|

|

Post by sheshki on Dec 19, 2015 15:46:31 GMT -5

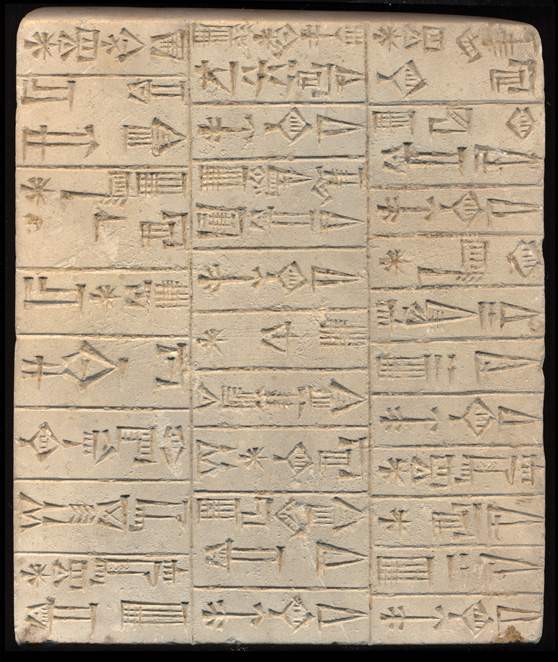

From J. Hayes A Manual of Sumerian Grammar and Texts

En-ki

He was the god of the subterranean waters and also the god of wisdom. He was a son

of Nammu. His main cult center was in Eridu, but he was worshipped throughout Mesopotamia.

In some god-lists he is ranked directly below An and Enlil.

His name apparently means "Lord of the earth", en.ki.(k). There are spellings which show

that this name is a genitive phrase, not a noun-noun compound. Why a god whose name means

"Lord of the earth" became associated with water is not entirely clear, although, as Jacobsen

has said, "from the earth also come the life-giving sweet waters, the water in wells, in springs,

in rivers" (1946:146). It has also been speculated that the element /ki/ appearing in this name is

a different word than the word /ki/ meaning "earth"; perhaps it is the same appearing in the

compound verb ki.. aga2.

The Sumerian god Enki was equated with the Akkadian god Ea (E2-a). The name of the

latter is of uncertain etymology; it does not inflect for case. In the bilingual lists from Ebla, the

Eblaite equivalent of Enki is written E2-u9 This would appear to be an inflected form of the

name, with the nominative case marker. It has been speculated that the Akkadian writing E2-a

and the Eblaite writing E2-u9 are phonetic spellings representing a Semitic form something like

/hayyu/, "The living one". This idea is explicitly developed by Cyrus Gordon (1987:19-20).

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 2, 2016 12:34:19 GMT -5

One of the ORACC projects, a list of Mesopotamian gods ->>> linkand a link to the other projects ->>> link |

|

|

|

Post by hukkana on Jan 2, 2016 14:04:25 GMT -5

I've known about that one for a while but they do seem to have some notable omissions, such as Aššur for example.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jan 10, 2016 14:26:30 GMT -5

from: City Administration of the Ancient Near East, Proceedings of the 53 e Recontre Assyriologique Internationale Vol.2; D.Katz; City Administration in Poetry,p77  |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Feb 23, 2016 4:36:28 GMT -5

From: Die königlichen Frauen der III. Dynastie von Ur, by Frauke Weiershäuser, p.47

A short quote concerning the cultic activities of Šulgi-simtī, the wife of Šulgi. (**i will add a translated summary later)

Neben den großen Göttern des Landes, Enlil, der die Königswürde

verlieh, und seiner Gemahlin Ninlil, dem Mondgott Nanna, Gott der

Reichshauptstadt Ur, und Inanna, der Göttin von Uruk, kümmerte sich Šulgi-simtī

intensiv um den Kult verschiedener Göttinnen, die sie aus ihrer Heimat

mitgebracht hatte. Hier sind zuerst Bēlat-Šuhnir und Bēlat-Deraban zu

nennen, welche in der Zeit nach Šulgi-simtī im Kult des Reiches von Ur kaum

noch eine Rolle spielten. Die Göttin Allatum, die bei Šulgi-simtī in

verschiedenen kultischen Kontexten beopfert wird, stammt ebenfalls aus der

Gegend von Ešnunna, aus Zimudar. Auch Annunītum und die ihr verbundene

Ulmašītum, die Annunītum ihres Tempels É-Ulmaš in Akkade, gehören zu den

bevorzugten Göttinnen der Königin. Annunītum war eine Ištargestalt mit dem

Aspekt der kriegerischen Göttin. Ihr Kult war seit der Akkadezeit für die

Könige von großer Bedeutung. Eine weitere dem Kreis der Inanna

nahestehende und von der Königin verehrte Göttin war Nanaja, wie Inanna eine

Tochter des Himmelsgottes An. Des weiteren sind die Liebesgöttin Išḫara und

die Gottheit Allagula zu nennen. Bei letzterer ist nicht einmal bekannt, ob es

sich um eine Göttin oder einen Gott handelt.

Regelmäßig wurde die Göttin Ninsun, nach der Königsideologie die

göttliche Mutter der Könige von Ur, von Šulgi-simtī mit Opfern bedacht.

Dagegen findet Lugalbanda, der göttliche Vater der Könige, keine Erwähnung

in den Texten der Königin. Der König versorgte seinerseits beide göttlichen

Elternteile mit Opfergaben. Auffallend selten erhielt Ningal, die Gemahlin

des Mondgottes, Opfer von der Königin, allerdings ist diese Göttin im Kult des

Reiches von Ur eher von untergeordneter Bedeutung.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on May 3, 2016 17:26:16 GMT -5

From RIA9 p.319, Entry by A. Cavigneaux and M. Krebernik dNimintaba      d dNimin min-tab-ba,      older writing dNin-min-tab-ba (in the old babylonian An=Anum forerunner TCL15), wife of Kalkal, doorkeeper of Enlil, or his temple Ekur In An=Anum IV Nimintaba appears as one of 4 ddigir-gub-ba (Wächtergottheiten/Guardian Gods) of Sin. One of her temples, built by Shulgi, was excavated in Ur. Her name means "Double-Fourty", wich is probably a mathematical play on words. Etymological dNin-min-tab-ba, "Lady of the two apposed" is the source. Lambert interprets the name in a cosmic sense, giving it the meaning "She who holds the universe". According to her function her name correlates more likely to the closing of doors (doorkepper divinities) |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jul 31, 2016 13:53:25 GMT -5

From: The Sumerian goddess Inanna (3400-2200 BC) by Paul Collins

Southern Mesopotamia, called Sumer, witnessed the development of the

world's oldest writing system during the Late Uruk period. However, there are

few references to Inanna in the extant cuneiform records before the Dynasty of

Akkad. Any reconstruction of the cult of Inanna at the dawn of history must,

therefore, rely initially on textual evidence of much later periods: the vast

repertoire of myths, hymns and prayers to the goddess have been attributed to the

3rd Dynasty of Ur III and the Isin-Larsa Dynasties. Certain details in

these stories may reflect beliefs and practices from earlier periods but, these

elements are difficult to identify. However, the archaeological record of the late

fourth and third millennia has revealed evidence for numerous temples dedicated

to Inanna, testifying to an important and widespread cult.

...

The temples of Inanna

Adab (Tell Bismayah)

Among the temples abandoned by Inanna in the Sumerian text of the 'Descent

to the Underworld' (Kramer 1951), is the 'Eshar' of Adab. A number of

inscriptions referring to this temple were recovered from a temple building on

Mound V, including a text of Mesalim (c. 2550 BC). None of these inscriptions

mentions Inanna. Three brick stamps were discovered on mound IVa, describing

the fourth king of the Dynasty of Akkad, Naram-Sin, as 'the builder of the temple

of the Goddess Inanna' (Banks 1912: 342). No temple was located on this mound

and the inscriptions may possibly refer to the building on Mound V at which a

deep sounding suggested a long sequence of buildings dating from ED IIII

(Banks 1912: 322).

Bad-tibira (Tell al-Mada'in)

No temple building is known, but an inscription of Entemena (c.2404-2375)

found at the site records the building of the E-mush temple, dedicated to Inanna

and Dumuzi. The temple is listed among those abandoned by the goddess in

Inanna's Descent (Kramer 1951).

Eresh(?) (Tell Abu Salabikh)

Among the texts recovered are the ZA.M! hymns (c.2500 BC), forerunners of

later temple hymns of Enheduanna......

These take the form of a list of prayers addressed to specific temples throughout

the southern Mesopotamian plain, including the temples of Inanna in Kullaba

and Zabalam, and the temple of 'Inanna of the mountain' (Biggs 1971: 45-56).

A fragmentary god list from the site reveals Inanna as the sixth deity after Anu,

Enlil, Nin.KID, Enki and SES.KI (Biggs 1974: 83).

Girsu (Telloh)

Although there is no evidence for temple buildings, it has been suggested that the

ED II 'Construction Inferieure' had a religious function (Crawford 1987: 72).

ED III texts from Girsu mention an 'Eb temple of Inanna' within an area called

Eanna. The term Eanna presumably refers to a temple complex such as those at

Uruk and Lagash. It is significant that the cities of Girsu and Lagash, which were

part of a single kingdom during ED III, both have temples called Ib (Eb)

dedicated to Inanna. The etymology of the name Ib remains unclear.

Kish (Tell lngharra/Tell Uhaimir)

The remains of a Neo-Babylonian (612 - 539 BC) temple at Ingharra is assumed

to be the last version of a building which 'was in the early periods dedicated to

Inanna' (Gibson 1972: 4). Texts of the 3rd Dynasty of Ur list Zababa and lnanna

as the deities of Kish. In the story of Inanna's Descent (Kramer 1951), the temple

of Inanna at Kish is named as Hursagkalamma.

Lagash (Al-Hiba)

A temple with an outer oval shaped court which was surrounded by a wall is

identified as the 'Ibgal of Inanna', based on 14 inscribed foundation figurines

found in situ. A foundation stone of Enannatum I (EO Ill), and votive bowls, all

dedicated to Inanna, were found in the level 11 fill. The temple levels are dated

by the excavator to late EO Ill, and a sounding beneath Level III revealed eight

earlier architectural levels, with the lowest producing spouted jars and cups dated

to EO I (Hansen 1980: 424).

Nippur (Nuffar)

Here, 27 levels of a temple dedicated to Inanna, identified initially on foundation

deposits of Shulgi (c.2094 - 2047 BC) in the uppermost level, have been

uncovered. The building is called E-duranki in Shulgi's foundation texts, but in

'Inanna's Descent' it is named as Baradurgarra (Kramer 1951). The best

preserved buildings of the lnanna temple sequence are the ED II and ED III

structures. The plans of these two temples are essentially the same with the later

building wider and longer. In each, there are two sanctuaries, paralleling the Late

Uruk Inanna temple depicted on the Warka vase relief. On clearing the floor of

the level VII temple, the excavators discovered over fifty stone bowls and statues

(Crawford 1959; Hansen and Dales 1962). Approximately forty of these objects

were inscribed, and are dedicated, mainly by women, to Inanna.

Shuruppak (Tell Fara)

Many administrative and lexical tablets were recovered from the site dated to

c.2500 BC and are the direct descendants in content of many of the earlier Uruk

tablets. The god lists from Shuruppak name Inanna as the third deity, coming

after Anu and Enlil, but before Enki. It is not known whether these tablets were

the records of a temple, or a palace, or come from various buildings. A possible

temple has been reconstructed by Martin (1975) but it is not known to which deity

it was dedicated.

Ur (Tell al Muqayyar)

It is assumed that a major Earl Dynastic building lies buried within the ziggurat

of Ur-Nammu. There is evidence in the form of a list of offerings, dated to ED

III, recovered from the site that Inanna and Nanna (the moon god and patron deity

of Ur) were considered to be the chief gods of Ur at this time (Alberti 1986: 104).

The later hymns of Enheduanna confirm the importance of Inanna at Ur ...

Uruk (Warka): Eanna

The rulers of the Dynasties of Ur III and Isin/Larsa appear to have had a strong

predilection for the religious and literary traditions of Uruk, and their inscriptions

and building activity at Uruk identify the site of a major temple complex connected

with a cult of Inanna, called Eanna, 'the house of heaven'. However, the earliest

surviving reference to this precinct is in an inscription of Lugalkingeneshdudu, king

of Uruk (c.2400 BC). The inscription occurs on a stone vase dedicated at Nippur

to lnanna of Eanna. Unfortunately, the identification of an lnanna temple within the

Eanna precinct has been frustrated by the lack of any relevant objects found in

context. The various complex building phases muddle the issue further. It is

possible that the main Inanna temples lie buried beneath the 3rd Dynasty of Ur

ziggurat of Inanna to the north-east of the Late Uruk complex of buildings.

However, the importance of the goddess in the late fourth millennium at Uruk can

perhaps be inferred from the the number and range of objects associated with

Inanna, including sculpture, seals and sealings, and cuneiform tablets.....

Uruk: Kullaba

It has been suggested that the city of Uruk grew out of two settlements, Kullaba

and Eanna which by the beginning of the third millennium BC formed one unit

surrounded by a city wall (Nissen 1972). Certainly the concept of twin areas of

the city survived into the historic period. An inscription of Utu-hegel (2019 -

2013 BC), for example, refers to 'the citizens of Uruk and the citizens of Kullaba'

(after Sollberger and Kupper 1971: l31). The area identified at Uruk as Kullaba

(about 500 m west of the Eanna precinct) contains the remains of a series of

temples set on terraces dating back to the Ubaid period. The earliest reference

to Kullaba is in the ZA.MI hymns from Abu Salabikh (c. 2500 BC) where Uruk

is called the 'twin brother of KuIlaba' (Biggs 1974: 46), and praise is addressed

to the Temple of Inanna of Kullaba. There is no mention of the Eanna complex

in the ZA.MI hymns, whereas in the later temple hymns, Eanna is described as

the 'house with the great me (duties and standards) of Kullaba' (Sjoberg and

Bergmann 1969: 29). This suggests that in the third millennium the term Kullaba

encompassed the whole religious area of Uruk including Eanna, rather than one

single temple complex. Utu-hegal' s division of the city thus makes a distinction

between the population of the religious sector and the inhabitants of 'secular'

Uruk.

Zabalam (Ibzaykh)

The earliest connection of Inanna with Zabalam is found on Archaic Level III

tablets from Uruk, where MUS-te (MUS being a reading of the Inanna symbol...)

is interpreted as the city (Green and Nissen 1987:248).

Some four hundred years later, the ZA.MI hymns from Abu Salabikh give

praise to the Zabalam temple of Inanna (Biggs 1974:53). The temple hymns of

Enheduanna also address praise to 'the house of Inanna in Zabalam' (Sjoberg and

Bergmann 1969: 36). The temple is called Giguna in the myth of Inanna's

Descent (Kramer 1951).

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jul 31, 2016 18:51:27 GMT -5

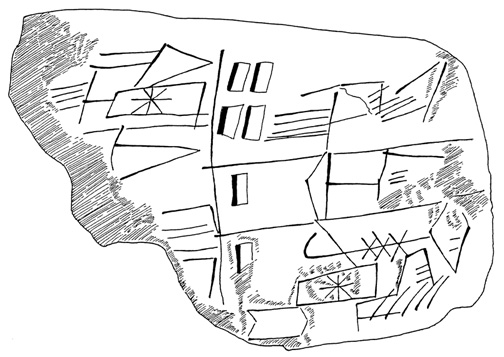

From: The Sumerian goddess Inanna (3400-2200 BC) by Paul Collins

The symbol of Inanna

The earliest references to the name Inanna are on clay tablets from the Eanna

district of Uruk; in levels below the remains of major religious buildings dating

to the 3rd Dynasty of Ur, and termed 'Archaic' by the excavators.

.....

The level IV tablets (c. 3200 BC) contain signs which are purely pictographic

and among these occurs a symbol which has been identified in texts of a later date

as INANNA or MUS ('radiant' - perhaps a description of Inanna) (Falkenstein

1936; Green and Nissen 1987). On the Uruk III tablets (c. 3100-3000 BC) the

signs have become more abstract in form, and are much closer to the fully

cuneiform shapes of later periods. These tablets can now be read with some

confidence, as the language is recognisably Sumerian. One contains a geographical

list mentioning d.inanna.ki (the place of Inanna), perhaps to be identified with

Eanna,and MUS-te, possibly the town of Zabalam (Green and Nissen 1987: 248).

Andrae (1930) has suggested that the Inanna symbol represented a support

for the entrance and door of a reedhouse such as those built in the southern

marshes of Iraq today. The upper ends of the reed bundle are bent over to form

a loop 'through which to slip a pole supporting the reed mat which formed the

door, and with the surplus ends of the reeds left sticking out at the back, thus

forming the "streamer'" (van Buren 1945: 48).

.....

The meaning of the lnanna signappears to have been lost by ED II,

as it then disappears from the artistic repertoire, perhaps reflecting

a decline in Eanna's importance as other cities

established their own Inanna cults and political independence.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Jul 31, 2016 19:22:21 GMT -5

From: The Sumerian goddess Inanna (3400-2200 BC) by Paul Collins

Conclusion

The complex character of Inanna/Ishtar that emerges from representations and

literary texts probably represents an assimilation of the functions of numerous,

often provincial, female deities as well as the more obvious roles of Inanna and

Ishtar during the third millennium BC. The tradition of Inanna/Ishtar as a goddess

of love and war thus presented a portrait of the goddess 'as the independent,

wilful, and spoiled young noblewoman whose seductive and voluptuous charm

hides a fickle heart and a vicious temper' (Roberts 19]2: 40). As such, Inanna

formed a character of such complexity and adaptability that she was highly

attractive to poets and story-tellers, ensuring her survival as an important deity

throughout ancient Mesopotamian history.

|

|

|

|

Post by hukkana on Aug 3, 2016 17:50:21 GMT -5

So, the question is, what about the lesser deities of Mari and Ebla ? Because I believe especially the latter has many deities reffered to in summary which don't get mentioned in many easily accessible texts.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 9, 2016 14:05:58 GMT -5

A little bit more on dream gods

From: Dreams as gods and gods in dreams by Annette Zgoll;

in: Cuneiform Monographs 46, He Has Opened Nisaba’s House of Learning,

Studies in Honor of Åke Waldemar Sjöberg on the

Occasion of His 89th Birthday on August 1st 2013

A number of deities “specialise” in conveying dreams. These are the dream

gods. They are known under different names. One is in Sumerian simply

called dMamud, “Dream (deity)”. But there is an interesting detail to

note. Sumerian has two words for “dream”: ma-mu(2).d and maš(2)-gi6.k.

Of these two, only ma-mu(2).d can be written with the divine determinative

digir (d), i.e. a sign which indicates that the so-marked word is

the name of a deity. As well as being the name of the dream deities, the

word ma-mu(2).d also denotes a meaningful dream which has the power

to influence the future, while the other word, maš(2)-gi6.k, refers to all

types of dreams, including confused, false, and incomprehen-sible ones. A

comparison of the different uses of the two Sumerian words for “dream”

thus yields an interesting result: a clear and unambiguous pattern that

usefully underscores the connection between one of these words and the

realm of the gods.

The word dMamud, which signifies “Dream (deity)”, is listed in the

divine genealogies (LL) as the daughter of the Sun God. Since dreams

usually occur at night, the close genealogical connection between the god

of dreams and the Sun God may seem puzzling. The riddle may be solved,

however, by considering that dreamers see a world which is just as bright

as the day.

Dreams are spaces for experiences, in which a human can be visited by

either the highest deities, or one of their messengers, such as the minor

astral or dream gods. In this respect, these sources also preserve signs of

a certain diachronic development. The later the text, the more likely it is

that a dream mediator will be used to mediate between the higher gods

and human beings.

...

There is, however, evidence that a central

concept in their understanding of what it meant to be human was

the idea of a “spirit” of breath or air, called zaqīqu. It is conceivable that

this breath could also emanate from a human being and be transferred

to other spaces. In this way it was possible for a dreamer, by means of

his zaqīqu, to be at another place during a dream and to encounter not

only divine entities, but also other human beings. This is certainly how we

should understand the “spirit”, or zaqīqu, of a person being able to come

into contact with the zaqīqu of another person.

...

It is interesting that “zaqīqu-spirits” are attested not only for humans,

but also for deities. In this respect, the deified “zaqīqu-spirit” is a manifestation

of a dream god, Sumerian Sisig, which, like the goddess dMamud,

was considered to be a child of the Sun God.

zaqīqu-spirits were conceptualised as parts of humans as well as deities

that were active precisely during the course of dreams. In this respect

they can be characterized as “dream-spirits”, in contrast to the eṭemmu-

“spirit”, which sometimes refers more specifically to the “Spirit of the

Dead”.

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 11, 2016 19:43:44 GMT -5

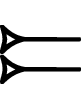

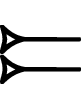

On my cdli travels i found a god i had never heard of before, Ninagala ( DNIN.A 2.GAL). First i thought it is a form if Ninegal, but no... from RIA9 translated by me      Nin-agala ( dNin-a 2-gal) Lord of the great arm, a smithing god, In An = Anum-predecessor CT 15, 10: 470 and in An = Anum II 346 f. (Litke, God-Lists 128) he follows the fire god, later, like many other crafting gods, he was identified with Enki/Ea. Ur-Ba'u of Lagash calls himself dumu tu-da dNin-a 2-gal-ka-ke 4 "bodily son of Ninagala." (RIME 3/1, 20: 7 f.). Ninagala is mentioned in connection with the making of statues, often together with Kusigbanda ( dKUG.GI.BAN 3.DA) Nin-agala´s wife is Nin-imin. here is a nice Inscription by Ur-Ba`u CDLI Linkthe name singled out  and the whole tablet  |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 11, 2016 19:53:57 GMT -5

I also found an interesting piece of an EDI-II tablet piece from Ur with an entry for AMA-KI-EN-GI. I wonder if it is an epiphet for a goddess. CDLI Link |

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 12, 2016 6:55:03 GMT -5

from: Born In Heaven, Made On Earth by Michael B. Dick

A mouth opening ritual for a statue, Ninagala is mentioned in this one.

Asalluhi is the Sumerian name of Marduk.

I´d like to thank Salmu for pointing this text out to me.

"The rubric emphasizes that the incantation is primarily concerned with the concept

of mouth-opening rather than mouth-washing. Given the rather subordinate status

of mouth-opening in the existing rituals, the incantation may reflect historically

earlier cultic practices. The reference to the apkallu and abriqqu points in the same

direction.

02. Incantation: On the day when the god was created (and) the pure statue was completed,

04. the god was visible in all the lands.

06. He is clothed in splendor, suited to lordliness, lordly, he is full of pride,

08. he is surrounded with radiance, he is endowed with an awesome radiance,

10. he shines out splendidly, the statue appears brilliantly.

11. In heaven he was made, on earth he was made.

13. This statue was made in the totality of heaven and earth;

15. this statue grew up in the forest of hashurru-trees;

17. this statue came from the mountains, the pure place.

19. The statue is the creation of (both) god and human!

21. [The statue] has eyes which Ninkurru made;

23. [the statue has . . . ] which Ninagal made,

25. the statue is of a form (bunnannû) which Ninzadim made,

27. the statue is of gold and silver which Kusibanda made,

28. [the statue . . . . . .] which Ninildu made,

30. [the statue. . . . . which] Ninzadim made.

32. This statue which [is made of ] hulalu-stone, hulal-ini-stone, mussaru-stone,

Lines 34 to 36 are broken; however they refer to the different semi-precious stones

(pappardilû-stone, elmesu-stone, antasurrû-stone) from which the statue was made.

38. By the craft of the qurqurru-craftsman

40. this statue Ninkurra, Ninagal, [Kusibanda], Ninildu (and) Ninzadim

[made].

43. This statue without its mouth opened cannot smell incense, cannot eat food,

44. nor drink water.

45. Asalluhi saw this (and repeated it) to his father Enki (in the Apsu),

46. “My Father, this statue without its mouth opened (cannot smell incense,

cannot eat food, cannot drink water; show me what to do).”

47. Enki (answered) his son Asalluhi: “My son, what do you not know? (What

can I tell you?)

48. Asalluhi, what do you not know? (What can I tell you?) Whatever I know

(you also know). Go, my son!

50. Waters of the Apsu fetched from the midst of Eridu,

52. waters of the Tigris and Euphrates . . . from a pure place,

54. tamarisk, mastakal, heart of date-palm, salalu-reed, multi-colored marshreed,

56. seven palm-shoots, juniper, white cedar throw into it.

58. In the garden at the pure canal of the orchard construct a “House of

Washing (bit rimki ).”

60. Bring him (the statue) out to the “House of Washing” at the pure canal of

the orchard.

62. Bring this statue out before Shamash.

64. The axe that touched him, the hatchet that touched him, the saw that

touched him, and the craftsmen (marê ummâni ) who touched him you

[. . .] there.

67. Bind their hands with bandages.

69. With a tamarisk sword cut off the fists of the qurqurru-workers who touched

him.”

71. This statue that the gods Ninkurra, Ninagal, Kusibanda, Ninildu, and

Ninzadim have made,

74. Kusu, the chief exorcist of Enlil, with the holy-water basin, the censer, the

cultic torch and with clean hands has purified.

76. Asalluhi, the son of Eridu, has made brilliant.

78–80. The wise man (and) the abriqqu-priest of Eridu with honey, butter, cedar,

and cypress have opened your mouth twice seven times.

81. May this god become pure like heaven, clean like earth, as brilliant as the

center of heaven. Let the evil tongue stand aside.

incantation—ßu-illa prayer for the opening of the mouth of a god

83. When you have recited this, you pour a libation for Ea, Shamash, and

Asalluhi.

84. You prostrate yourself and recite three times the incantation, “Pure statue

suited to great divine attributes.”102 Purifying and whispering."

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 12, 2016 15:00:53 GMT -5

From: Gods in Dwellings, Temples and Divine Presence in the Ancient Near East by Michael B. Hundley

Anthropomorphically understood divine personages manifested themselves

in and were in charge of such visible and tangible elements as celestial bodies,

natural phenomena, qualities, and perhaps more distantly numbers, stones, and

metals. For example, Ishtar was simultaneously identified as a divine person who

dwelled in heaven, yet was localized in various terrestrial temples (most prominently

Arbela and Nineveh); identified with the planet Venus, the number 15, the

semiprecious stone lapis lazuli, and the mineral lead; and understood as the embodiment

of such qualities as love and war.

The exact relationship between elements was not always clear or consistently

articulated. However, on the whole, the data seems to suggest that all of these elements

were substantially connected, such that together they constituted the deity

in all its plenitude, and in some measure each individual element partook of the

divine essence enough to be called by the divine name and associated with the

primarily anthropomorphically conceived divine personage. However, each element

was in various contexts treated as distinct, such that, for example, Ishtar of

Arbela and Ishtar of Nineveh, Ishtar of mythology and Ishtar as Venus, were not

coterminous and in many ways were understood as distinct entities. For example,

a hymn of Assurbanipal addresses the distinct Ishtars of Nineveh and Arbela,

while the treaty between the Assyrian king Esarhaddon and Ramataya, king of

Urakazabanu, includes in the witness list Ishtar of Arbela, Ishtar of Nineveh, and

the planet Venus, often associated with Ishtar, and in divine curses invokes Venus

alongside Ishtar Lady of Battle, Ishtar who resides in Arbela, Ishtar of […], and

Ishtar [… of] Carchemish. In the Assyrian tākultu ritual texts, various Ishtars in

the form of cult images are venerated separately, including an unmodified Ishtar,

Ishtar of the Šibirri Staff, Ishtar of the Stars, Assur-Ishtar, Ishtar the Panther, and

Lady of Nineveh.

|

|

|

|

Post by hukkana on Aug 13, 2016 8:24:05 GMT -5

I seem to have run across Ninagala somewhat earlier when I was going through RA. I found a mention of the God in "Erra and Ishum" (the Foster translation), the line being

"Where is Ninagal, wielder of the upper and lower millstone"

"Who grinds up hard copper like hide and who forges tools?"

|

|

|

|

Post by sheshki on Aug 29, 2017 17:59:20 GMT -5

From: Altakkadisches Elementarbuch, F. Breyer, 2014

page 58

Nach Ausweis von präsargonischen Namen war der akkadische Sonnengott

ursprünglich weiblich und wurde wohl erst durch die Synkretisierung mit dem sumerischen Utu männlich.

Which loosely translates into: According the Pre-Sargonic PN´s the Akkadian sungod was female

and only through syncretisation with the Sumerian Utu he became male.

|

|