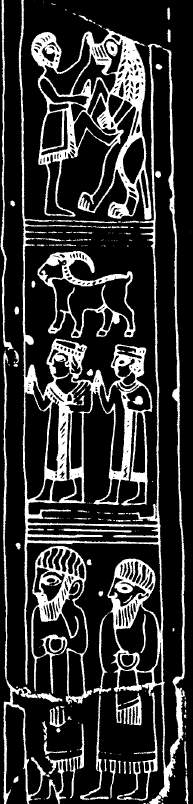

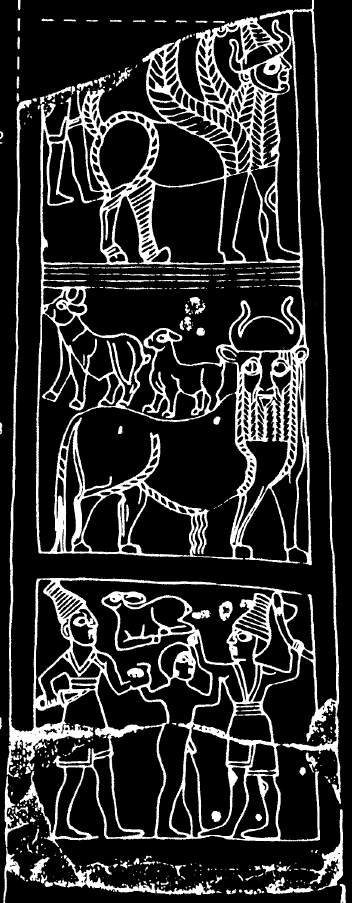

From: Cultic Activities in the Sacred Area of Ishtar at Ebla during the Old Syrian Period: The "Favissae" F.5327 and F.5238 by Nicolò Marchetti and Lorenzo Nigro The most significant document for the interpretation of the cultic activities is the Stele of Ishtar, erected near the doorway of a small shrine in the Square of the Temple D on the Acropolis and approximately contemporary with the favissae. Among the motifs represented on its sides , there are cup bearers (one next to a young ram, a dove and a hare) and, perhaps, two pristessess who are about to slaughter a goat. While the cup seems to be the collared bowl, of which many were found in the favissae, the animals are for the most part coincident with the specimens identified among the bones retrieved in the two sacred wells. On the back side of the stele, the motif of the two royal figures killing a naked prisoner next to a squatting lamb, is perhaps connected to the ritual that seems to be attested to in burial D.6274 in the Square of the Cisterns. Moreover, the possibility cannot be excluded that the libations in front of an altar are connected with the presence of several vessels in the favissae.     |

|

|

|

Post by us4-he2-gal2 on Oct 30, 2015 20:14:29 GMT -5

Hukkanu - This is such a fantastic comment on the Eblaite gods, personally, I know very little about these deities, but I will read this post over and reread it learn a thing or two. I am always astounded at your presenting the most obscure of details here on enenuru, obscurity which suits the board well.

Thanks for your additions as well Sheshki. So many curiosities on this stele, I notice an early instance of the human headed bull, and above that, another composite creature which I can't identify, may not be Mesopotamian hm.

|

|

|

|

Post by hukkana on Oct 31, 2015 15:26:30 GMT -5

I wouldn't exactly call the Eblaite pantheon obscure but thanks either way : P

Also updated the Kura entry with my summary of the Royal Wedding ritual.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Nov 17, 2015 19:53:42 GMT -5

From J. Hayes A Manual of Sumerian Grammar and Texts

Nin-Šubur

Ninšubur was a relatively minor deity, functioning as a kind of page or minister to

other gods. Sometimes Ninšubur appears to be masculine, at other times feminine. There may

originally have been two different deities, one masculine and one feminine. More likely there

was only one, who sometimes played a male ro1e and sometimes a female ro1e depending on

the deity being attended. In her female form, she is most well-known as the minister of Inanna,

playing a prominent ro1e in Inanna's Descent.

The word Šubur is presumably not Sumerian, but rather originally was the name of a people

living north of Sumer; Ninšubur was apparently a deity from this area. The word Šubur

(in both Sumerian and Akkadian forms) then came to be used as a rather vague geographical

term for the north and north-east of Mesopotamia, an area which was home to several different

ethnic groups. It is also possible that the original meaning of "Šubur" was "north" and then the

term was applied to a people living in the north.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Nov 17, 2015 19:58:19 GMT -5

From J. Hayes A Manual of Sumerian Grammar and Texts

Lamar

She was an intermediary or intercessory goddess. She appears on Ur III and Old Babylonian

seals introducing a worshipper to a higher god or goddess.

Although originating as one individual goddess, her protective aspect took

on a life of its own, and in time other gods and goddesses, and even private individuals, could

acquire their own personal Lamar aspect. The name Lamar becomes almost a generic word for

"protection". Thus, there occur PNs of the type Lugal-Lamar-gu10 ,king is my protection".

A thorough discussion of this goddess appears in the RLA ("Lamma/Lamassu"), by Daniel

Foxvog, Wolfgang Heimpel, and Anne Kilmer.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Nov 17, 2015 20:04:50 GMT -5

From J. Hayes A Manual of Sumerian Grammar and Texts

Nanše

This was the chief goddess of Lagaš. She was regularly consulted for the interpretation

of dreams. When Gudea, the ruler of Lagaš, had an odd dream in which a mysterious

figure appeared, it was Nanše to whom he turned for its explanation.

The cuneiform sign representing her name is basically the ab-sign

with an inscribed ku6-sign, fih . ku6 means "fish";

the sign is in origin the picture of a fish. This and other evidence indicates that Nanše

may originally have been some kind of fish-goddess. The same sign preceded by the determinative

for city (uru) and followed by the determinative for place (ki) stands for the city of

Sirara, one of the places where Nanše was especially worshipped.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 16, 2015 14:35:59 GMT -5

While reading in my new book "A Sumerian Chrestomathy" by K. Volk i discovered in text 9 a god i did not know much about so i did a little research. I found several short mentions in RIA, and since most of it was in german i will provide a summary.      d dNin-dar-a, before Gudea also written dNin-dar -spouse of Nanše, probably older brother of Hendursanga -agriculture and warfare related deity -cultic centre in Ki´esa, near Girsu -temples: E 2-lal 3-du in Ki´esa E 2-gud-du in Keš (tho i have also read that Ki´esa and Keš are mixed up sometimes because of similar writing, and the temple names given here look similar too if you see them in cuneiform. Also both temples are built by Gudea) E 2-lal 3-du/tum    E 2-gud-du    -in the 5th month of the calendar of Nigin (Nina) there was a festival celebrating the marriage of Nanše and Nindara, including a boat procession (Hendursanga hymn 28). There isn´t much known about Nindara, or to quote RIA9: Nindara bleibt für uns in seiner Gestalt und Funktion letzthin undeutlich. list of tablets on CDLI mentioning Nindara from: RIA9/154, 292, 338; RIA2/207, 280; RIA5/589; RIA4/324 text 9  1. {d}Nin-dar-a/ For Nindara 2. lugal uru 16/ the powerful king 3. lugal-a-ni/ his king 4. gu 3-de 2-a/ Gudea 5. ensi 2/ viceroy 6. lagaš {ki}-ke 4/ of Lagaš 7. e 2 gir 2-su {ki}-ka-ni/ his temple in Girsu 8. mu-na-du 3/ he built for him. |

|